The World of Population Projections

The UN Population Projections are generally considered to be the premier forecast for future population changes, with a pretty strong history of getting it right and the most widely cited. But there are others out there, and some would argue that these alternatives are based on stronger data and more robust modelling. In this post, originally published in February 2023, Digital and Communications Manager Ben Stallworthy takes a look.

If you have a previously held interest in population, you’ll probably be aware of the UN Population Projections. Updated every two years, people widely regard them as the leading authority in the (admittedly small) field of population projections. They also receive the most frequent references. The UN released the last projections on World Population Day in July 2022.

The UN’s Past Population Growth Projections

The UN actually have a pretty good record with past projections, specifically their median scenario. In 1968 they projected 5.44b in 1990 – the actual figure was 5.38bn (0.06bn difference). In 2000, the population projected for 2020 was a little under 8bn and we hit 7.8bn (0.2bn out).

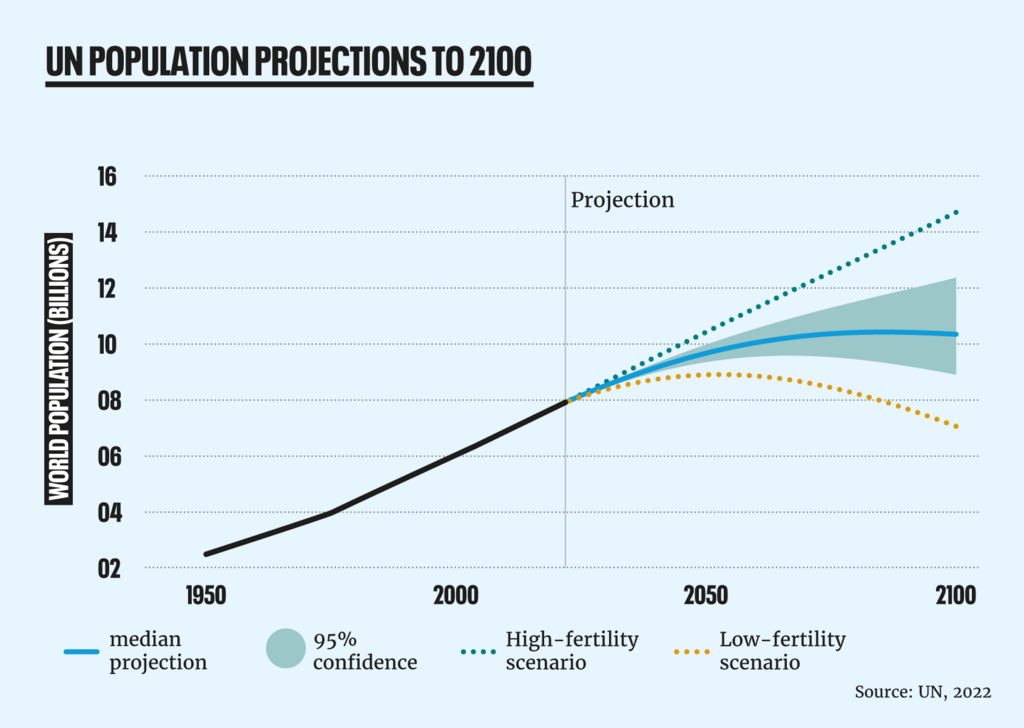

By 2019, they projected just a one-in-four chance of the global population plateauing before 2100. Responding to the evidence of growth slowing down, in 2022 it has revised its view, now envisaging a fifty-fifty chance of population growth peaking at some point between 2080 and 2100, and possibly declining by the end of the century.

So, not perfect, but they have certainly stood up to scrutiny so far. This is notable given the number of variables involved.

There are a lot of variables, however. Demographers use different approaches to forecast how these variables will affect future population growth. There is strong consensus about our trajectory. We expect continued growth into the second half of the century, followed by a peak and eventual decline. What the numbers will be, and when that peak will occur, however, is a matter of greater debate.

