Birth control: where are the male options?

There is now a whole buffet of female contraceptive methods on the market, yet there remain only two options for men: condoms and vasectomy. Why is this?

The invention of modern contraception has profoundly changed human society for the better by giving people control over whether and when to have children. Decades of research have led to the development of pills, injections, implants, coils, patches, rings and barriers that prevent sperm from meeting egg. However, almost all of these have to be implemented by the female partner.

Unequal burden

The roll-out of the contraceptive pill in the 1960s played a key role in women’s emancipation – in England, it remains the most popular form of prescribed contraceptive. Unfortunately, hormonal contraceptives are not always without side-effects, which include serious (but thankfully rare) complications like blood clots, strokes, depression and cancer. Together with cost (in countries that don’t fully subsidise contraception) and inconvenience (such as having to remember to take it on time and obtaining prescription renewals), these burdens have been almost exclusively shouldered by women. Not to mention that globally, tubal ligation (female sterilisation) remains the most common contraception.

Increasingly, however, many men wish to play a more active role in family planning to share the burden with their partner or to take control of their own fertility. In addition, unplanned pregnancies still account for nearly half of all pregnancies worldwide. Increasing the number of options available to men could help reduce these.

Male contraception researcher Dr Stephanie Page told The Guardian:

“By not giving men options, we’re excluding half the population from helping solve that important problem. One man can father a lot of pregnancies, so it could be very impactful.”

Dude, where’s my birth control?

