Cracking knuckles and counting kids

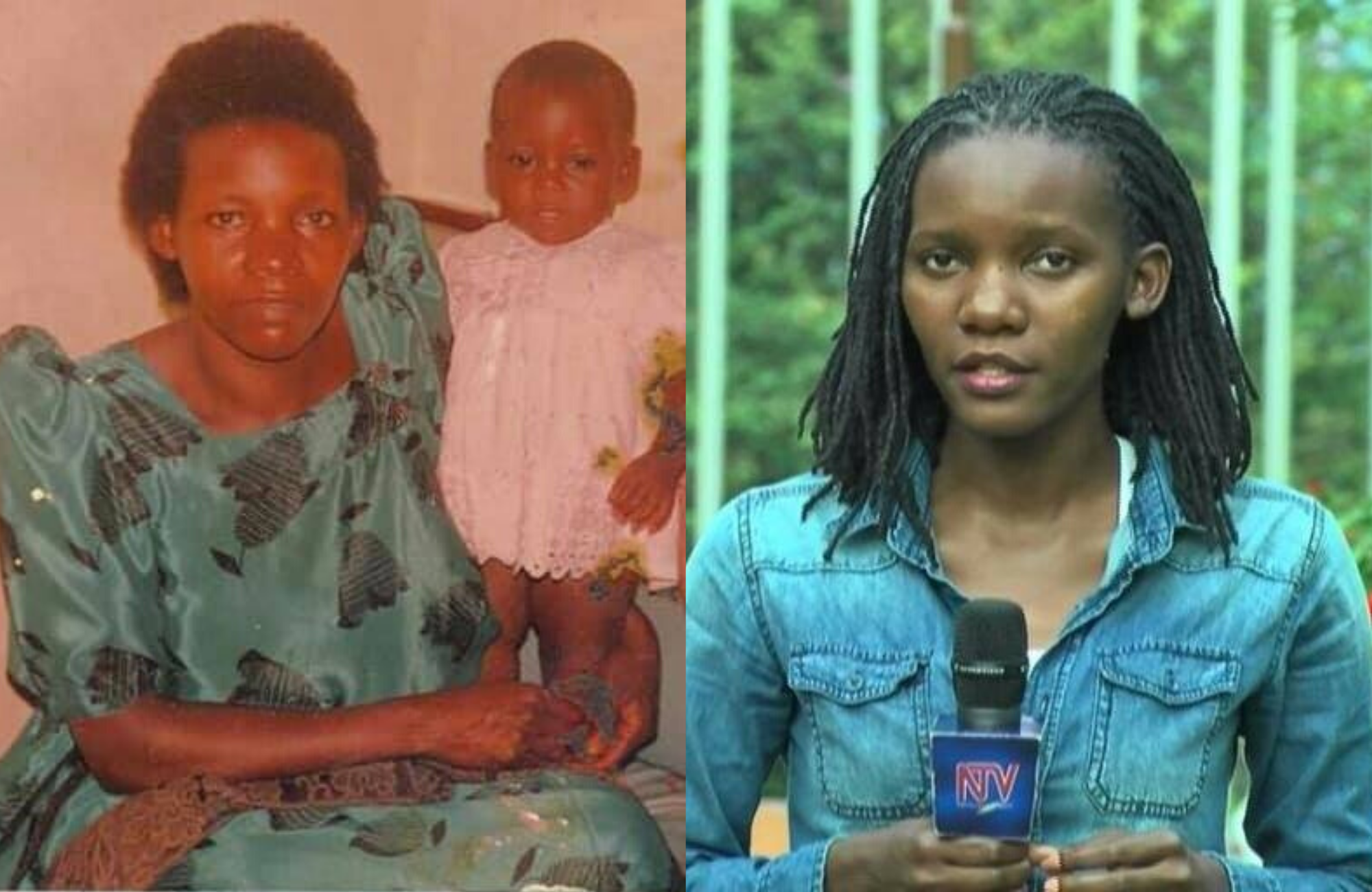

Population Matters’ Campaigns and Projects Officer, Florence Blondel, reflects on her family life in Uganda, and the changes she sees coming.

