The sixth mass extinction and the future of humanity

Everyone is aware of the climate crisis but not many people know there is another, equally serious environmental crisis: the sixth mass extinction. Renowned ecologist and conservationist Dr Gerardo Ceballos explains this alarmingly rapid erosion of biodiversity and why the survival of our own species depends on whether we manage to halt it.

Somewhere, sometime in late 2019, a coronavirus from a wild species, perhaps a bat or a pangolin, infected a human in China. This could have been an obscure event, lost without trace in the annals of history, as it is very likely this has occurred many times in the last centuries. But this particular event was somehow different. The coronavirus became an epidemic first and a pandemic later. Covid-19 became the worst pandemic since the Spanish flu in 1918. The horrific human suffering it has caused, and its economic, social and political impacts, are still unraveling.

The reason Covid-19 and more than forty other very dangerous viruses, such as Lassa fever, HIV and Ebola, have jumped from wild animals to humans in the last four decades is the destruction of natural environments and the trafficking and consumption of wild animals.

The wildlife trade is to satisfy the insatiable and extravagant demand for these species in the Asian market, in countries such as China, Vietnam and Indonesia. The illegal wildlife trade is a gigantic business. It is as lucrative as the drug trade, but without the legal implications. The immense appetite of China and other Asian societies for exotic animals has promoted exponential growth in trade and profits. Wild and domestic animals sold in “wet markets” are kept in unsanitary and unethical conditions. There, feces, urine and food waste from cages at the top spill into cages at the bottom, creating the perfect conditions for viruses to leap from wild animals to domestic animals and humans. Thousands of wildlife species or their products are traded annually.

Wildlife trade is one of several human impacts, including habitat loss and fragmentation, pollution, toxification and invasive species, that have caused the extinction of thousands of species and threaten many more. Indeed, most people are unaware that the current extinction crisis is unprecedented in human history. Extinction occurs when the last individual of a species dies. The UN recently estimated that one million species, such as the panda, the orangutan and the Sumatran rhino, are at risk of extinction.

The extinction crisis is more urgent than the climate crisis because it is happening extremely fast and because it is the only truly irreversible environmental problem. Once a species dies, a world is lost forever.

