A job or a child: India’s coercive population policies

While many people associate “population control” with preventing people from having children, our Gilead Watch campaign exposes how some countries and politicians are restricting – or seeking to restrict – their citizens’ reproductive freedom in order to promote a higher birth rate, to address fears about population decline. While coercive policies intending to reduce population are now rare, they have not gone away. Last year we reported on some disturbing proposals in Uttar Pradesh in India. We have since commissioned Indian gender and reproductive rights campaigner Debanjana Choudhury to investigate the situation. Here she outlines her findings, based on news stories, information in the public domain and discussions with experts on population and existing policies.

In 1952, five years after Independence, India became one of the first countries to initiate a national family planning programme. A decade later, this would become the largest government-sponsored family planning program in the world. Over the next two decades, with economic development falling short of expectations, more and more resources and attention were devoted to family planning.

In the 1960s, the government introduced new modern contraceptive methods and adopted a targets-based approach.

A dark chapter

The period of 1975-77 is remembered as one of the darkest chapters in Indian history. On June 26th 1975, the then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi proclaimed a national Emergency in face of growing economic crises and rising opposition. The resulting authoritarian rule imposed a repressive family planning program of forced sterilisations. In popular memory, the two years of Emergency have become synonymous with forced sterilisations. It has been estimated that in 1976 alone, around 6.2 million men were sterilised and over 2,000 men died in botched operations during this period. Furthermore, the period of emergency showed decisive shifts towards coercion and a deliberate targeting of marginalised and poor sections of society, particularly Muslim and tribal groups. Rebecca Jane Williams and other scholars have noted how poverty eradication remained a dominant theme of the 1970s. In Williams’ words, the electoral agenda of garibi hatao (remove poverty) soon translated into garib hatao (remove the poor).

Overtly coercive official policies were ended by the 1980s, with the two-child family norm advanced through the ‘Hum Do Humaare Do’ mass campaign.

In 1994, India was a signatory to the International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) held in Cairo, which concurred that population stabilisation could be achieved by addressing the education and literacy levels. Finally, in April 1996, the targets-based approach was abandoned and substituted by a decentralised approach with a focus on community needs and health rather than demography. The National Rural Health Mission (NRHM), introduced in 2005, strongly link the voluntary family programme with adolescent, maternal, and child health. The National Planning Policy (NPP) 2000 laid down meeting the unmet need for family planning as its immediate objective and stabilising the population as its long-term goal. To achieve this, the Government pioneered the ‘cafeteria approach’ to contraception that attempted to offer the public an expanded choice of contraceptives. This framework has since dominated family planning in India.

