UN: 2.4bn more people but is end of growth in sight?

Three years after it last did so, the United Nations has today released its updated projections for global, regional and national population change up to 2100. Its key conclusion is that there will likely be another 2.4 billion people on the planet by the 2080s, but for the first time it predicts that the world population will peak during this century and then slowly start to decline. PM’s Monica Scigliano reports on the key data, trends, and what it all means.

POPULATION PROJECTIONS

World Population Prospects 2022 is the most recent set of projections from the United Nations Population Division (UNPD). These are normally released every two years but on this occasion were delayed by the coronavirus pandemic. While other organisations also make detailed projections, the UN’s have traditionally been seen as the most authoritative, and have a good track record of accuracy on the global scale.

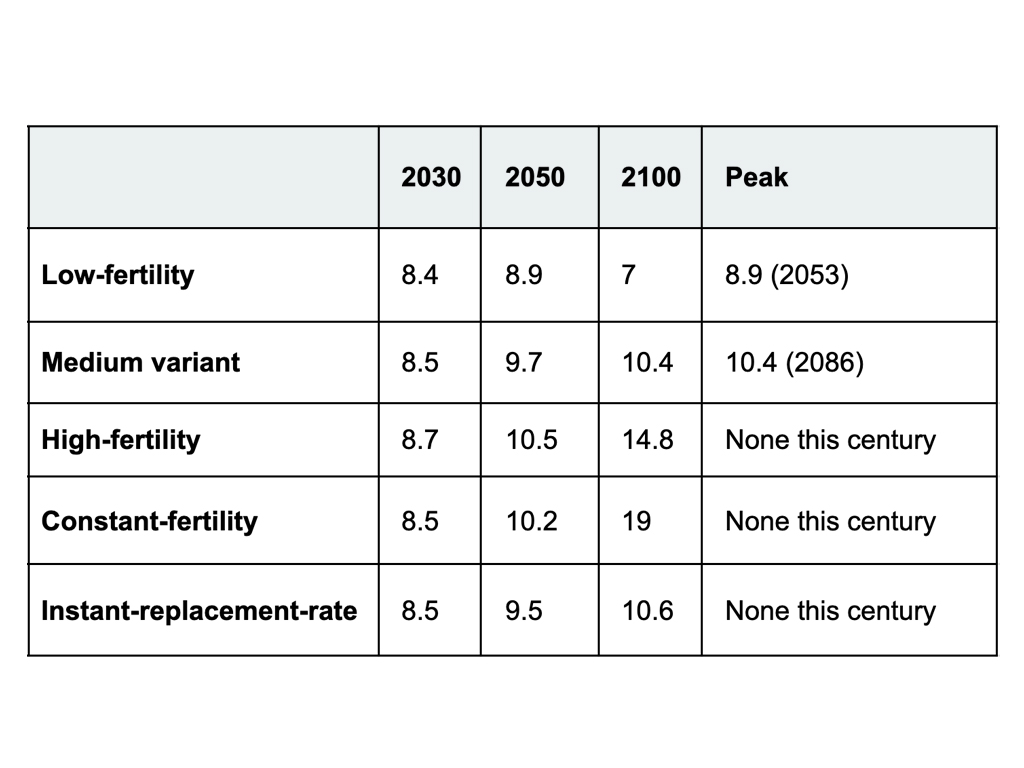

Its most likely projection (called the medium variant) is for a population of 8.5 billion (bn) in 2030, 9.7bn in 2050 and 10.4bn in 2100.

Current world population

The UN uses past trends in fertility, mortality, and migration for each country to project future population sizes, under the assumption that these trends will continue into the future. So, for example, the UN assumes that fertility rates will continue to decrease in places where they are still high and to increase very slightly in low-fertility countries. Just as with all expert projections on future population, with each generation these projections accumulate more assumptions, so there is much less certainty about the size of the population in 2100 than in 2050.