There was a time when I would start to count my siblings mentally and this would be accompanied by the use of my fingers (as I cracked the knuckles – a painful pleasure which irritates my husband on occasion). I come from a family of … yes, I always have to think of the number. You see, my father was not only cohabiting with my mother with whom he had seven children, but there were also multiple other women. All bore him children, with the ‘family’ suspecting one or two not to be his. His father, who had more wives and 45 children, could have inspired my father. Moreover, I was told that my mother had twins before meeting him. I can categorically state that my mother, whose thankfully earned farming income contributed to our education, spent most of her short life on Earth bearing children at short intervals.

A country full of children

I am from Uganda, a beautiful but poorly run and poverty-stricken country where about 78% of the population is under 30 years. Found in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) where the population is projected to double by 2050, Uganda is known for having one of the world’s highest maternal death, total fertility and population growth rates (PGR), the latter two partly driving the first. Indeed, the country’s latest National Population Policy acknowledges that Uganda’s high population growth “has been fuelled mainly by the persistently high fertility coupled with high but declining mortality”. Fertility is high because of:

- High unmet need for family planning

- Low modern contraceptive use and discontinuation, mainly due to side effects

- Large desired family size of 5.4 children for men and 4.8 for women

- High teenage pregnancy

- Male sex preference by couples/society

- Low median age at marriage & childbearing

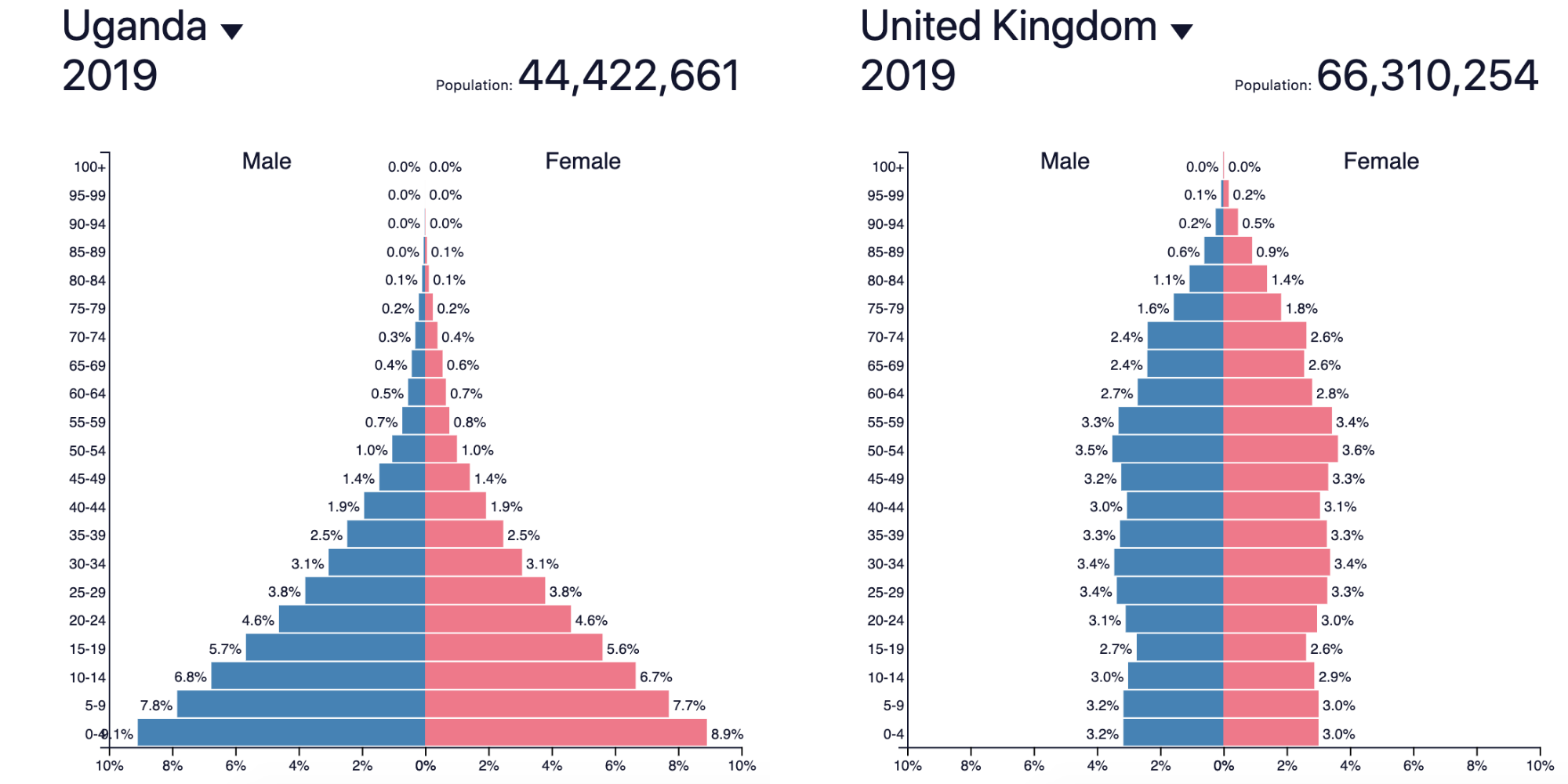

When my mother had her ninth and last child in 1990, a Ugandan woman on average was having about 7 children. Each year about 1.3 million Ugandans are added onto the population and the pyramids below tell a great deal about the country’s age structure (for comparison, I’m using the UK where I now live). I understand why, when my French husband visited the country for the first time in 2018, he was shocked by the number of children he saw everywhere – to me it was a common sight, as almost half of the population is under 15. These young people (all potential parents) put pressure on the already scanty education and health services in the country, and the environment is not spared either, as 98% of the general population uses wood fuel (goodbye forests).

At the current 3% PGR, without effective intervention, it will take Uganda about 23 years to double its current population compared to the UK’s 0.6% rate which may double its numbers in 116 years.

