Making migration safe

On Tuesday, countries from across the world met in Marrakesh to adopt the Global Compact for Safe and Orderly Migration, whose text was agreed this summer, and published on World Population Day, 11th of July. Our Head of Campaigns and Communications, Alistair Currie, examines its provisions, and asks if it goes far enough.

The crisis

The stimulus for the Global Compact (GCM) was the humanitarian migration and refugee crisis of 2015, which saw hundreds of thousands of people risk, and sometimes lose, their lives trying to cross the Mediterranean by boat in order to live in Europe. That crisis has not ended, of course. Factors from climate change and conflict to a desire for better material circumstances are driving the mass transnational movement of people as never before. According to a new Gallup poll, more than 750m people want to live in another country permanently – more people than before 2015.

In addition to the immense suffering and loss of life of those migrants, countries such as Greece and Italy have struggled to cope with the number of migrants and refugees reaching their shores. For millions of people, migration is “safe and orderly” – but as the crisis showed, for millions more, it has been the polar opposite – and migration pressures threaten to make that worse.

Responding to the challenge

Based on the principle that a multilateral approach is essential, the GCM is intended to offer a set of common rules and principles to guide the national and international response. (Note – the GCM concerns migrants, a separate compact will address refugees.) In the words of Miroslav Lajčák, the President of the United Nations General Assembly, the Global Compact’s potential is to “guide us from a reactive to a proactive mode. It can help us to draw out the benefits of migration, and mitigate the risks.” To an extent, this is true – but while the compact provides a step forward in respecting the rights and dignity of migrants, it also fails to address potentially serious harmful impacts of the mass movement of people in the 21st Century.

The agreement was the product of extensive negotiation between governments, accommodating widely differing perspectives, needs and concerns. At the end of that process, every country but one had agreed to the compact, the exception being the United States of America. However, at the Marrakesh meeting, a number of others joined the US in refusing to adopt it, including Hungary, Austria, Australia, Poland and Italy. Brazil will withdraw when its new far-right president-elect, Jair Bolsonaro, takes office next year.

A common theme in these objections is that the compact prevents countries managing immigration. In fact, the GCM is non-binding, and does not place any obligations on countries in regard to how many people they permit to enter and live in their countries, or their criteria for determining who (as long as human rights and existing legal obligations are respected). The UN Special Representative for International Migration, Louise Arbour sums up the policy as, “preserving the states’ sovereignty and their right to decide their migration policies.”

Protecting people

Population Matters strongly welcomes the adoption of a system that attempts to protect people’s human rights, ensure their safety, and provide a rational structure for managing a phenomenon which is often chaotic, unstructured and harmful to individuals and communities. No one should drown in pursuit of a better life, no one should face life in a new country as a wage slave propping up the profits of businesses seeking the cheapest labour, and no local community should be overwhelmed by migrants or refugees they haven’t the resources or infrastructure to accommodate.

Nor should anyone feel their home is somewhere they cannot stay. We especially welcome the compact’s focus on the drivers of migration. Population Matters has long advocated for trade and aid policies which reduce global inequalities and prioritise development, opportunity and stability where people are. Such policies – which are, of course, the right thing to do anyway – would also undoubtedly massively reduce that figure of three-quarters of a billion people seeking to move.

The compact states:

“We commit to create conducive political, economic, social and environmental conditions for people to lead peaceful, productive and sustainable lives in their own country and to fulfil their personal aspirations, while ensuring that desperation and deteriorating environments do not compel them to seek a livelihood elsewhere through irregular migration.”