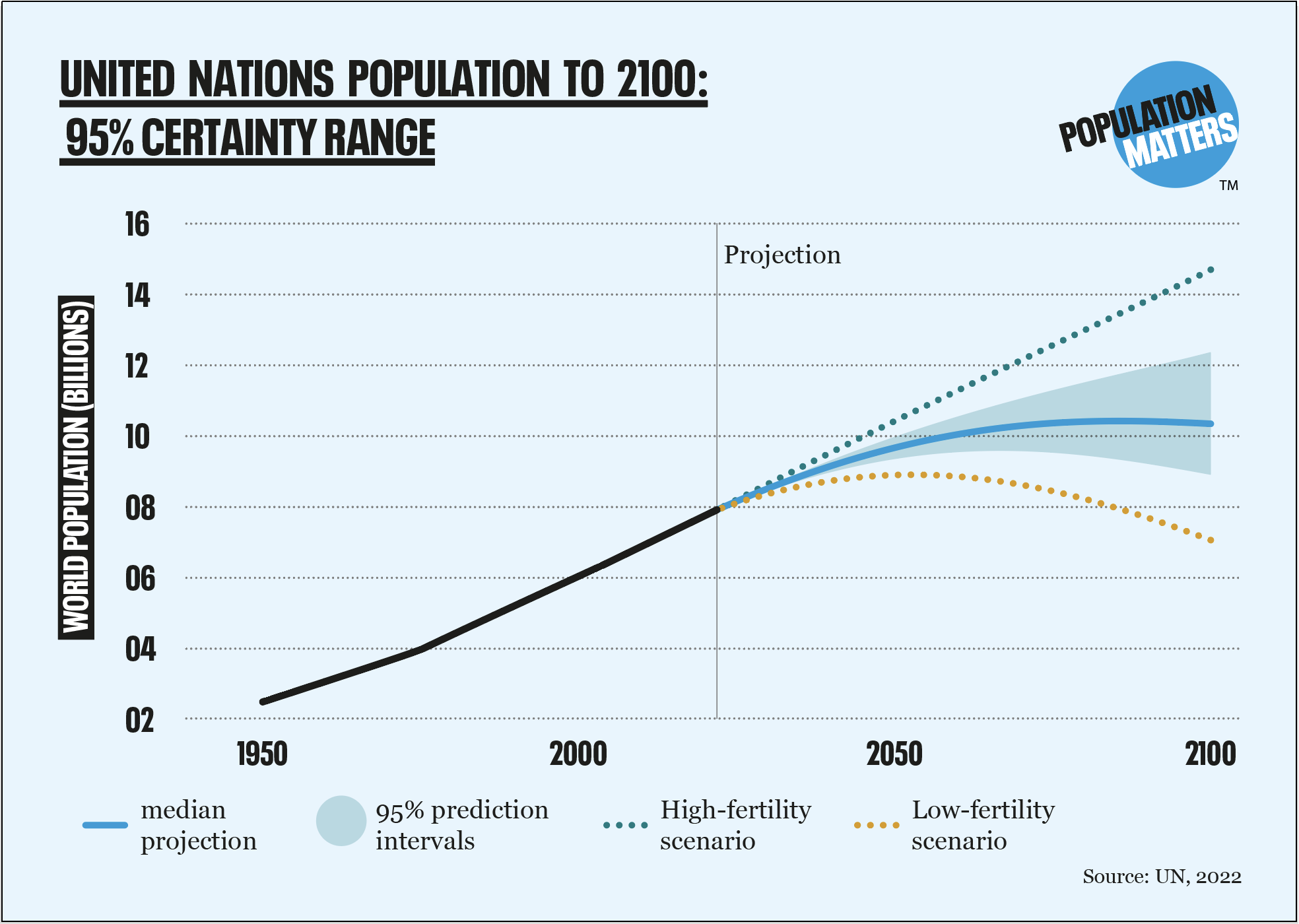

That is why the UN also provides the 95% “prediction interval” – the range that they calculate there is a 95% probability that the population will fall within. For 2050, this is between 9.4 and 10.0 billion, and for 2100, a far wider range of between 8.9 and 12.4 billion.

