Lowering infant mortality will lower population growth

A new paper published by a group of Australian academics has established that reducing infant mortality rates will lower global population growth. Their conclusion: improved access to contraception and family planning is what’s required.

A comprehensive study published in Plos One last month has shown a direct link between keeping babies alive and reductions in global population. Although this may at first seem counterintuitive, the research found strong evidence to confirm the theory that the more babies a woman loses, the more she is likely to have.

“While many studies have reported relationships between availability/quality of contraception and family planning, infant mortality, and fertility, these relationships have not been evaluated quantitatively across a broad range of low- and middle-income countries.”

Globally, around one out of every fifty babies born does not survive its first year, but as many as one in twelve may not survive in the worst affected countries – all of which are in Africa. Around 2 million babies die each year globally in the first month of life.

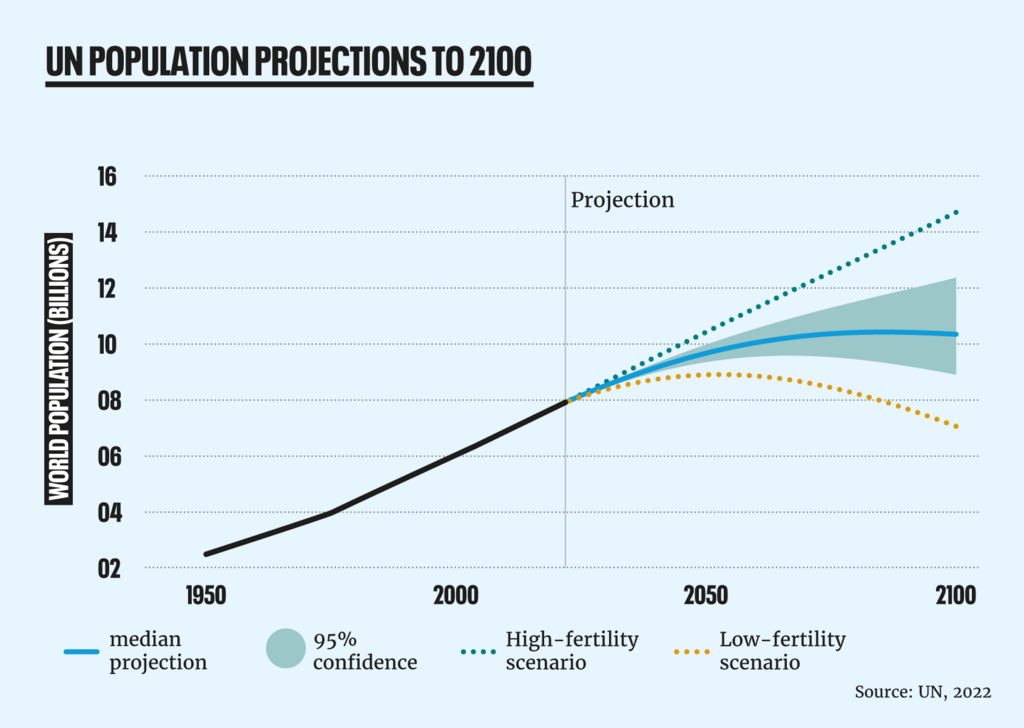

Lower infant mortality, lower household size, and more access to contraception reduce fertility in low- and middle-income nations (incorrectly titled …higher household size on Plos One) is published when the world has recently passed the landmark birth of the 8 billionth human being. The United Nation’s (UN) median projections suggest that the world’s population will be 9.7 million in 2050 and will peak at 10.4 billion in 2080, meaning 2.4 billion more people in the next 57 years. There is certainly no room for complacency, the UN’s high-fertility projection has us at a frankly terrifying 14.8 billion people by the end of the century, an increase of 6.8 billion in fewer than 80 years.

THE ‘INSURANCE EFFECT’

Whilst it seems illogical, that higher infant mortality leads to higher population growth, that’s due to the ‘replacement’ or ‘insurance’ effect, meaning that “the more babies a woman loses, the more children she is likely to have”. The effect has an influence on culture and expectations – countries with high infant mortality tend to have a larger “desired family size”.

Access to contraception and family planning, however, pushes in the opposite direction and can help break that cycle, giving women autonomy and a chance to plan when, how often, and indeed whether, they get pregnant.

The study, carried out by six Australian academics, used publicly-available data from 64 low- and middle-income countries. They collated data across six themes; availability of family planning, quality of family planning, female education, religion, mortality and socio-economic conditions.

“Keeping babies alive actually reduced average fertility and helps put the brakes on population growth. Essentially, higher infant mortality and a larger household size increased fertility, whereas greater access to any form of contraception decreased fertility.”

Professor Corey Bradshaw*

The findings were that higher infant mortality and higher household size (an indicator of population density) actually increased fertility. Access to contraception lowers fertility, allowing women the opportunity to plan pregnancies more effectively. This brings many benefits, including delaying the age at which women and girls first become pregnant, extending the time periods between births and relieving pressure on health systems. These benefits and others reduce the number of babies who die.

Surprisingly, the study found that female education, home visits by health workers, quality of family planning services, and religious adherence had limited impacts.

The global context

The UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are 17 defined targets that aim to achieve decent lives for all on a healthy planet by 2030. Unfortunately, not enough progress has been made and it looks likely that none of them will be fully realised in the next 7 years.

SDG3 (good health and wellbeing) and SDG5 (gender equality) highlight the fundamental right to bodily autonomy and to exercise one’s right to sexual and reproductive health. The provision of contraception and family planning is essential to that.

“Our models suggest that decreasing infant mortality, ensuring sufficient housing to reduce household size, and increasing access to contraception will have the greatest effect on decreasing global fertility.”

Currently, more than 200 million women (26 per cent of women of childbearing age) cannot access modern contraception and 50 per cent of all pregnancies are unintended. Removing barriers and increasing access to family planning is an essential part of the puzzle, giving women bodily autonomy and a choice over their family size.

_________________________________________________

* Population Matters is pleased to have commissioned Professor Corey Bradshaw, along with leading paediatrician, Professor Peter Lesouef, to undertake separate, but related research, looking at the wellbeing of future generations of children in the context of different population projections and available positive interventions and policies.