International Institute of Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA)

IIASA is an international research institute based near Vienna, Austria, and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change uses its modeling.

Employing a different methodology than the UN, IIASA produces a range of scenarios known as Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSP). These scenarios are based on possible developments in factors known to influence fertility rates. The primary factors considered are family planning use and education.

Their most recent scenarios and projections, Demographic and human capital scenarios for the 21st century, published in collaboration with the European Commission in 2018 are;

- SSP1, ‘Sustainability/Rapid Social Development’ in which great progress in education, use of modern family planning and economic security leads to falling family size;

- SSP2, ‘Continuation/medium population’ which is more or less our current trajectory;

- SSP3, ‘Fragmentation/Stalled Social Development’ in which things don’t go as we hope they will.

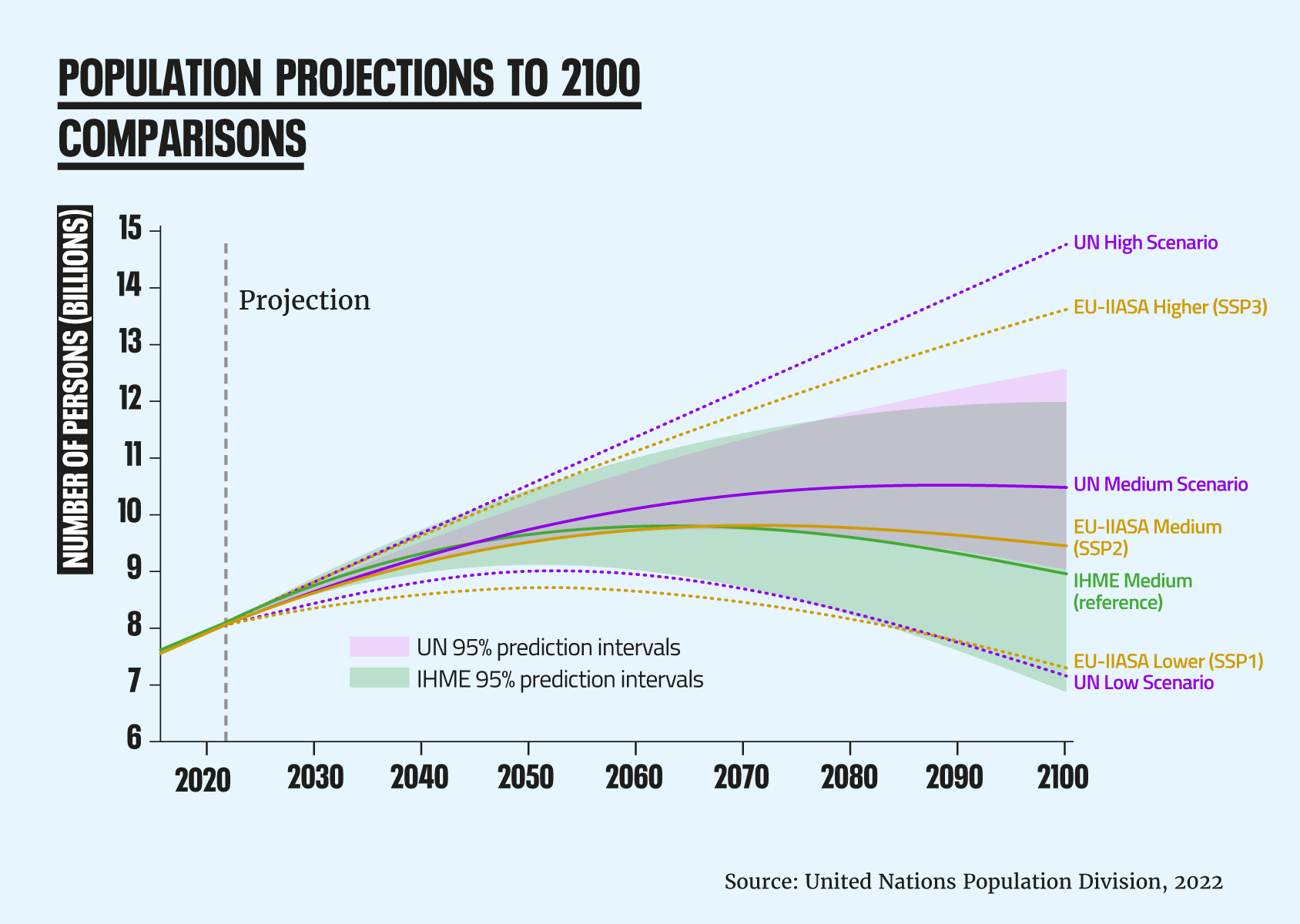

SSP1 is lower than the UN projection, with a peak of 8.7bn, declining to 7.3bn in 2100. This is an optimistic assumption, essentially reliant on us doing better than we have done so far in things like ensuring contraception access and that more children are able to complete an education.

The more likely SSP2 shows population growth peaking at 9.7bn around 2070 and still more than 8bn by the end of the century. Under SSP3, there is no peak, with population more than 13bn and still climbing in 2100.

Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington (IHME)

This research institute working in the area of global health statistics and impact evaluation at the University of Washington, Seattle, is the new kid on the block.

Published in the Lancet in 2020, IHME unpacks the factors driving fertility and produces a range of scenarios. Its main projection sees population growth peaking at 9.7bn in 2064 at a similar rate to the UN’s projections, then declining to 8.8 billion by the end of the century.

Going beyond that, the difference seems dramatic. However, long-term projections come with significant uncertainty. At the top end of the main scenario’s “95% interval,” IHME projects a global population of 11.8 billion in 2100—more than a billion higher than the UN’s current medium variant projection. Its medium projection for a “worst case” scenario is actually higher than IIASA’s – 13.6bn by the end of the century.

