Is population growth yesterday’s problem?

At Population Matters, we’re often told that population growth is no longer a concern and, much worse, those, like us, who talk about it are racist and being “anti-human”. Our Communications Officer, Florence Blondel has this response.

It’s hard to dismiss population growth as yesterday’s problem when you live in a country where the population growth rate is above 3% annually, translating into 1.2 million babies; where on average a woman has more than five children; where almost 80% of the population is under 30 years old; where women are exhausted from popping out babies almost annually; where an overburdened health system can’t prioritise them and maternal deaths become normalised; where the destiny of some young girls is child marriage; where GDP per capita is a paltry $850. That’s my home country, Uganda, and these are the things I experienced personally and reported on as a journalist there.

The Uncomfortable Truth

Uganda, currently made up of about 44 million people, has the world’s youngest age structure and is expected to double in size by 2050, as will most high low-income nations in Africa, Sub-Saharan Africa. We have been struggling for all of my life and I’m about to turn 40. Things have a way of staying the same, and citizens are resigned to existing with the barest minimum of what our institutions offer us. Ending and reversing our population growth through ethical means would give us a far better chance of changing that, and we want it.

Very recently, the UK journalist and commentator Dominic Lawson poured scorn on those concerned about population in his Sunday Times article, The anti-humans are simply wrong, as ever. His targets included (not for the first time) us, here at Population Matters. He was born in a country where women on average have about 1.5 children, where most have agency and can easily access modern contraceptives, have far fewer barriers to getting a quality education and employment, can call out their politicians without their voices getting squashed, can bleed with dignity and won’t be sold into marriage at the first sign of a period so that the parents can get a goat, cow or a bar of soap to take care of other siblings. I’m lucky – yes, it’s down to luck for most of us over there – to have thrived and succeeded.

As one of many privileged people living in high-income countries, Mr Lawson appears to care more about the supposed threat of low fertility to affluence than the reality of high fertility and deprivation. When you are in such a country and have witnessed this trend across all the regions, things look different. You might want to help give agency to the young girls and women who seek it – the ones contributing to that growth. The ones whose tired uteri are wilfully disassociated from population growth by those weeping over declining birth rates.

Mr Lawson closes his article by explicitly linking population concern with racism. But no, if you advocate for population concern you (we) are not racist or anti-human. You are motivated by concern for the well-being of people here on Earth, today and in the future. Dominic Lawson should stop using his platform to belittle the efforts of activists who are trying to ensure others have what the UK achieved many decades ago.