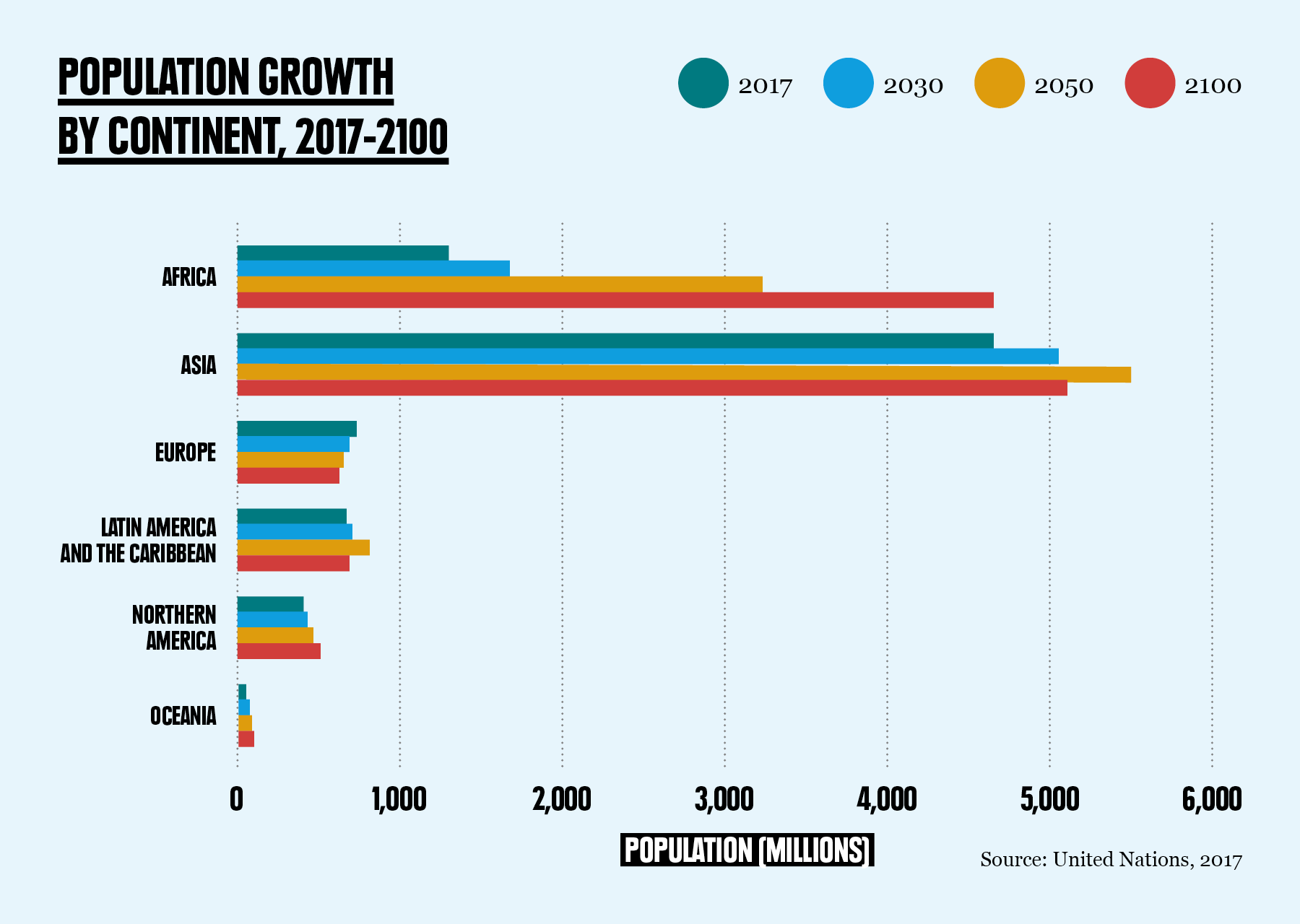

Very many of the drivers of migration are related to population. Resource scarcity, unemployment, price rises, land degradation and more. High population growth frequently stalls economic development, and most often in countries with a large population of young people, who see no hope of achieving the quality of life they aspire to where they are.

Many of these drivers will be made worse by our environmental crisis, especially climate change. Countries deprived of usable and productive land will face greater population pressure on their resources and economies. Armed conflict – both within and between states – over resources or because of the pressures arising from their shortage will be one consequence, creating more migrants and refugees. Climate change – driven by wealthy countries – takes its toll first in places where people are poor.

Migration and the Environment

Critically, however, the compact fails to recognise that the mass global movement of people threatens not just short-term humanitarian or political crises. Migration isn’t just a response to environmental problems, it can also contribute to them. Expanding populations in those rich countries driving climate change will make it worse, hitting especially many of the poor countries migrants want to escape. While migration can offer refuge, it could contribute to a vicious cycle of worsening environmental problems driving ever more people to leave. Attempting to address migration drivers without taking this into account cannot ultimately succeed.

