UK biodiversity report: more of us, less of them

The latest edition of the most authoritative report on biodiversity in the UK has just been released – State of Nature 2019. The 2016 version described the UK as “one of the most nature-depleted countries in the world”. This new edition makes clear there has been no improvement. Our Head of Campaigns, Alistair Currie, looks at the report, and what it tells us about the impact of population growth.

Scrupulously compiled by a wide range of conservation organisations, including government agencies, the State of Nature 2019 headline findings include:

- 15% of the more than 700 species assessed are threatened with extinction, including a quarter of all mammals and nearly half of all assessed birds

- Since 1970, 41% of assessed species have decreased and 26% have increased in abundance, with the remaining 33% showing little change.

- Over the past 10 years, 44% of species have decreased and 36% have increased in abundance, with 20% showing little change.

- There are some good news stories, including an increase in woodland cover and the resurgence of some previously threatened species

- As a result of habitat loss and factors such as climate change, 31% of species are now found in fewer places than they were

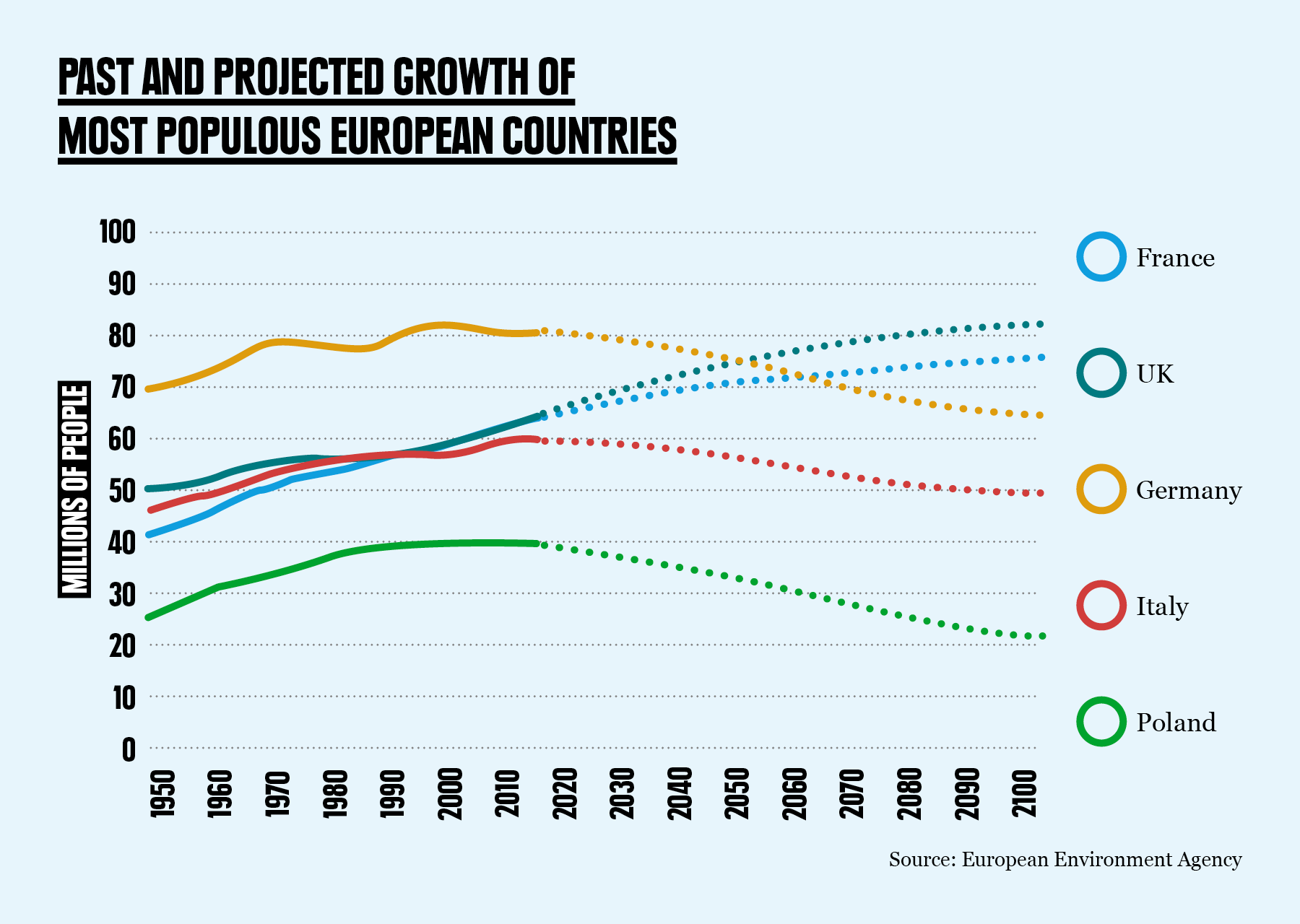

The report leaves us in no doubt that nature and the conservation community are fighting a losing battle against the UK’s ongoing assault on our wildlife. Good things are being done, but not enough. One key reason this battle is being lost is only fleetingly referenced in the report – the most rapidly expanding population of any large nation in Europe.

The areas in which the impact of population growth is mentioned are telling: water abstraction, urbanisation and infrastructure development. These developments are the inevitable consequences of population growth. We all need land, we all need water, we all need infrastructure. The report states that urbanisation accounted for a greater impact on species than any other habitat conversion and made clear one of the critical trade-offs: we can use less land if we choose to live in a Hong Kong style concrete forest of high rises, but then urban green spaces which offer vital refuges for biodiversity would be eradicated. Or if we don’t go up, we must go out, with urban sprawl outwards, grabbing up land and habitat from our countryside. While population growth is not the only factor driving increased housing demand, fewer people needing housing is a huge step towards easing that pressure.

Meanwhile, of course, population growth contributes to other drivers of biodiversity loss identified in the report, including climate change and agricultural intensification, intended to feed more people more cheaply.

The global picture

The disturbing trajectory in the UK is certainly consistent with the picture across the world – but the global situation is even worse. Numerous recent authoritative reports have detailed the gravity of the Sixth Mass Extnction and very many have clearly identified population growth as a key factor. The most significant was the global assessment of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), published in May. It explicitly identified population growth as a key indirect driver of biodiversity loss, i.e. an underlying factor which drives the processes which immediately cause biodiverity loss, such as habitat destruction and climate change. It made a very clear call:

“changes to the direct drivers of nature deterioration cannot be achieved without transformative change that simultaneously addresses the indirect drivers.”

An equally bold vision is required for the UK. The 2016 State of Nature report described the UK as one of the most “nature depleted countries in the world”. Overall, things are now worse. The causes are multiple and complex and they demand solutions which are far-reaching and substantial across a multitude of areas. The 2019 report identifies many of those, and makes clear the necessity of implementing them. It doesn’t, however, include action to address population. If we ignore the fact that the ONS projects our population will grow by more than 6 million people over the next 25 years, it’s hard to see how we can possibly expect the battle to protect our natural environment to be won.

Contact the UK government

The State of Nature 2019 report makes clear that the UK is set to miss most of the 2020 targets to protect biodiversity set by the global Convention on Biodiversity. Population Matters believes the failure of the Convention to address human population is one reason so many countries are missing their targets. Contact your government and ask them to press for that to change.