The Sahel: Empowering women key to averting disaster

The Sahel region of Africa is on a dangerous trajectory of rapid population growth and catastrophic climate warming. Empowering women in this area is key to saving and improving countless lives. We spoke to Alisha Graves, Population Matters Expert Advisor and Founder and Executive Director of OASIS, which delivers crucial work to advance education and choice for women and girls in the Sahel.

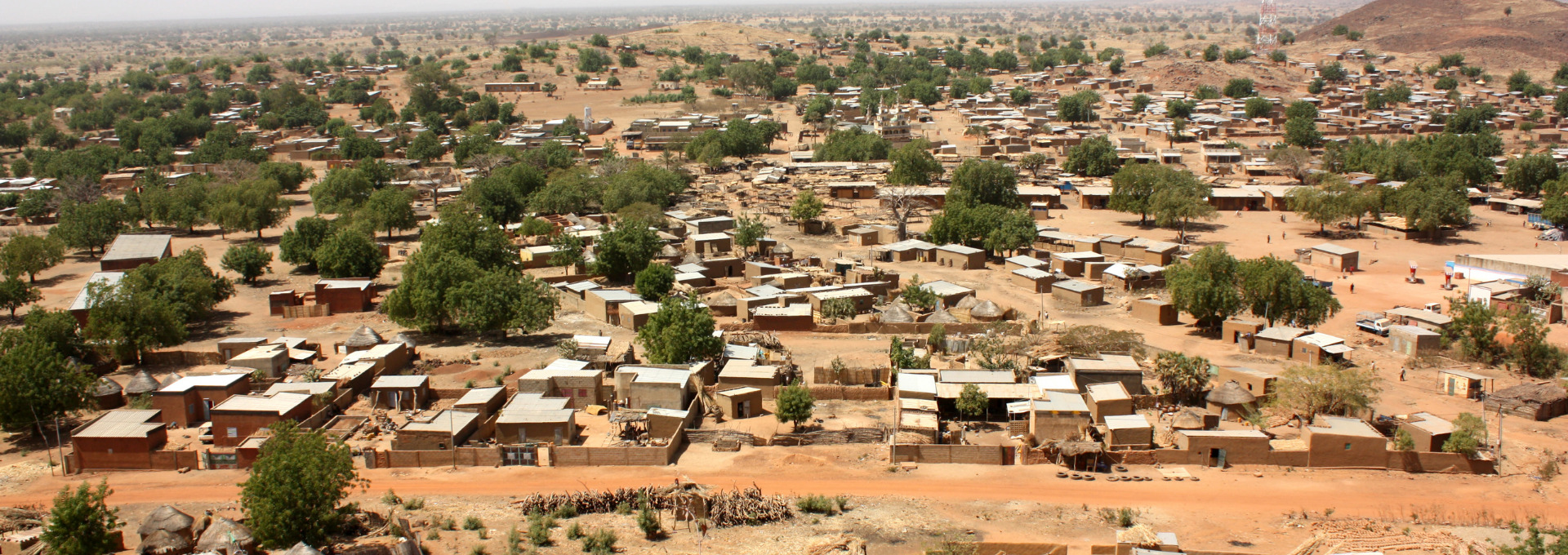

The Sahel is a geographical area spanning 5,900 km (3,670 mi) from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Red Sea in the east, between the Sahara Desert to the north and the Sudanian Savanna to the south. It stretches across northern Senegal, Mauritania, Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, northern Nigeria, Chad, and into Sudan. Women and girls in this area are among the most disempowered in the world. For example, Niger has the highest rate of child marriage out of all countries, with 75% of girls married before turning 18 and 36% before turning 15. By their 18th birthday, roughly half of all Nigerien girls have already given birth. As a result, Niger also has the highest fertility rate in the world, with an average of seven children per woman.

The Sahel’s population is projected to almost triple by the middle of the century, to 450 million people. On top of this, the region is expected to warm by 3 °C above 1950 levels, which is already negatively impacting the food and water security of the region.

Q: What are the objectives of OASIS?

A: OASIS is a non-profit organisation working to advance education and choice for women and girls in the Sahel. We’re focused on keeping girls in school, delaying marriage and overcoming barriers to family planning. Together with the Centre for Girls Education in Northern Nigeria, we’ve demonstrated that mentored girls’ clubs (safe spaces) can increase girls’ completion rates from secondary school by twenty-fold and raise the age of marriage by 2.5 years. With L’Initiative OASIS Niger, we’re building a critical mass of leaders dedicated to the education and empowerment of women and girls via the Sahel Leadership Program.

Q: What’s the prognosis for the Sahel as regards its population and climate change?

A: The population of the Sahel is expected to more than double by mid-century. Temperatures in the region are climbing faster than the global average, with a projected increase in air temperature of 2-3°C, and robust, negative effects on the staple crops. These projections, along with the low status of women, mean we must pay special attention to this region. In brief, academics and activists outside the region tend to overlook or minimise links between population and climate change. For example, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report cited family planning as being beneficial for mitigation, adaptation and health. But few of the popular press or research papers picked this up. Talking about the size of our carbon footprints without acknowledging the number of footprints is like trying to calculate the area of a rectangle using only the width. Understanding these links means we should redouble our efforts to secure rights-based family planning policies and programmes and ensure they’re available to individual women on a regional scale.

Q: You’ve also contributed to Project Drawdown, which identifies available and implementable solutions to climate change. What insights did you gain?

A: At Drawdown, we found that taken together, education and voluntary family planning are among the top solutions. By slowing population growth, there’s the potential to avert 85 gigatonnes of greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. But education without quality family planning services will be insufficient – it’s through correct information and access to contraception that a woman achieves her desired family size. More educated girls are likely to marry later, use health services, and have decision-making power. These benefits are passed on to their children in a virtuous circle.

Q: Can you elaborate on the link between education, access to family planning and adapting agricultural practices as key to confronting climate change in the Sahel?

A: These are like three legs of a stool. Without all three, the region will not be able to sustain healthy lives by mid- century. Most Sahel leaders dedicated to girls’ education and empowerment have not considered how a lack of control over fertility impedes women’s ability to take charge of other aspects of their lives. Understanding how rights-based family planning can accelerate fertility decline and make it easier to meet all of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals is creating a lot of excitement and fresh energy.

Alisha Graves MPH (Master of Public Health) co-founded OASIS and leads on its strategy, development and advocacy. She lectures internationally on population and food security in the Sahel and is a research fellow for Project Drawdown, analysing the potential contribution of family planning for reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Previously, she worked on drug registration, operations research, and advocating for evidence-based maternal health policies across seven countries in Sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia. She completed her MPH in International Maternal and Child Health at UC Berkeley in 2006. Alisha is a member of Population Matters’ Expert Advisory Group.