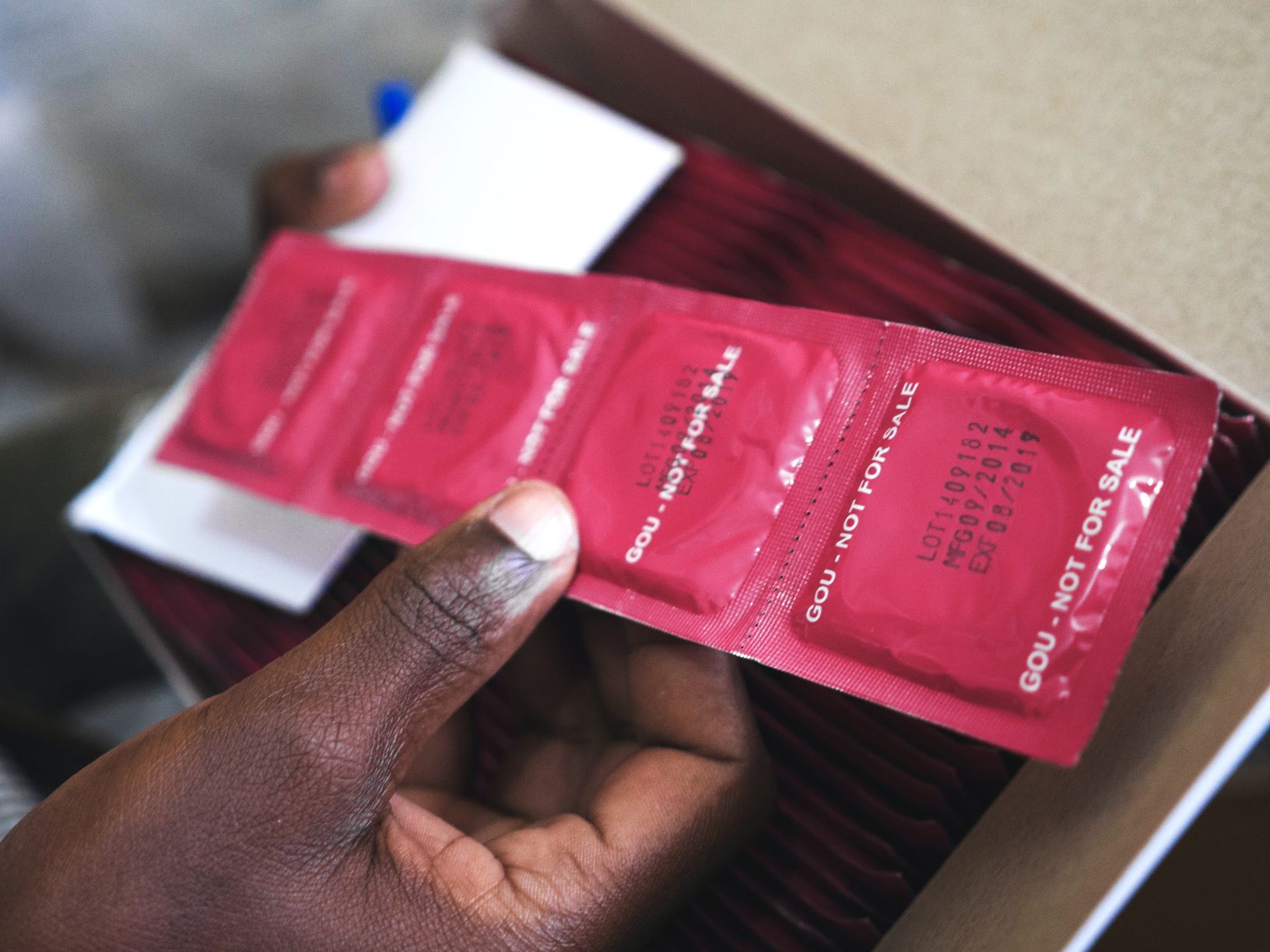

In the field of reproductive health, there is the saying that new male contraceptives have been ten years away for the past 50 years – and yes, the latter number keeps increasing. Today, men only have the choice between vasectomy (male sterilisation), and condoms – still the only reversible option for men. When used correctly, condoms are 98% effective at preventing pregnancy and they are unique among contraceptives in that they also have the amazing benefit of helping to protect against sexually transmitted infections (STIs). The reality, however, is that condoms are often used in a less-than-perfect way, meaning their effectiveness is reduced considerably. In addition, many couples prefer longer-acting methods that allow uninterrupted intimacy.

According to a survey by the US-based Male Contraceptive Initiative, almost four in ten men are very interested in potential new methods for male contraception. Among those not interested, the most stated reasons were the belief that contraception is a woman’s responsibility, fear of potential side effects, and satisfaction with current methods. As an article in Wired rightly points out:

“Some surveys show that men are reluctant, while others suggest the opposite. The most pervasive feeling might be apathy—a sense of complacency because women are running the contraceptive show.”

Men (and women) have become so used to women taking charge of pregnancy prevention that many have a hard time imagining otherwise. Old habits die hard, and we cannot expect the idea of long-acting male contraceptives to take off when none are currently available.

Traditional norms have also led to less acceptance of side effects in men. A large, promising clinical study on a hormonal injection designed to lower sperm count was halted in 2016 because of a high incidence of side-effects that women who have taken hormonal contraception are well-familiar with: acne, altered libido and mood swings. The reason many women are willing to put up with these is because they are still preferable to an unwanted pregnancy – a potentially life-threatening, life-changing condition. As men can’t get pregnant, the trade-off is not the same. Importantly though, three-quarters of the study participants said they would be willing to continue with the contraceptive jab. The decision to end the trials was made not because of a high dropout rate, but because the project’s review panel concluded that the risks outweighed the benefits.

The biggest hindrance to the development of new male contraceptives is lack of investment, which itself is heavily influenced by social and cultural barriers. Clinical trials are expensive and pharmaceutical companies are reluctant to fund them because of perceived unprofitability. Even the World Health Organisation (WHO) supported promising research involving 1,500 participants in the 1990s, but the work ended when the funding ran out. As the push among consumers for more male options hasn’t been overwhelmingly strong, the drug industry still doesn’t view it as a worthwhile investment.

Current developments

Despite the lack of funding, several exciting research projects on reversible, long-acting methods are underway, involving both hormonal and non-hormonal methods. One of the methods that’s furthest along is a gel containing testosterone and a synthetic analogue of progesterone, developed by the Population Council. Applied to the shoulders once a day, the gel has so far proven to be well-tolerated and effective. Many studies have looked into oral pills – a 2019 trial showed promising results for a compound called dimethandrolone undecanoate (DMAU), but more research is needed to determine long-term efficacy and safety.

Among non-hormonal methods, a lab in India is currently one of the frontrunners with their ‘RISUG’ method, which is short for ‘Reversible Inhibition of Sperm Under Guidance’. This involves injecting a polymer into the vas deferens – the tube that carries sperm to the ejaculatory duct – causing a physical blockage. A version of this called ‘Vasalgel’ is being developed in the US. This “nonsurgical vasectomy” has gained a lot of media attention but its safety and claim of reversibility have yet to be further investigated.

Beginning in the 1970s, frustrated with the slow rate of medical progress, a group of dedicated Frenchmen decided to take matters into their own hands. Inspired by the feminist movement and the desire to share the burden with their female partners, Pierre Colin and friends developed a type of “contraceptive underwear” – essentially a modified jockstrap which reduces sperm production by elevating the temperature of the testicles. (If you’re feeling creative, why not give this modified bra version a try?). The downside is the contraption has to be worn for at least 15 hours a day for three months before the sperm count is low enough to prevent pregnancy. Perhaps a bit of a hard sell?

Unfortunately, unless the funding shortage is tackled, experts say it’ll take another 15-20 years for new drugs and 5-10 years for new devices to become publicly available, meaning many of the researchers and participants involved in current trials won’t personally benefit from their contributions. Nevertheless, we salute them for laying the much-needed groundwork for a more equal society in which everyone is empowered to plan their family.