Gender-based Violence, unplanned pregnancies and the condom conundrum

Despite being acknowledged as a global public health issue by the World Health Organization, Violence Against Women and Girls, or gender-based violence, continues around the world. Our Content and Campaigns Specialist, Florence Blondel, delves into the intricate links between GBV, unintended pregnancies, rising fertility rates, sexually transmitted diseases, and the disempowerment of the abused.

Globally, Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 5, focusing on gender equality, lacks prioritisation, leaving around 245 million women and girls (aged 15+) enduring physical and/or sexual violence from an intimate partner annually. The 2023 Gender Snapshot report attributes the failure to eradicate intimate partner violence (IPV) or spousal violence, an SDG 5 indicator, to ‘lacklustre commitment’ to gender equality on a global scale.

Deeply rooted biases against women, manifesting in unequal access to sexual and reproductive health, unequal political representation, economic disparities and a lack of legal protection, among other issues, prevent tangible progress.”

The 2023 Gender Snapshot report

In certain regions, women and girls resort to intentional pregnancies as a means to escape violence, while others face unplanned pregnancies due to restricted contraceptive use. Additionally, some women and girls are compelled to live with sexually transmitted infections (STIs) like HIV and in this group, we include the nonconsenting 650 million girls and women alive today who were married before their 18th birthday. In most countries, sexual violence is more common than physical and emotional violence among younger women than older women. This blog primarily examines instances of IPV looking at sexual violence in particular, featuring case studies from Bolivia, Nepal, and Uganda.

Pregnancy as a way out – or not

In a deeply patriarchal society like Nepal, there’s a prevailing assumption that becoming pregnant and giving birth might decrease the risk of sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV).

In Nepal, fertility is highly valued, and a woman’s ability to become pregnant and to give birth is often closely linked to her worth. Therefore, becoming pregnant and giving birth may protect newly married women from violence perpetrated in the home by partners and family members, due to a desire from the family to ensure that the fetus is healthy.”

Is there an association between fertility and domestic violence in Nepal?, a report in Science Direct

However, researchers found this is not the case for many women. Pregnancy, at times arising from violent circumstances, has been identified as a cause of stress for men. Additionally, some women may face accusations of deliberately becoming pregnant to evade household responsibilities. Culturally specific forms of violence experienced by pregnant women in Nepal include pressure to bear sons, denial of food, and forced strenuous physical work during pregnancy.

…after a woman accomplishes the important “responsibility” of reproducing, her status diminishes and the risk of violence increases.”

Is there an association between fertility and domestic violence in Nepal?, a report in Science Direct

This back and forth affects women’s reproductive autonomy and could result in women wanting to have fewer or no children as a protection mechanism. In this complex situation, there seems to be no clear resolution.

According to the latest Nepal Demographic and Health Survey, around 26% of ever-married women (15-49) have experienced spousal physical, sexual, or emotional violence, with 7% reporting sexual violence, often involving physical force by their husbands. Unfortunately, as many as 7 in ten women do not seek help. Unfortunately, many affected women do not seek help, leading to enduring challenges such as unplanned pregnancies and STIs, which could be prevented through early reporting.

Increased marital fertility rates

In a study focused on the Tsimane people in Bolivia, researchers from French and U.S. institutions discovered a correlation between IPV and higher marital fertility rates. Approximately 85% of women across five villages reported being victims of spousal abuse. In their study, women who experienced abuse tended to have more children than those who were not abused. Notably, the abused women were more likely to give birth in the year following the occurrence of the abuse.

These findings are detailed in their paper published in the journal Nature Human Behavior. This is similar to Uganda where “women who experienced violence were significantly more likely to have more children than non-abused women”. And just like in Nepal, IPV strips women of their reproductive autonomy.

IPV, HIV risk and child sexual abuse

In Uganda, six in every 10 women have experienced sexual violence before the age of 15. Every day about 40 young girls are defiled (aggravated sexual abuse of minors). These reported cases are just the tip of the iceberg in a country that ranks among the top 20 where children are married before reaching 18 (34%), often residing with older men, some in polygamous unions. In Uganda’s 2022 Violence Against Women Report, of the 14,134 defilement cases reported in 2020, about 1,300 were children aged 0-8 and 3,000 aged 9-14 years. Disturbingly, over 300 victims of defilement were abused by HIV-positive individuals.