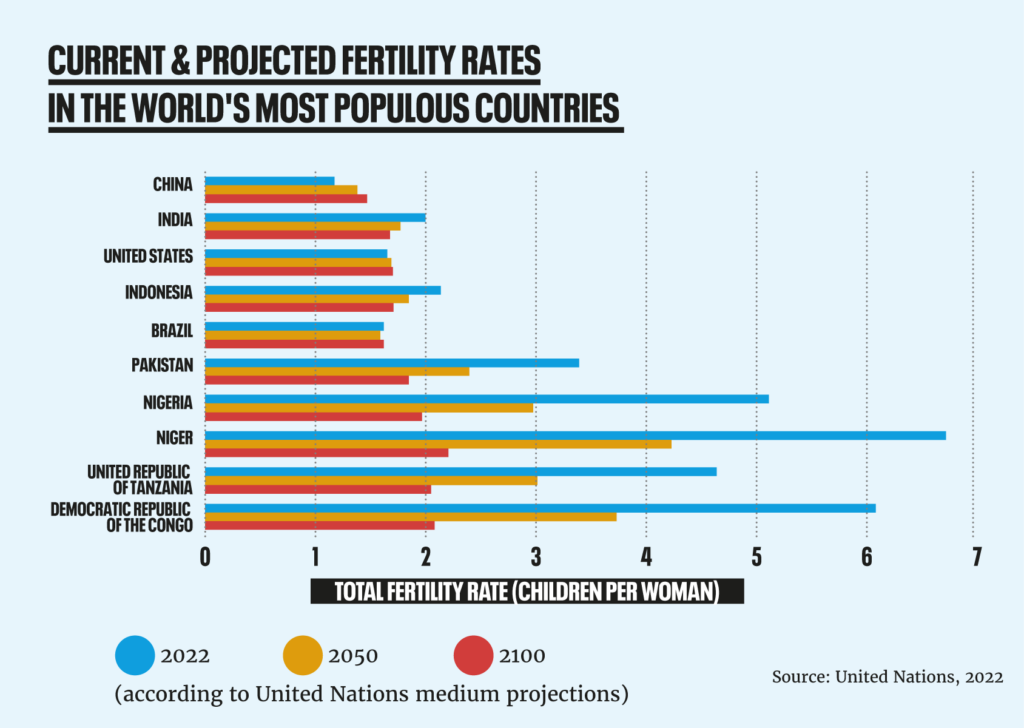

Today, while there are some significant regional variations, India has a Total Fertility Rate (the metric used by researchers to measure family size) of just 2.0 – this is below the global average and below the “replacement rate” at which a population stabilises and no longer grows or shrinks. India is continuing to grow, and will shortly surpass China to become the world’s most populous country, because of increased longevity and the large proportion of people of childbearing age, but is currently projected to peak (at nearly 1.7bn – approximately 270 million more people than today) and begin to decline in the 2060s.

The hidden coercion

Despite this overall progress towards an effective and rights-based family planning policy, however, India’s federal system allows states to adopt their own legislation and policies. In a number of them, the horrific coercive policies of forced sterilisation have mutated into a subtler form of coercion: you can have as many children as you like, but the authorities will limit your options and civil rights if you have more than two.