A reality check

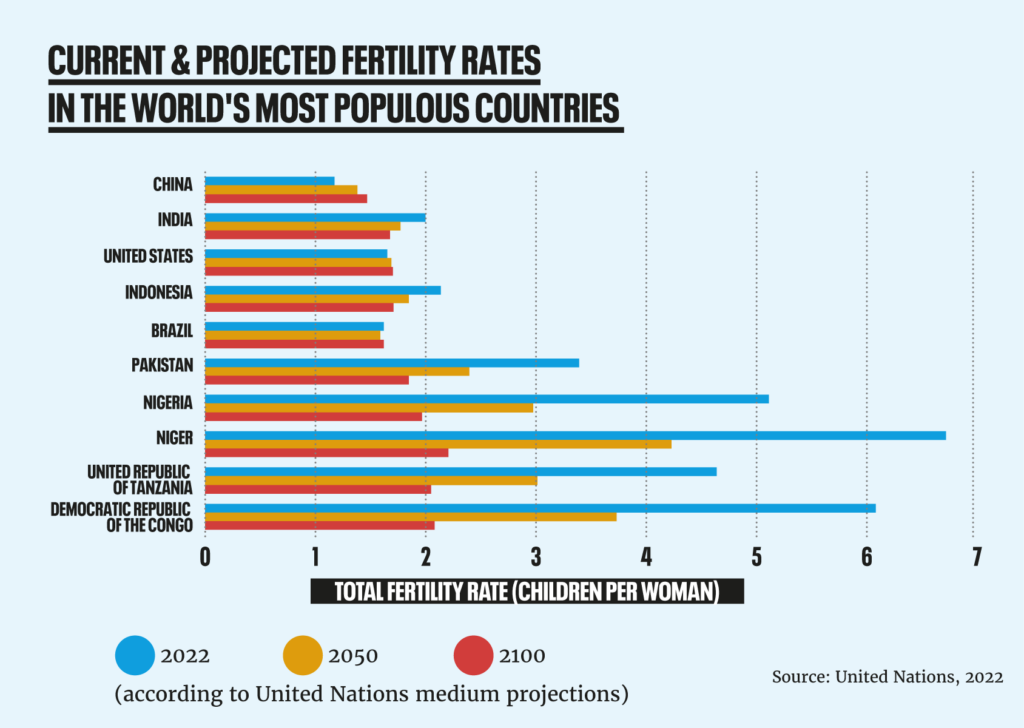

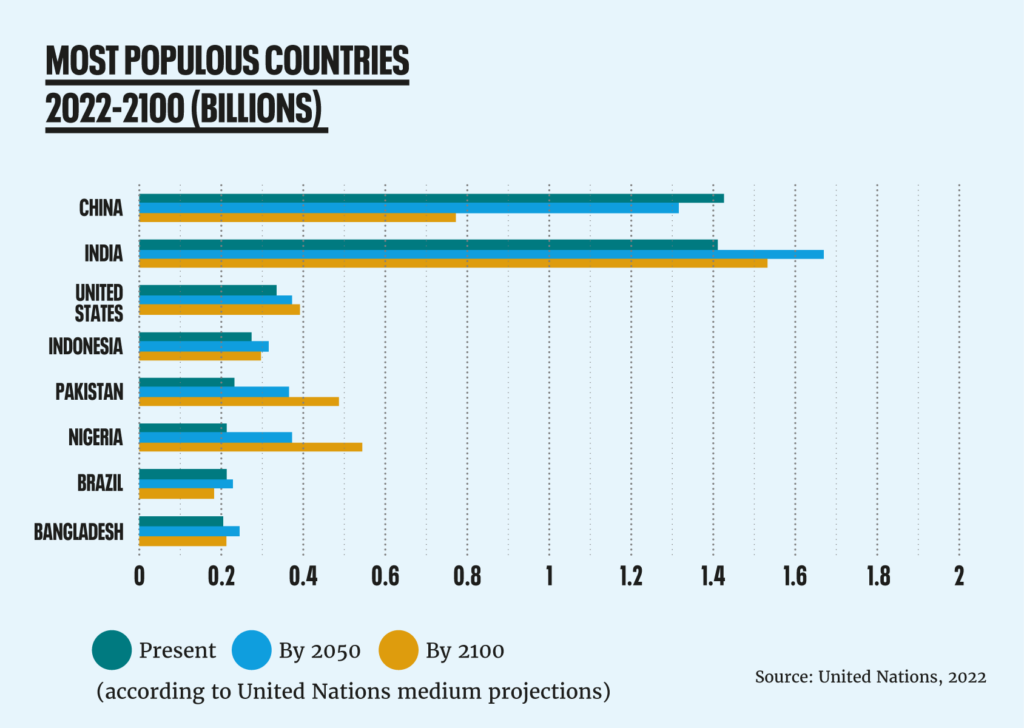

The fact is that we still live in a world of staggering population growth – another 1.7 billion of us in the next thirty years, according to the UN. Most of the increase in the world’s population will occur in the poorest countries, many of which are in Africa. In his article, Mr Lawson, like many critics of the population concern case, resorted to the tired ploy of citing Thomas Malthus’ famous 224-year-old pamphlet, An essay on the principle of population, as proof that current population concern is misguided. He and they need instead to turn their attention to today’s reality: hundreds of millions of women in low- and middle-income countries who want to have smaller families but cannot because of poverty, patriarchy and hopelessly inadequate health and family planning provision.

The “baby bust”

The trigger for Dominic Lawson’s piece was the recent news that China’s population has started to fall. That is neither a surprise or a disaster, as Population Matters’ statement on it made clear. China’s demographic trajectory poses some genuine challenges, but none that cannot be met.

Meanwhile, our planet is already paying a heavy price for China’s pursuit of economic growth and the size of its population. It has the highest greenhouse gas emissions of any country in the world. As Population Matters wrote:

A smaller, stabilising Chinese population should be celebrated for helping to curb climate change, reduce pollution and improve human well-being – not least, that of its own people.”

The “baby bust” narrative not only turns a blind eye to the grim reality of life in low-income, high-fertility countries, but it also ignores other critical realities. Globally, having fewer of us is good for humans and other creatures with whom we share the planet. The latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report, published in April 2022, unequivocally stated:

“Globally, Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita and population growth remained the strongest drivers of CO2 emissions from fossil fuel combustion in the last decade.”

Population growth is a driver of critical environmental and resource challenges and is incompatible with planetary health and long-term sustainability. The impact on the environment is felt through agricultural expansion, deforestation, biodiversity reduction, and water resource stress. Of course, so much of that is driven by high-income countries, where a sea change in consumption is needed, as well as a commitment to redress the historical and current injustices that contribute to the drivers of population growth in countries like mine. And where, given that one British citizen is responsible for 40 times the carbon emissions of a Ugandan citizen, the size of population, and exercising the choice to have a small family, is vital too.

The solutions are clear

These are the things we can and must do to address population growth, and because they fundamentally improve lives:

- Empower women and girls

- Remove barriers to contraception

- Offer quality education for all and ensure girls stay longer in school

- Fight for global justice and sustainable economies

- Exercise the choice to have smaller families, especially in high-income countries

I’m a living testimony – at least to the part where those solutions – not as scaled widely as they should be, sadly – have seen me thrive as a girl and woman. A woman who has now been able to choose a small family. The world is not going to end any time soon because girls and women especially in low-income countries will get an opportunity to control their bodies and not be reduced to child bearers and rearers!