Conservation through education and family planning: Reporting from Colombia

Between July 2021 and February 2022, Empower to Plan supported Women for Conservation in the provision of environmental education workshops and family planning clinics in biodiversity hotspots of Colombia. Our Empower to Plan Project Coordinator, Catriona Spaven-Donn, visited Women for Conservation over International Women’s Day in March. In this field report, she reflects on how the group is empowering women to protect endangered species and their habitats as well as become decision and change-makers in their own lives.

It is 6am and already the heat is intensifying as we descend from the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta to one of the low-lying regions near the coast. Today, we are traveling to the Zona Bananera region with Women for Conservation and their partner and national sexual and reproductive health provider, Profamilia. In the small community of Guacamayal, 25 young women are eagerly waiting to be seen by Profamilia medical staff as part of the three-month check-up after receiving their contraceptive implants.

The Zona Bananera is a municipality of Santa Marta in northern Colombia. The region includes two protected areas that are home to numerous native species, such as the Colombian red howler monkey and slider turtle. However, this land around the Magdalena River, which is an internationally recognised wetland site, is now predominantly occupied by banana monocrops. The crops divert water from the Sierra Nevada’s river system into crop irrigation, degrading the ecosystem and leaving the local population without drinking water.

Meanwhile, local farmers producing diversified crops of yucca, yam and chilli, are forced off their land as dry seasons intensify and yields reduce. When they sell their land in desperation, often it ends up in the hands of large-scale banana farmers and multinational corporations. In many cases, the former land-holders then end up working on that same land as wage-labourers.

Kelly Donado, Women for Conservation’s Programme Coordinator, comments that one would think of the banana-growing region as a place that’s rich in resources, income and infrastructure. But, she says, “everything is exported. All the food that is grown here, they take it away. And meanwhile, there is a total lack of basic services. Women have to walk very far to get to health centres and once they get there, the services are inadequate.”

Kelly grew up feeling this need in her local community first hand. In her mountain village in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, she is “community mother” who liaises between local authorities and neighbours, including getting food into the community when roads were blocked and markets shut down during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Kelly makes things happen. So, when she saw the impact of Women for Conservation’s family planning, sustainable livelihood and nature education programmes in the Sierra, she decided the same successes should be replicated in other parts of the Magdalena department.

“We are a cancer for the earth – the rivers are becoming polluted and nature is ever more impacted [by people]. We need to become water protectors. When there’s ever less food, jobs and water, it scares me to think of bringing more babies into the world. What kind of situation are we bringing them into? When girls have unplanned pregnancies, they cannot be adequate carers and often, they’re not able to provide for their babies.”

– Kelly Donado, Women for Conservation Project Coordinator

After reaching 115 women in Santa Marta with Women for Conservation’s integrated programmes, the group have now extended their services to 137 women in some of the most marginalised communities of the Zona Bananera. The demand for family planning services is so high that there are already 190 more women waiting to be included in Women for Conservation’s programming.

Given the lack of a nearby health centre, Kelly’s sister Danisa, a local nurse, offers her house and garden for the family planning clinic. She speaks openly about the challenges in the community, where sexual abuse cases abound and it is common to see 12 and 13-year-olds with babies. Kelly and Danisa lament, “these are 13-year-olds that have only just stopped playing with dolls and now they’ve got a baby in their arms.”

In November, Profamilia and Women for Conservation arrived in Guacamayal to give a sex education session. They later returned to provide implants to the first group of 137 girls and women, and now they have come back for a private consultation with each patient. Many of the women present are anxious that their periods haven’t arrived or they have questions about the effectiveness of the implant. They are evidently relieved to receive factual, science-based and reassuring information from the medical staff.

Profamilia is a private sexual and reproductive health service that is efficient and professional. Women for Conservation covers the costs of women traveling from their remote communities to Santa Marta, as well as the treatment at Profamilia’s clinic. For tubal ligation treatments, Women for Conservation also covers the cost of 2-3 nights in a hotel so that the women can recuperate before returning to their communities.

Andris, a 19-year-old mother of two, wishes she had known about and had access to contraceptive methods earlier: “When I got pregnant, I was too embarrassed to stay in school. If I had heard about the family planning clinic earlier, I could have avoided pregnancy. I’m not going to have another one now, that would only set me back more. In the future, I’d like to study and I also want my children to study. If the mother succeeds, her children can as well. They can do what I didn’t manage to do.”