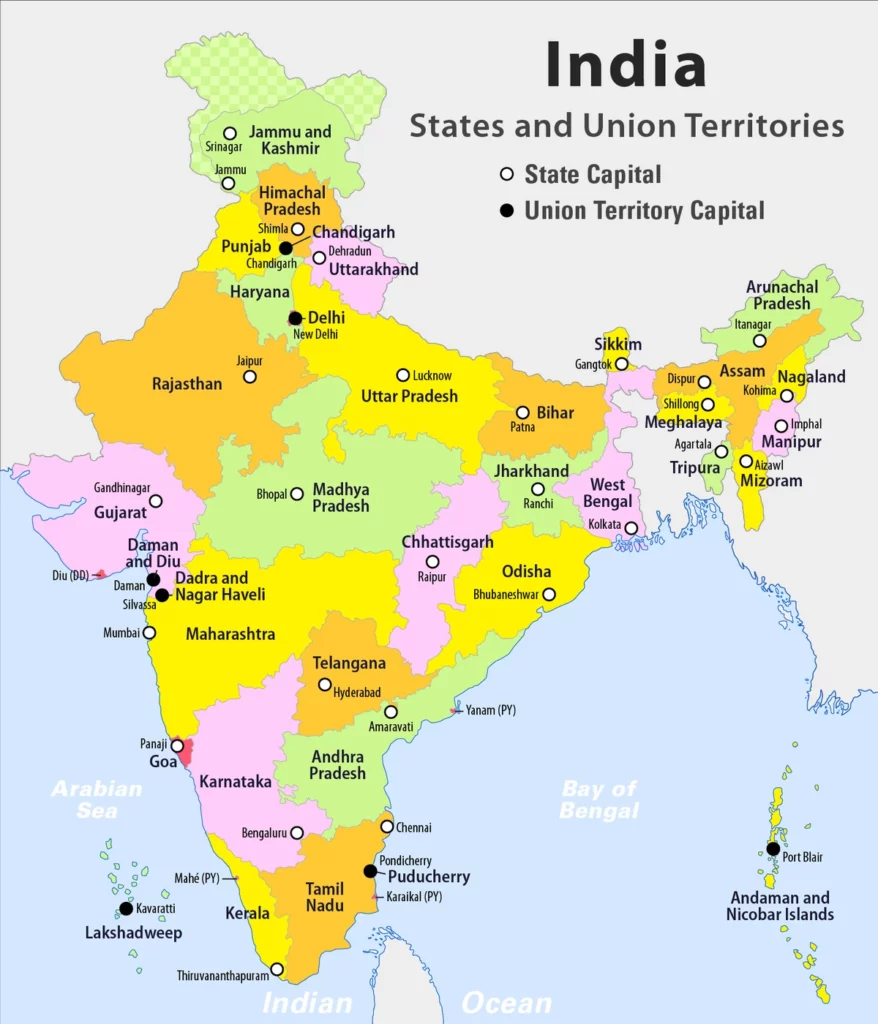

Since Independence, more than 35 two-child policy bills have been tabled in the Parliament; the most recent bill was Uttar Pradesh’s Population (Control, Stabilisation and Welfare) Bill, 2021. All such bills offer incentives for those abiding by the policy and penalties for those violating Many states including Assam (2017), Gujarat (2005), Maharashtra (2003), Odisha (1993), Rajasthan (1992), Uttarakhand (2002), Telangana and Andhra Pradesh (1994), already have some form of the two-child norm in place that determines eligibility for contesting elections or entering government service. The states of Chhattisgarh, Himachal Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, and Haryana have rescinded the two-child norms that they had earlier adopted (so the two-child policy has crept into the fabric of society, with many states adopting it in a clandestine manner).

- In Andhra Pradesh and Telangana a person with more than two children shall be disqualified from contesting an election.

- In Assam, the government ordered that individuals with more than two children would be ineligible for appointment in any services and posts under the state government after Jan 1, 2021.

- In Gujarat (Prime Minister Modi’s home state) anyone with more than two children is disqualified from contesting elections for bodies of local self-governance — panchayats, municipalities and municipal corporations.

- Maharashtra disqualifies people who have more than two children from contesting local body elections (gram panchayats to municipal corporations). The Maharashtra Civil Services (Declaration of Small Family) Rules, 2005 states that a person having more than two children is disqualified from holding a post in the state government. Women with more than two children are also not allowed to benefit from the Public Distribution System.

- In Odisha, individuals with more than two children are barred from holding any post in panchayats and urban local bodies.

- In Rajasthan, candidates who have more than two children are not eligible for government jobs, and are disqualified from contesting election as a village head or a member.

- In Uttarakahand, an amendment to the law passed as recently as 2019, bars individuals with more than two children from contesting Panchayat elections.

The two-child norms enacted in Madhya Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh and Rajasthan in the 1990s are based on the premise that elected officials would serve as “role models” for their constituents and inspire them to adopt a smaller family. There is no evidence to suggest that this has had the intended outcome.

These policies are not simply legacies of a less enlightened time, however. Uttar Pradesh has seen a run of recent proposals for punitive two-child policies. The Population Control Bill 2019, which proposed that couples with more than two children policy be made ineligible for government jobs and subsidies on various facilities and goods provided by the government, was later withdrawn – but replaced with the Population (Control, Stabilization and Welfare) Bill in 2021.

The 2021 bill proposed incentivising a two-child family size with housing subsidies, soft loans for constructing or purchasing a house, tax rebates, increased pensions, and free health care facilities. For those who did not comply, however, it proposed they should be barred from accessing other government-sponsored welfare schemes, contesting local elections, applying to government jobs, and, most shockingly, have limited access to food rations.

While the Uttar Pradesh bills are the only ones laid before legislatures recently, they sparked conversations in other states such as Karnataka and Uttarakhand about introducing similar measures.

The disincentives proposed by the Uttar Pradesh bill – and already implemented in whole or part in other states – have a direct impact on an individual’s livelihood and prospects. They restrict an individual’s choice and exploit their economic vulnerability and career aspirations in the name of ‘population stabilisation’. The bill not only undermines their reproductive rights, bodily autonomy (upheld by the court and Article 21 of the constitution) but its penal clauses are also in conflict with other fundamental human rights and constitutional rights (for example, Article 16 ensures equal opportunity in matters of public employment).

Do they work?

These coercive policies not only abuse individuals’ rights but fail to achieve their intended goals. No evidence has demonstrated their effectiveness. Studies have shown that the correlation between fertility rates and coercive measures is not substantiated. A 2005 study on the two-child norm in panchayats (village-level governance) in five states recorded unintended consequences of such clauses—desertion of wives, sex-selection and termination of female foetuses, and the resignation of posts followed by repeated pregnancies in the hope of a son! In a society where son preference is so prevalent, the two-child policy is widening the sex ratio at birth.