A complicated picture

Many factors affect the number of babies being born each year. Still, globally, almost half of all pregnancies are unintended and hundreds of millions of women have an unmet need for modern contraception. Education, poverty levels and the desired number of children people wish to have are among other important factors. To reflect the uncertainty surrounding how these may change in future, the UN also produces scenarios, which explore how different assumptions about fertility (average number of children per woman), mortality (deaths as a proportion of the population), and migration trends in each country would affect the overall population figures.

The low-fertility scenario assumes that every other woman will have one fewer child than predicted in the medium variant. The high-fertility scenario, on the other hand, assumes that every other woman will have one more child. The constant-fertility scenario projects what would happen if fertility rates were to remain exactly the same as they are now in each country. And the instant-replacement-fertility scenario assumes that in each country, fertility immediately either decreases or increases to the rate it would take to replace each generation. In each of these scenarios, as well as the medium variant, the latest projections match the previous projections released in 2019, except for the 2100 projections, which are now a bit lower. The figures are (in billions):

Why is the population still growing?

Despite frequent media stories about an impending “baby bust”, the UN’s latest projections make clear that there is no cause for alarm: the world population is likely to continue growing for several decades, with a 50% chance of peaking before the end of the century – meaning, of course, there is also a 50% chance it will still be growing by the end of the century.

