Europe’s biodiversity under pressure from growing food demand

Increasing populations lead to a subsequent increase in food demand, but how will this impact biodiversity? A recent study, published in Nature, shows the continued conversion of land to agriculture to feed growing populations in Europe will have devastating impacts on key species including wild bees, plants and earthworms. While this damage can be reduced by selecting less biodiverse areas and incorporating sustainable farming practices, limiting additional population growth is the only long-term solution for feeding everyone without destroying ever more nature.

Biodiversity contributes to the essential functioning of ecosystems, without which life on Earth would cease to exist. Across Europe, semi-natural habitats within agricultural areas, including field margins, fallows, hedgerows, grassland, woodlots, and traditional agroforestry, represent important biodiversity refuges. However, these are under threat in light of human population growth and increasing food demand.

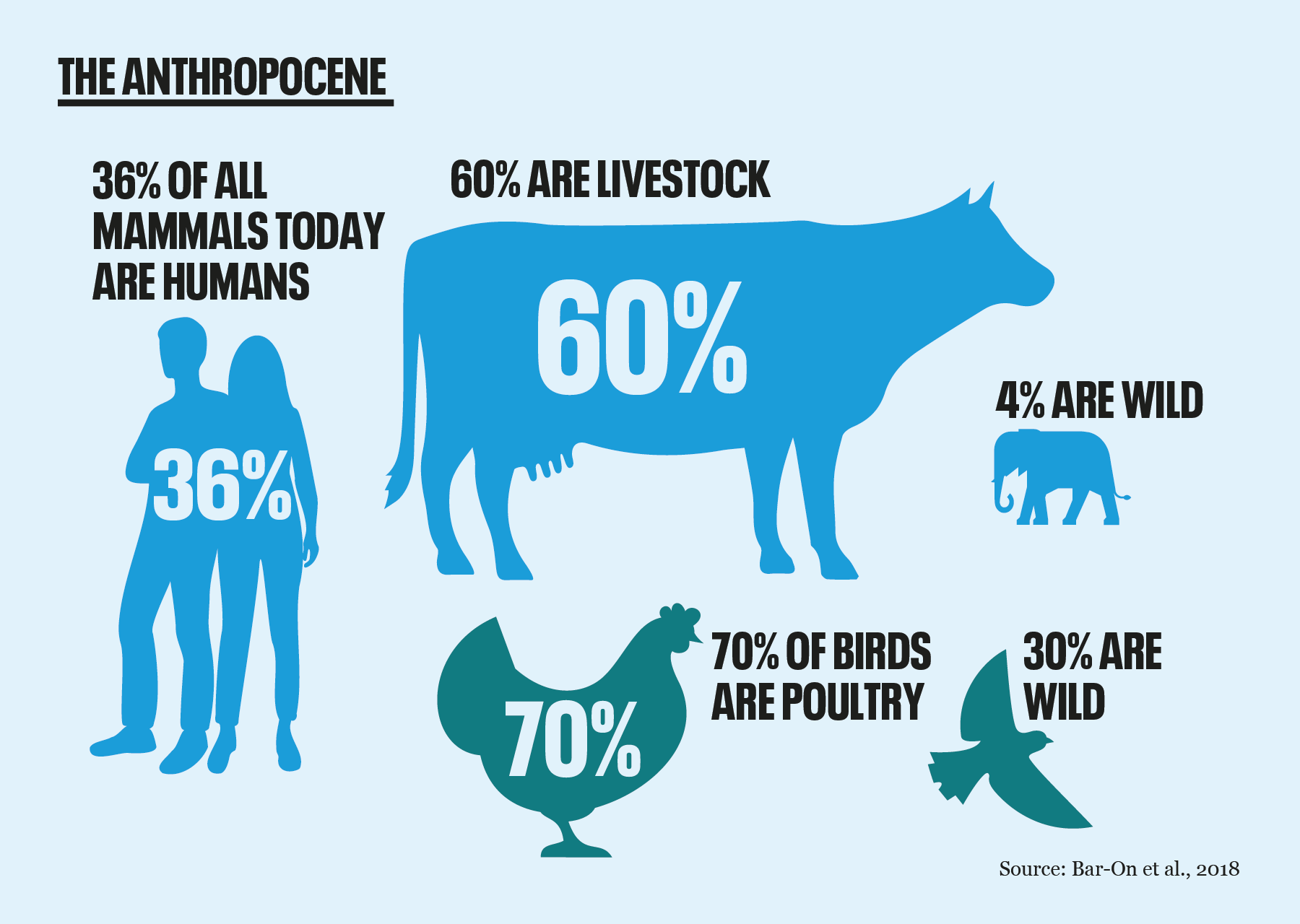

According to the UN Food and Agricultural Organisation (FAO), humanity will require 30% more food by 2030 and 50% more by 2050. Agriculture already uses 80% of the world’s extracted freshwater, occupies half of all habitable land on Earth, and is the primary driver of habitat and biodiversity loss. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species lists agriculture as a primary threat to 24,000 of the 28,000 species it has assessed so far. Eighty percent of global farmland is used to raise animals, which now account for 60% of all mammal species by mass, compared to only 4% for wild mammals. Farmed poultry represent 70% of all birds by mass, with wild birds making up only 30%. The increasing demand for meat and dairy due to a rapidly expanding middle class is particularly concerning. Farmland already covers 47% of the entire EU-28 area and growing food demand, combined with climate change, puts remaining key semi-natural areas in jeopardy.

The authors assessed four vital species groups based on their agricultural contributions to soil fertility, biological pest control and pollination; vascular plants, earthworms, spiders and wild bees. Within European farmland half of species studied were found only in semi-natural areas which constitute less than one quarter of the total land area. With one third of the food we eat depending on animal pollinators, this is an alarming finding.

The study concludes that further conversion of semi-natural habitats to agriculture should focus on areas with lower species richness like grasslands, and that organic farming practices should be prioritised as they tend to have a smaller impact on biodiversity. The authors point out that organic agriculture usually produces lower yields, however, which means they often require a larger area to meet the same demand.

The study acknowledges the need to reduce food waste and to adopt more plant-based diets, but it treats future population projections as a given rather than something we can help steer. Empowering and encouraging people to choose smaller families needs to be a part of every sustainable food strategy.