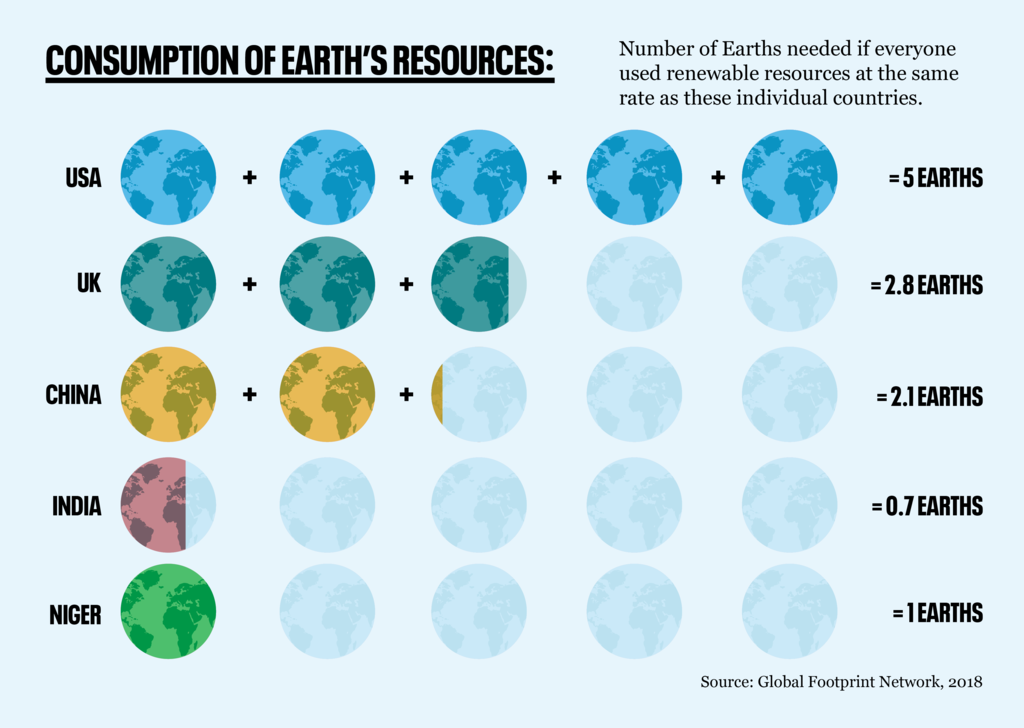

People very often move to improve their material circumstances – from rich countries to richer ones, from poor countries to less poor ones, or from poor countries to rich ones. While emigration can help to relieve local environmental pressures in many circumstances, those people will almost always increase their environmental footprint – their consumption, their waste and their carbon emissions (of course, many migrants remain poor by the standards of their destination countries once they arrive, and their environmental impacts are frequently below the average for those nations). If everyone lived as average Americans do, for instance, we would need five Earths to meet their needs. Therefore, the more people move to the US, the greater the stresses on our planet become – and the Gallup poll shows that 158m want to do so. We must not close the doors on everyone seeking a better life through voluntary migration – it’s a right many of our ancestors took up and the reason many of us enjoy the privileged lives we do. But nor can we ignore that what counts as a better material life for an individual (whether someone born to it or migrating towards it), may not mean a better life for everyone else.

Too many people living in unsustainable affluence are at the heart of our problem. We need a system which recognises that the untrammelled consumption and environmental recklessness of the rich world cannot continue, meaning those of us who live there now need to radically change the way we live. Those of us who already live more affluent lives must recognise that our analysis comes from a position of privilege. From colonialism to consumerism, the current and historical actions of ourselves and our nations are among the reasons that others live with poverty or conflict. That does not alter the fact, however, that making more people affluent by translocating them in their hundreds of millions from poverty to the same unsustainable lifestyles already enjoyed by far too many would spell disaster. Navigating the moral complexities arising from that situation is our challenge.

Global inequality is a profound injustice, and no one deserves to be condemned to poverty or danger because of where they happen to be born. We cannot and must not resist climate change by keeping people poor, and we must recognise the role and value of migration in transferring wealth from rich to poor countries, in the form of remittances or returning migrants. At the same time, emigration can – and does – drain countries of skilled and productive young people. It is no panacea for poverty.

The challenge of immigration

Nor are migration’s downsides confined to its environmental impacts or effects in origin countries. The concerns of people in destination countries should never be dismissed as simply selfish, xenophobic or trivial. Preserving, or achieving, a decent quality of life for everyone within a nation-state is impossible if population is too high and/or growth too rapid. Infrastructure, public services and the environment rarely keep pace with the needs of a rapidly expanding population.

Of course, population is far from the only factor affecting those variables – with fiscal and political policies capable of exacerbating or mitigating those challenges. Nevertheless, while treasuries, neoliberal economists and multinationals see immigration as a source of tax revenue, cheap labour and more consumers, the citizens of many countries recognise the threats to their quality of life posed by population growth. This concern is not confined to rich countries. It applies within countries when people move from rural to urban lives, for instance, and in nations of the Global South which are likely to see increasing migration from neighbouring countries as a result of climate change and other pressures.

Unquestionably, some people’s sense that their concerns are ignored has also been exploited by and contributed to a rising tide of right-wing, populist political parties and leaders, whose rhetoric, nationalistic agendas, attacks on experts and contempt for environmental protection pose a grave threat to sustainability and global justice.

Past, present and future

Migration lies at the heart of the story of humanity. It has enriched cultures, economies and individual people’s lives for millennia, though it has also brought destruction and exploitation to indigenous peoples and the natural world for millennia. It would be a grave mistake to see it as universally benign. Whatever its past, we must face with realism its present and future. Three-quarters of a billion people seeking to move is an unparalleled number – and in the 21st Century, migration carries dangers and implications for our collective future that it never has before. These are risks that we ignore, literally, at our peril.

The days of impervious national borders and homogenous national populations are over, and rightly so, and our obligations to asylum seekers and refugees are absolute. Climate change and global injustice will mean more voluntary migration (and, tragically, more refugees) in this century and it is essential that it is managed rationally, humanely and in recognition that doing so is a shared global responsibility. The GCM represents a very significant step towards achieving that, but a really comprehensive global migration framework would help manage it in a way that benefitted people, countries and economies in a truly sustainable way. The GCM fails that test.

Trying to tackle global migration without tackling the global population is, however well-meaning, an act of blindness. What is needed is a multilateral agreement to address the overarching problem – a growing, already unsustainable global population. Population Matters strongly supports such an international framework, and right now is examining the options and possibilities for how it can be achieved.

Averting environmental catastrophes and ensuring enough of the world’s resources for everyone, now and in the future, are absent from the Global Compact for Safe and Orderly Migration. In the time of the Sixth Mass Extinction and with just 12 years to stop devastating climate change, that is an omission that threatens everyone’s safety.