In 1990, the UK’s population was at 57 million people while Uganda was 17 million – 29 years later and the UK has added only 9 million more people, while Uganda has added 27 million. Of course, the UK like most European countries already had a head start during the industrial revolution and it gives me hope because pre those days, frequent childbearing was the norm and women had low power of autonomy.

My journey

My family background, as well as the historical treatment of women rooted in culture and religion, somewhat explains why I have no biological child yet, despite being from a country where childbearing starts in the earliest of teenage years and marriage means children, mostly. It’s been my protest. It is why as a journalist, I reported extensively on sexual and reproductive health and rights, social injustice, environment and development issues. It is also why I pursued a Master’s at the London School of Economics in Population and Development, and why I now work with Population Matters.

Women’s Agency: Change is coming

My mother gave birth to her last-born, my sister at 38 years, and 4 years later, at just 42 years, she died. My oldest sister at 41 has three and the youngest, two, while at 35, I enjoy being an aunt.

In Uganda, like the rest of Sub-Saharan Africa, pressures for women to be child-bearers do persist, but education (although with high dropout rates and poor quality) is paying off with more young girls and women embracing the agency that has been denied them for decades.

More marry and have children at later ages and even choose to have smaller families. I believe that, alongside other social changes including mortality reduction, if more girls and women have access to education and stay longer in school, have proper comprehensive sexuality education (including knowledge of existing modern contraception), and have more job opportunities, it is possible that Uganda may easily have a turnaround. In Bangladesh, fertility fell from 6.1 to 3.4 children per woman between 1980 and 1996 – just 16 years – with no coercive government family planning programme and a paltry per capita GDP of just $270. The initiative was purely voluntary and ethical, and now they are prioritising girls’ education, with the goal of reaching ‘replacement level’ fertility of 2.1 children per woman.

Hopefully, in the future, there will be no more children who have to crack their knuckles trying to figure out how many siblings they have, or wonder where each is, because fertility nearing replacement level is possible in my country. With the right policy measures, the long term effects of high population growth can be mitigated, because certainly, a slower population growth rate would have positive social and economic benefits, especially for young girls and women who have always been left behind.