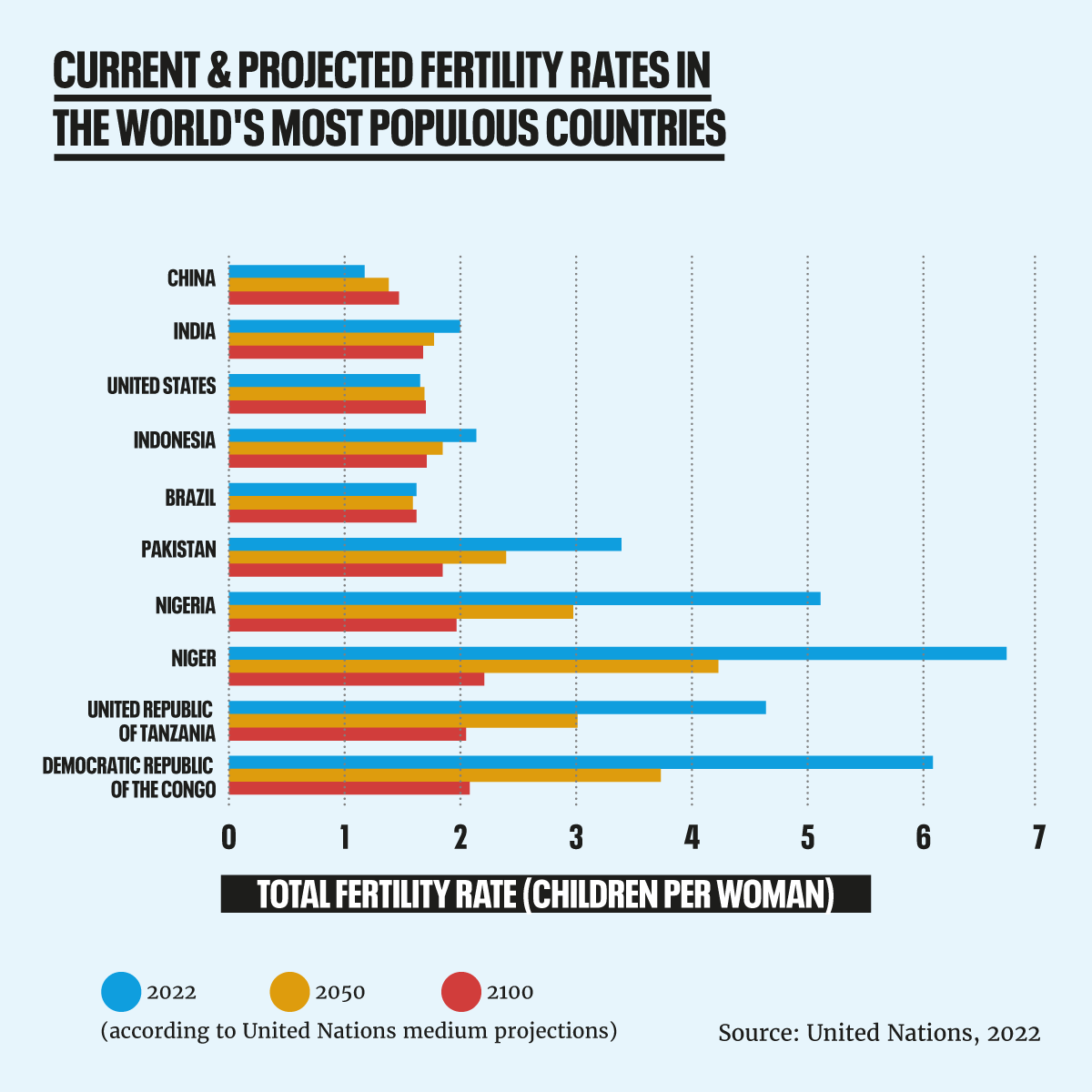

The global average fertility rate is now about 2.3, and is expected to decrease to 2.1 in 2050, reflecting advancements in education, healthcare, and gender equality, as well as optimism about future improvements. Even though the growth rate is now about 0.8% each year, with a large population that still means a lot of growth: if fertility rates remain exactly the same as they are now, the population would reach 19 billion by the end of the century. Moreover, continued population growth reflects a phenomenon called population momentum: though fertility rates are lower now than they were a generation ago, high fertility in the past means that there are now more people of reproductive age than before. This means that some growth is inevitable. However, one-third of growth through 2050 will not be explained by this momentum. And in sub-Saharan Africa, due to sustained high fertility rates, two-thirds of growth will be explained by fertility and mortality rates, rather than momentum. Regardless, fertility rate declines now will have a greater impact in the second half of the century than they will through 2050.

Decreasing mortality rates also contribute to population growth: life expectancy increased by 9 years from 1990 to 2019, meaning more people are alive at any given time. Though it then fell from 72.8 years in 2019 to 71 years in 2021 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, life expectancy is expected to rebound within the next couple of years and to reach 77 years in 2050.