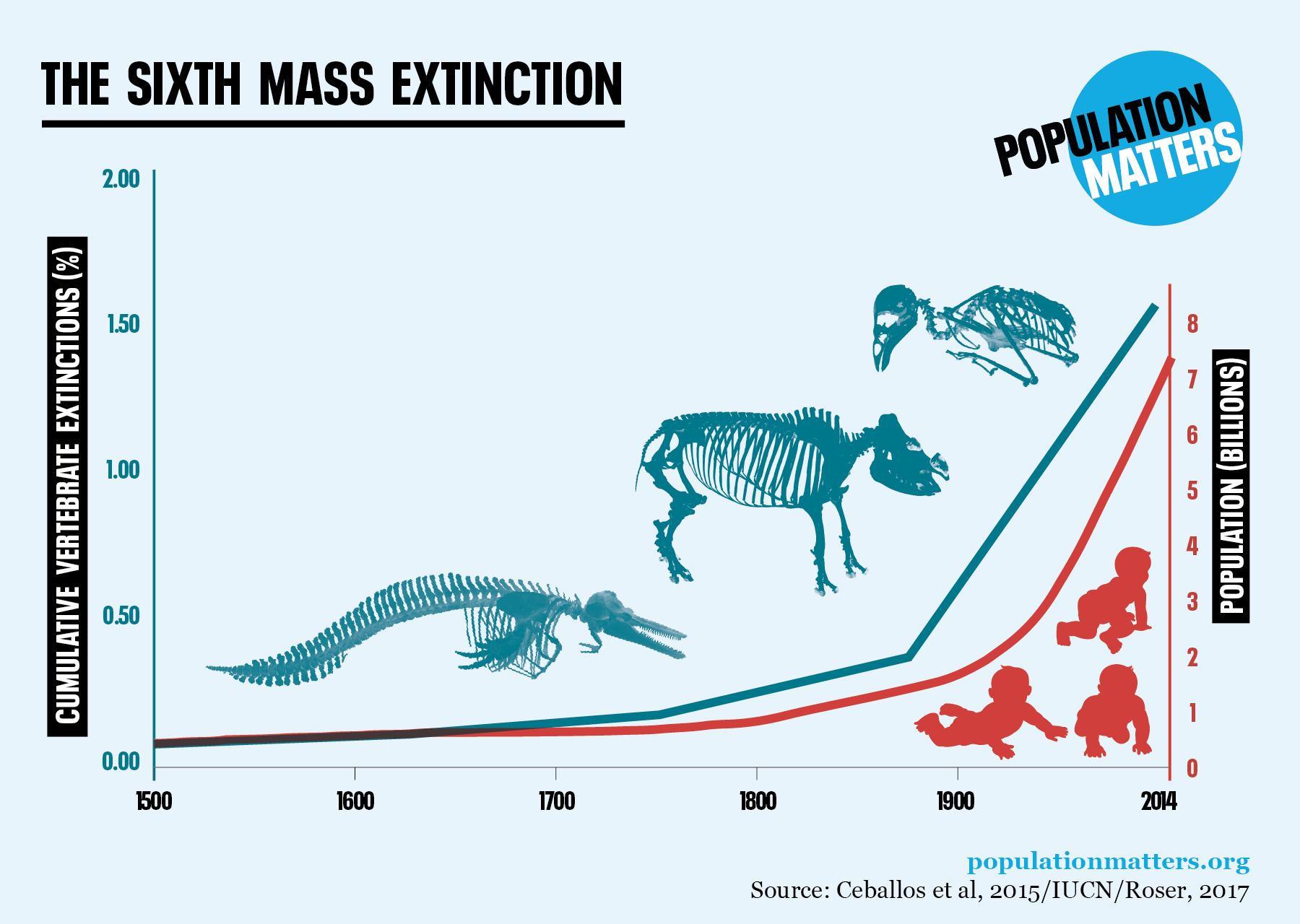

In the last five years, my scientific research has produced three major findings on the extinction crisis. First of all, we have shown that the wild vertebrates (mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians and fish) that went extinct in the last 100 years would have gone extinct in 10,000 years under normal conditions (Ceballos et al., 2015). Every year, we have lost the same number of species that would have been lost in a century! We concluded that we have entered the sixth mass extinction. A plethora of other studies on plants and invertebrates showed that the extinction crisis is happening across all kind of organisms. Five natural mass extinctions occurred in the previous 600 million years. A mass extinction is defined as the catastrophic loss of 70 percent or more of all life on Earth in a short geological time, usually tens of millions of years. The fifth mass extinction, for example, which occurred 66 million years ago, was likely caused by a meteorite impact that destroyed 95 percent of all species, including the dinosaurs.

The second finding is that population extinctions, which are the prelude to species extinctions, are occurring at very fast rates (Ceballos et al., 2017). Around 32 percent of a sample of 27,000 species have declining populations and have experienced massive geographic range contractions. Population extinctions are a very severe and widespread environmental problem which we have called “Biological Annihilation”.

Finally, our third finding indicates that the magnitude of the extinction crisis is underestimated because there are thousands of species on the brink of extinction (Ceballos et al., 2020). Those species will likely become extinct in the near future unless a massive conservation effort is launched soon.

The ultimate drivers of biotic destruction are human overpopulation, continued population growth, and overconsumption, especially by the rich. To be effective in the long-term, conservation action must tackle these root causes.

Many times, people have asked me why we should care about the loss of a species. There are ethical, moral, philosophical, religious and other reasons to be concerned. But perhaps the one that is most tangible for most people is the loss of ecosystem services, which are the benefits that humans derive from the proper function of nature. Ecosystem services include the proper mix of gases in the atmosphere that support life on Earth, the quantity and quality of water, pollination of wild crops and plants, fertilization of the soil, and protection against emerging pests and diseases, among many others. Every time a species is lost, ecosystem services are likely to erode and human well-being is reduced.

The loss of so many ecosystems and species is pushing us towards the point of collapse of civilization. The good news is that there is still time to reduce the current extinction crisis. The species and ecosystems that we manage to save in the next 10 – 15 years will define the future of biodiversity and civilization. What it is at stake is the future of mankind.

Dr Gerardo Ceballos is an ecologist and conservationist at the Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico. He is particularly recognized for his influential work on global patterns of distribution of diversity, endemism, and extinction risk in vertebrates. He is also well-known for his contribution to understanding the magnitude and impacts of the sixth mass extinction.

The views expressed in guest blog posts do not necessarily reflect the opinions and position of Population Matters.