She remembers that when she was still at school, she had a notebook full of drawings. She wanted to be a fashion designer. She still thinks of this dream sometimes, but is not optimistic that she will be able to achieve it. “In this town, there aren’t any opportunities. Nothing happens here. If I want to succeed, I’d have to move away, but how can I do that when I have two children to support?”

Linda, a 20-year-old mother of a 2-year-old boy, is equally articulate about the challenges of living in the Zona Bananera. However, she says, “I won’t let the doors close on me. I deserve to have a good job and a dignified life, so that I can provide for my child.” She is studying administration in the city of Santa Marta on Sundays and works for a company from Monday-Friday. “We need to have better education in all senses, but especially on the theme of sexual health and relationships. We bring children into this world and then don’t know what to do with them – we don’t have food, we can’t feed them. To plan a child is to have dignity and be healthy.”

She concludes that Women for Conservation has made a unique and important impact in her community, as with the contraceptive implant, young women can stay in school and avoid getting pregnant. “Personally, I decided to get the implant because it’s necessary to prevent unwanted and early pregnancies. This programme has helped us a lot because here in the community where we live, there are many, many girls who haven’t finished school, and they’re already pregnant.”

Profamilia is delighted that they have managed to provide family planning clinics in hard-to-reach and marginalised areas of Santa Marta, in communities where they wouldn’t have been able to go if not for Women for Conservation’s collaboration. It is difficult to arrive in areas with very little public health coverage or sex education provision. When Women for Conservation first started with their family planning programmes and relied upon Colombia’s public health service, EPS, the bureaucracy around applying for and being provided with a contraceptive method often took weeks or even months. Kelly saw three girls get pregnant in the time it took after soliciting the implant and waiting weeks for it to become available. As Linda says, comprehensive and integral sex education is sorely needed in these communities.

“Sexual and reproductive rights are part of caring for ourselves… if we take care of ourselves, we are also giving back to our local environment. If I plan my family, I am thinking about nature, food, the land and the conservation of our ecosystems. It all links in with sexual health.”

– Catizza Montenegro Diaz, Psychologist and Profamilia Community Outreach Director