In 2020, around 30,000 cases of STIs due to gender-based violence were documented (29.7% males; 70.3% females), marking a 5.6% increase from 2019. Negotiating condom use is hard for many.

Less than one in ten women who experienced violence asked their partners to use a condom (6%), only 63% of their partners indeed refused to use a condom. Therefore, condom use is low among violated women and hence a higher risk of exposure to STIs/HIV.”

According to UNAIDS, in countries with high HIV prevalence like Uganda, ‘intimate partner violence can increase the chances of women acquiring HIV by up to 50%’.

This pandemic of violence continues to drive thousands of new HIV infections every week and is making the end of AIDS much harder to achieve. It is a systemic issue that must be addressed at every level of society.”

Winnie Byanyima, ED, UNAIDS

It’s the culture

Shockingly, for women whose partners paid bride price and dowry, approximately six in every 10 experienced either physical or sexual violence, or a combination of both, from their partners.

Culture is a major driver of intimate partner violence as it dictates certain practices that promote the vice.”

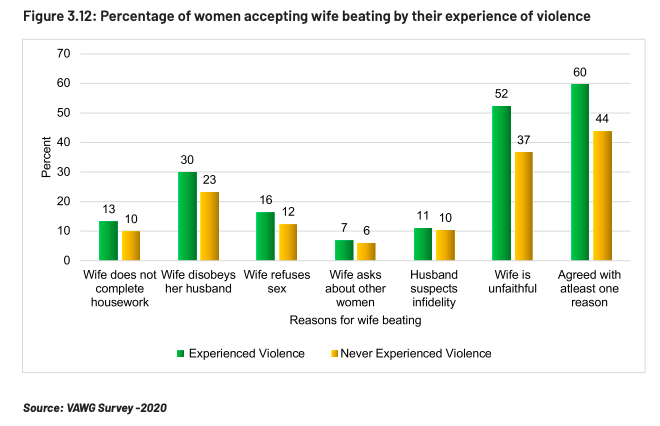

Sadly, violence against women is accepted even by victims.

How do we get there?

Although achieving gender equality, and subsequently putting an end to the widespread abuse faced by girls and women, might take up to 300 years due to chronic underinvestment and persistent patriarchal ideologies. But there are ongoing efforts aimed at moving us closer to this goal. The UK government, led by the Special Envoy for Gender Equality, is resolute in promoting the progress of women and girls globally through a strategic approach focused on the three Es: Education, Empowerment, and Ending Violence, as outlined in its White Paper and first International Women and Girls Strategy, 2023–2030.

Girls who have higher education are up to six times less likely to marry as children and less likely to experience violence from a partner.”

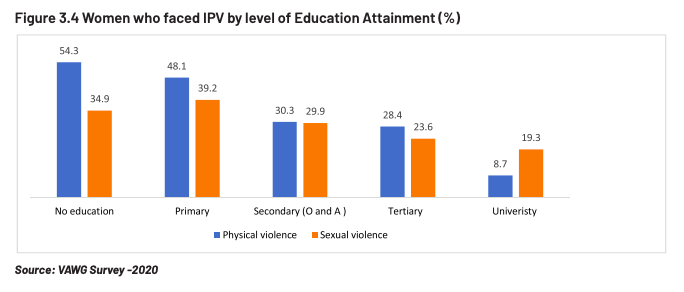

It is crucial to emphasize the importance of investing in the education of girls. In Uganda, evidence shows that women and girls with higher education experience lower rates of IPV.

Similarly, in Nepal, the positive impact of education becomes evident as women’s ability to negotiate safer sexual relations tends to increase with higher education levels. Educated women are empowered to assert their rights, such as requesting condom use or refusing sex for any reason. This stands in stark contrast to the higher vulnerability (9%) to sexual violence observed among women with only primary or no education compared to their more educated counterparts (4%).

Tackling gender-based violence

Beyond advancing educational initiatives, more nations must establish and enforce domestic violence legislation. The United Nations underscores that countries with such laws tend to exhibit lower rates of intimate partner violence. Even in nations like the UK, committed to eradicating VAWG, the persistence of this widespread issue is evident, with ‘4.4% of individuals aged 16 years and over (2.1 million) having experienced domestic abuse in the last year.’

The stark reality remains that, unless we intensify our efforts, attaining gender equality might require an estimated 300 years. The urgency to address and combat gender-based violence is paramount for the collective pursuit of a more equitable and just society.