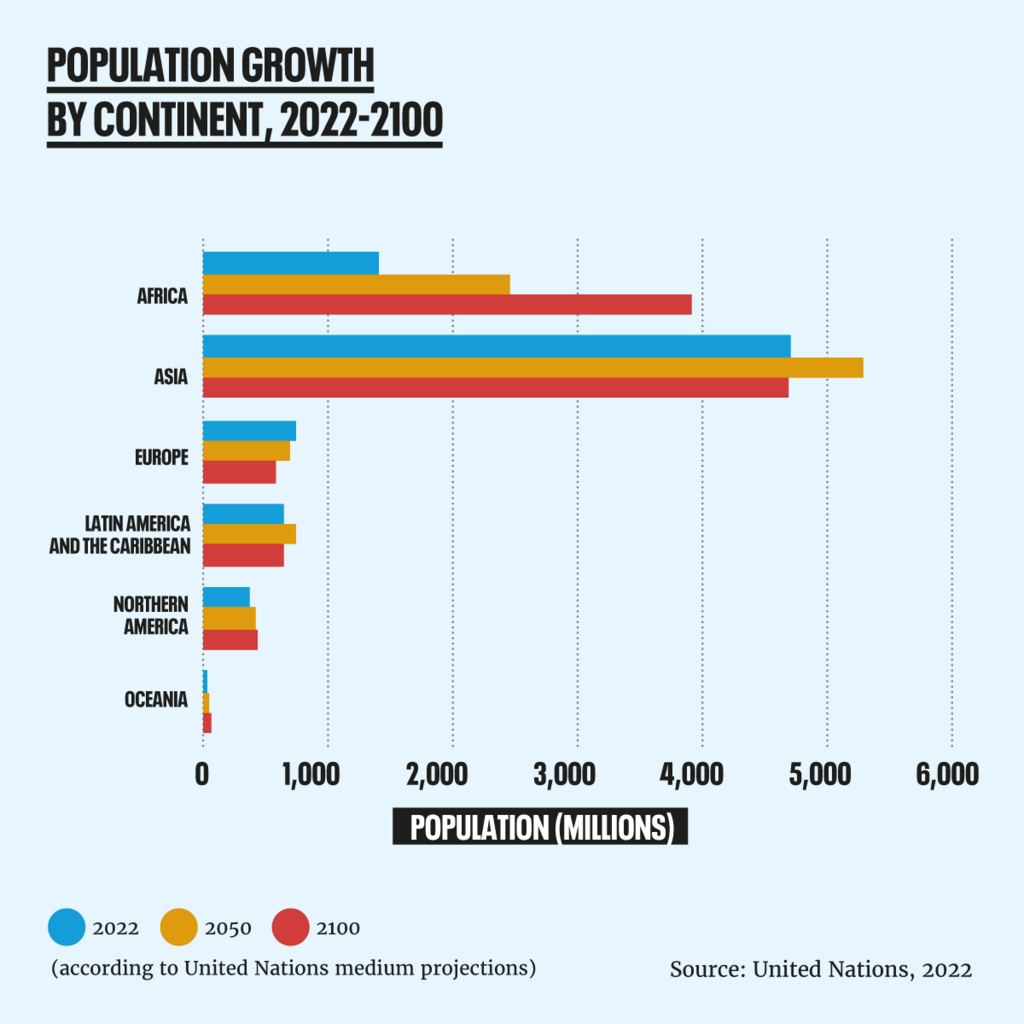

THE HOTSPOTS OF POPULATION GROWTH

Due to its higher fertility rates, sub-Saharan Africa will experience more than half of projected global population growth through 2050, doubling in size by then and becoming the most populous region in the late 2060s. Eastern and South-Eastern Asia and Central and Southern Asia – currently the two largest regions – will continue to grow, but will peak in the next few decades. More than half of global growth until 2050 will occur in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Egypt, Ethiopia, India, Nigeria, Pakistan, Philippines, and Tanzania. India is expected to replace China as the most populous country next year, when China’s population is expected to start declining.

Population decline in some parts of the world is no cause for panic

The populations of several regions are expected to start declining before 2100, with 61 countries expected to experience a decline of at least 1% through 2050. In some countries, like Bulgaria, Latvia, Lithuania, Serbia, and Ukraine, that decline is expected to be pretty severe, exacerbated in many cases by high emigration. But in most places, population decline will likely be gradual. The population of North America and Europe as a whole is expected to decrease from 1.13 billion in 2038 to 1 billion in 2100 – hardly a collapse. The UN summary report noted that the region of Europe and North America still has one of the highest percentages of people aged 25-64, which is favourable for economic performance.

Globally, people aged 65 and older outnumbered children under five for the first time in 2018, but this means there are still many more young dependants (people considered too young or old to support themselves) than old. Still, the world will continue to age, with the percentage of people 65 or older expected to rise from 10% today to 16% in 2050. While greater uncertainty exists for 2100 projections, people 65 and older are expected to make up a quarter of the world population by the end of the century, though even then, the percentage of people over 70 will still be lower than the percentage under 20 (18% and 22%, respectively).

Population Matters’ 2021 report, Silver Linings, Not Silver Burdens examined in depth how concerns about ageing populations tend to both exaggerate the extent of the problem, and underestimate the availability of practical solutions.

We’re not there yet

World Population Prospects 2022 reveals that there is still a lot of progress to be made. For example, 10% of babies are still born to adolescent girls, for whom pregnancy is the leading killer. Additionally, the UN warns that rapid population growth makes sustainable development more difficult – an issue explored in Population Matters’ 2020 report, Hitting the targets. In the UN’s words, high population growth can:

“potentially trap communities in a vicious cycle: while economic growth may struggle to keep pace with population growth, poverty can deprive individuals of opportunities and choices, limiting their ability to control their fertility, perpetuating high levels of childbearing often starting early in life and ensuring the continued rapid growth of the population.”

Indeed, the 46 fastest growing countries are also some of the most impoverished and most vulnerable to climate change. The UN also acknowledges the role of population growth as a multiplier of environmental impact. Ensuring that all people have the full freedom to choose how many children they have is important for its own sake, but will also contribute to economic development where it is needed and ease pressure on the environment.