The study also found that restrictive policies were selectively applied, made little difference in contraceptive uptake, and had adverse consequences.

A two-child policy in India would have grave humanitarian and ethical consequences. Poonam Muttreja, Executive Director, Population Foundation of India, noted that two-child norms are known to “disproportionately impact the most deprived and vulnerable, particularly women and girls, who already have little to no access to health and education”. Women bear the brunt of population control policies. The actions proposed by the Uttar Pradesh draft bill, for example, would worsen gender inequalities. Muttreja noted that many of the incentives proposed in the bill (maternity leave, additional social security benefits etc.) would hold no significance for 80% of the female workforce who are employed in the informal sector.

Disproportionate contraception burden on women

India’s current contraceptive uptake is heavily reliant on female sterilisations. The perception that family planning and contraception are a women’s burden to bear is pervasive across both rural and urban areas. National Family Health Survey 5 (NFHS-5)—a recent nationwide survey from 2019 to 2021—found that only one in ten men use condoms and male sterilisations account for only 0.3% of all family planning methods. The onus of contraception has almost entirely fallen on women and female sterilisation has become the most opted method of contraception over the last few decades.

In an effort to promote birth-spacing methods and move towards a healthier method mix, the Government of India has tried to increase the basket of contraceptive choices in the last two decades. Nevertheless, the lack of awareness and misconceptions around male sterilisations and intrauterine contraceptive devices have done little to make the contraceptive burden more gender equitable. Recently, as Madhya Pradesh was falling short of its ‘targets’, a circular threatening the employees with loss of salary or forced retirement was circulated by the state officials. The document raised a furore and was quickly withdrawn.

The political and ethnic subtext

The debates on two-child norm have often taken a communal angle. Despite no analysis to back it up, many right-wing groups argue that Muslims will outnumber Hindus in the near future if their reproductive practices are not kept in check.

Currently, Muslims constitute only 14 per cent of the population whereas Hindus account for 80%. S. Y. Quraishi, former Chief Election Commissioner of India, writes, “NFHS-5 data shows literacy and delivery of services, not religion, influences fertility”. On the topic of a one/two-child policy, Dr Kalpana Apte, Director General, FPA India, commented that “one of the biggest myths that need to be busted is that family size depends on religion.”

The recent push for restrictive two-child policies principally originates from the political right, and has an implicit, and sometimes explicit, social agenda. The recent proposals in Uttar Pradesh and Assam were drafted under BJP-led state governments. On Uttar Pradesh’s population, Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath announced:

“Yeh prayas bhi kiya jayega ki vibhinn samudayon ke madhya jansankhya ka santulan bana rahe.”

(“An effort will also be made to maintain a balance in the populations of various communities.”)

Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh is a right-wing, Hindu nationalist pressure group. In Uttarakhand, the Chief Minister was persuaded to launch a population initiative after lobbying from RSS affiliates calling on the state government to ensure “demographic balance” (in other words, perceived rising numbers of certain segments of the population). Leaders and spokespersons in Karnataka have also voiced on curbing population basis certain criteria.

There have been several BJP leaders that have spoken that have elaborated on a perceived threat of a rising Muslim population. In 2021, RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat advocated for several measures to tackle this threat including the implementation of a population policy for a “religion-based population balance”.

Population and justice

These policies undermine reproductive freedom of choice, exacerbate gender inequality, and in a country with considerable socio-cultural barriers to abortion and misconceptions about its legality, will increase the number of forced sterilisations and unsafe abortions. They rob an individual’s agency and bodily autonomy and the punitive measures enforced in cases of non-compliance make it discriminatory and undemocratic.

The freedom to have a family, and to decide the size of your family, is established in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and should never be violated. A no less fundamental right is to be able to make that choice, through having the services needed to exercise it, including contraception, abortion and comprehensive sexuality education. Exercising that choice, especially for the most vulnerable in society, must also mean freedom from punishment and disadvantage from those in power for making choices different to those they want you to.

Governments concerned about population must take the positive steps that respect rights and improve people’s lives, and that are shown to work: ensure everyone can access family planning services, alleviate poverty, provide the highest standards of child and maternal health, ensure everyone is able to go through school, and establish true gender equality. The two-child policies in Indian states must be ended.

(Full list of references available on request.)