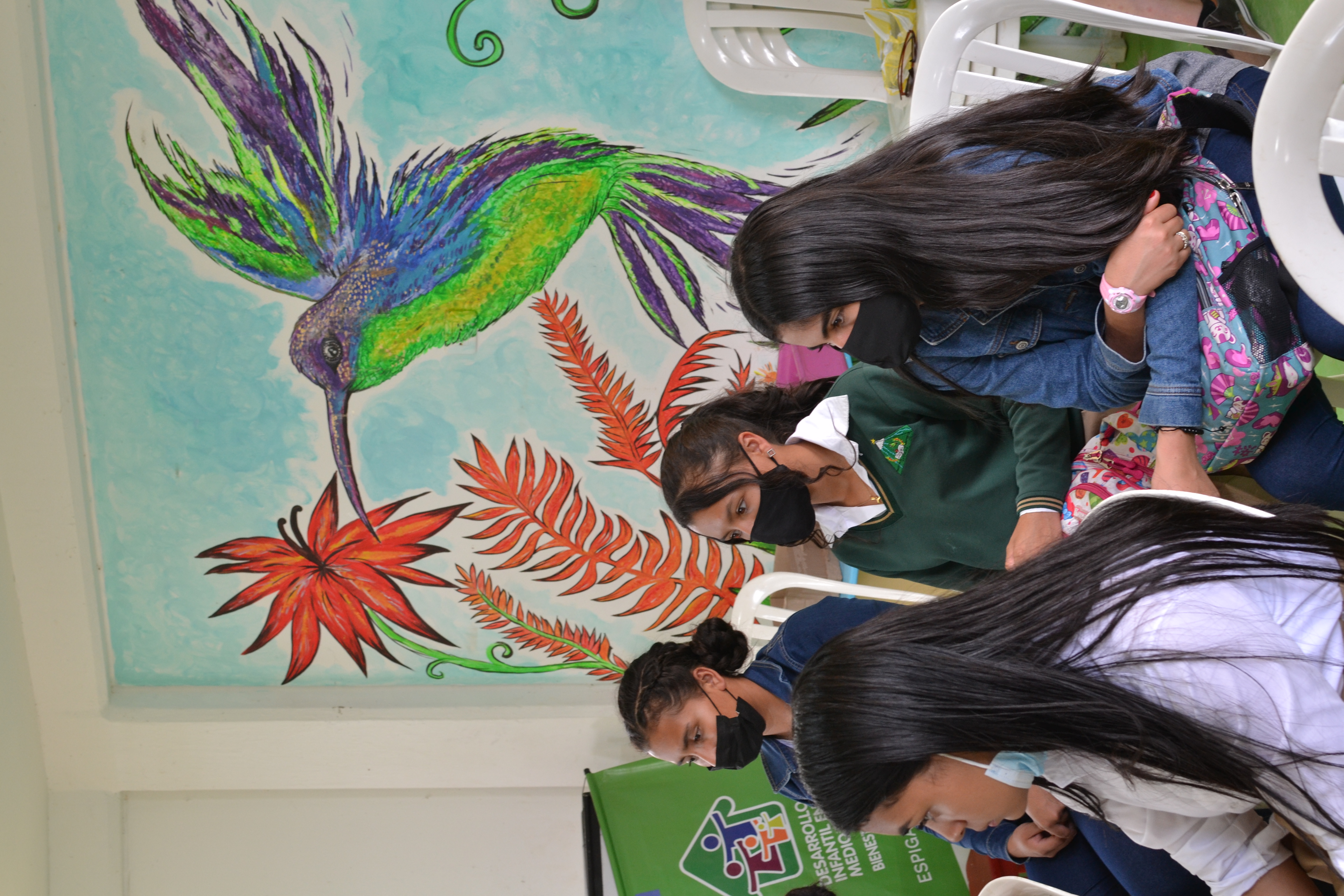

Over 1,000 metres up from Santa Marta on the Caribbean coast, the small community of Vista Nieve (“snow view”) is home to one of the only schools in the area. Boarders aged between 8-18 stay at the school during the week and travel hours back to their remote communities at the weekend. Kelly leads art and environmental education classes at the school, which is also where her own children study.

During our Empower to Plan visit to Vista Nieve, Juan Carlos, an ornithologist working at the nearby El Dorado ProAves Nature Reserve, gives a birdwatching class. He encourages the group of teenagers to consider why, where and how to observe birds. This is an especially important activity in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, home to around 20 endemic bird species only found in these isolated mountains, the highest coastal range in the world. Colombia is the world’s number one place for bird biodiversity and over 600 species can be found in Santa Marta.

Giseth is 15-years-old and is in her second last year of school. After two years of virtual classes with an unreliable internet connection, she is delighted to be back to in-person classes and is already thinking about studying Communication and Psychology at university. “I love watching programmes about animals,” she says, “but until now, I hadn’t paid much attention to birds. Now I know what some of them are called and I’ve learned how to look for them with binoculars… Living here, we have a strong connection with nature.”

This connection is also evident during the International Women’s Day celebration in Minca, one of the Sierra Nevada’s main towns. On 8th March, the small main square fills up with women activists and artisans to share music, art and an appreciation for women’s role in conservation and nature protection. Around 15 participants of Women for Conservation’s sustainable livelihoods programme have travelled from the higher altitude regions of Santa Marta to celebrate and join other local women artisans in selling jewellery and beadwork.

During the event, we hear about the importance of women’s right to education, to the vote, to holding legal titles to land. Meanwhile, an arts and crafts table encourages children to use recycled materials to create collages inspired by nature conservation and bee protection. A group of local children sing a song of appreciation to the water, including words in Kogui, one of the region’s three indigenous languages – the others are Arahuaco and Wiwa.

The Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta is undeniably one of the most important regions in the world for biodiversity. The Wiwa indigenous community feels closely interconnected with the region’s native bird species; they identify with them through specific personal characteristics. For example, for them, the crimson-crested woodpecker represents Wiwa women.

In the El Dorado Nature Reserve, we hike to a viewpoint where we see both the distant snow-covered peaks in Kogui indigenous territory and the nearby expanse of the Caribbean Sea. We see the dawn rising over the layers of mountains and as we watch out for the endangered endemic Santa Marta parakeet, we’re lucky enough to catch a glimpse of a white-tipped quetzal and an endemic Sierra Nevada brushfinch.

As deforestation and habitat loss drive up extinction rates in this incredible ecosystem, conservation, environmental education and family planning have never been more important. By addressing all three needs at once, Women for Conservation is creating a ripple effect of change as local girls and women become nature and water protectors with the ability to make decisions about their bodies, their families and their futures.

Thank you to all of our Empower to Plan supporters who have contributed to making Women for Conservation’s programmes possible.