The IHME scenarios include lower numbers, however. In particular, it models how meeting the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) would impact fertility. The SDGs are the UN’s framework for securing human development and planetary health by 2030 – a set of 17 areas of activity, such as Zero Hunger, Gender Equality and Climate Action, each broken down into specific targets.

If we achieve the SDG targets related to education and contraception, IHME projects a global population of 6.3 billion in 2100. Sadly, this “if” is more representative of a theoretical possibility than a likely trajectory for human progress. Indeed, a number of demographers have challenged IHME’s conclusions on the basis that some of its assumptions about progress in factors driving fertility downwards are over-optimistic.

ARE THERE OTHERS?

Jorgen Randers is a quite genuine prophet of ecological collapse, having been an author of the hugely influential Limits to Growth report in 1972, which modelled future trajectories of economic activity, resource use and planetary boundaries and concluded that the then path was unsustainable.

Back then, Randers predicted a global population of 13bn by 2030 but by 2012, he had revised it substantially: “The world population will never reach nine billion people… It will peak at eight billion in 2040, and then decline.” The level and timing of that peak are at odds with almost every other projection of population growth.

Today though, even Randers no longer endorses it. In 2021, his projection estimated a peak of around 9.5 billion people in 2050, followed by a steep decline to around 6 billion by the end of the century. This would return the population to the same level it was at the start of the century, just twenty-odd years ago.

WHO’s most likely to be right?

People widely use the UN’s projections because of their longevity and, as we’ve seen, their relative accuracy. They remain the most authoritative and useful.

The main messages to take from all the projections are these:

- The population is still rising and will likely continue to do so until the second half of the century

- We are unlikely to have a lower population by 2100 than we did in 2000.

- We have the power to change how big the peak in numbers will be, and how soon it happens.

It is critical for people and the planet that we achieve the lowest of those projections. But that can’t and won’t happen unless we become more effective and successful. We must ensure that everyone can lead a safe, secure life with freedom, choices, and opportunities. Delivering the positive, empowerng solutions which will bend the population curve down needs commitment and hard work. There can be no resting on our laurels, that work must continue.