Solutions

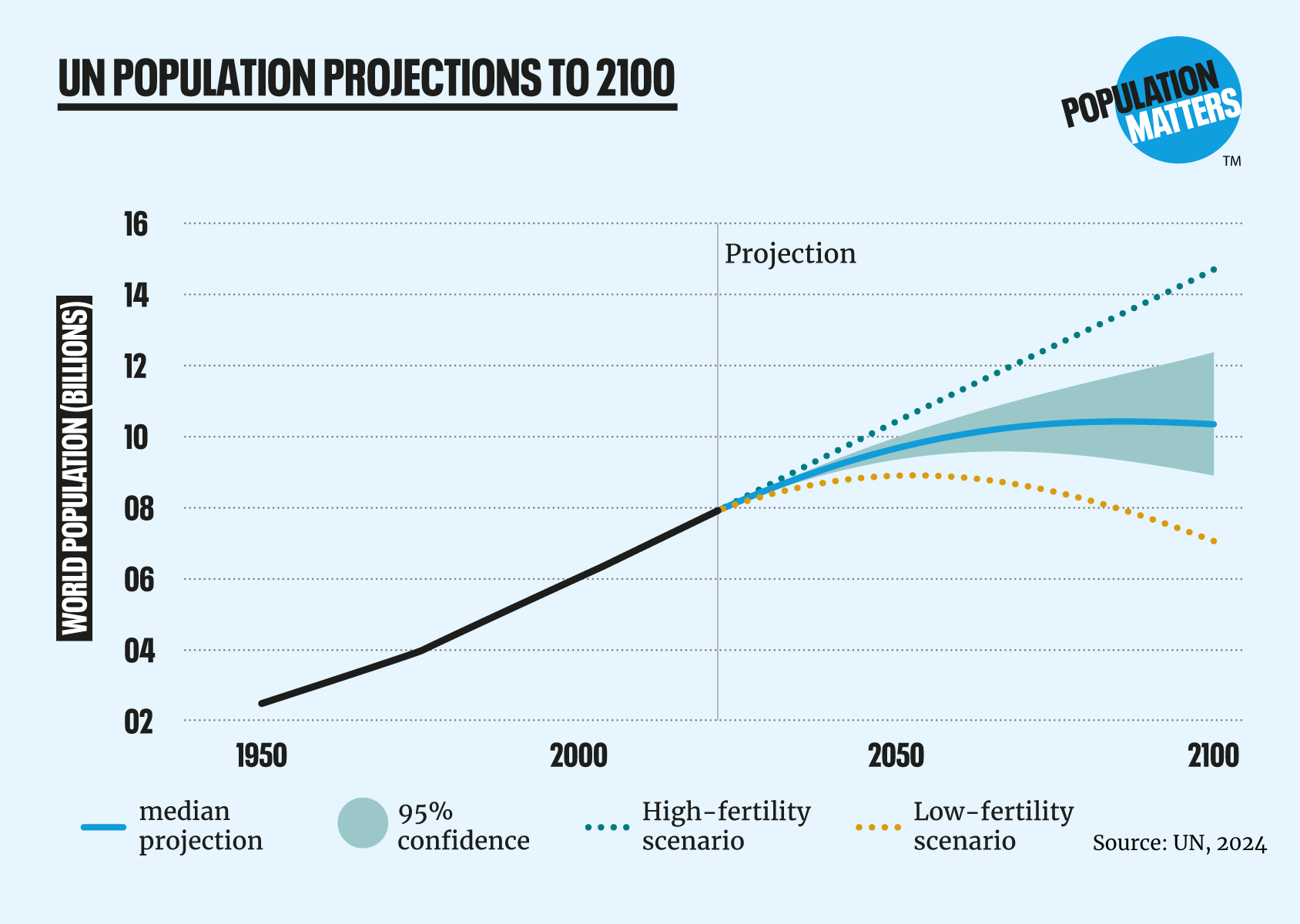

Although population growth in the 20th and 21st centuries has significantly increased, it can be slowed, stopped and reversed through actions which enhance global justice and improve people’s lives. Under the United Nations’ most optimistic scenario, a sustainable reduction in the world’s population could happen within decades.

We need to take many actions to reduce the impact of those of us already here – especially the richest of us who have the largest environmental impact – including through reducing consumption to sustainable levels, and systemic economic changes.

a world of 10 billion?

The United Nations makes a range of projections for future population growth, based on assumptions about how long people will live, what the fertility rate will be in different countries and how many people of childbearing age there will be. Its main population prediction is in the middle of that range – 8.5bn in 2030 and 10.3bn in the 2080s.

Positive people-focused policies

Many countries have had success in reducing their birth rates through policies which improved lives and empowered people.

Thailand, for instance, reduced its fertility rate (the average number of children per woman) by nearly 75% in just two generations with a targeted, creative and ethical population programme, which helped it to grow economically.

In the last ten years alone, fertility rates in Asia have dropped by nearly 10%.

1) Empowering women and girls

Where women and girls are empowered to choose what happens to their bodies and lives, fertility rates plummet. Empowerment means freedom to pursue education and a career, economic independence, easy access to sexual and reproductive health services, and ending horrific injustices like child marriage and gender-based violence. Overall, advancing the rights of women and girls is one of the most powerful solutions to our greatest environmental issues and social crises. Solutions 2 and 3 below are both tightly linked with female empowerment.

2) Removing barriers to contraception

Nearly half of all pregnancies are unintended. Currently, more than 200 million women who want to avoid pregnancy are not using modern contraception. There are a variety of reasons for this, including lack of access, concerns about side effects and social pressure (often from male partners) not to use it.

These women mostly live in some of the world’s poorest countries, where population is set to rise by 3 billion by 2100. Overseas aid support for family planning is essential – both ensuring levels are high enough and that delivery of service is effective and goes hand-in-hand with advancing gender equality and engaging men.

Across the world, some people choose not to use contraception because they are influenced by assumptions, practices and pressures within their nations or communities. In some places, very large family sizes are considered desirable; in others, the use of contraception is discouraged or forbidden.

Work with women and men to change attitudes towards contraception and family size has formed a key part of successful family planning programmes. Religious barriers may also be overturned or sidelined. In Iran in the 1980s, a very successful family planning campaign was initiated when the country’s religious leader declared the use of contraception was consistent with Islamic belief. In Europe, some predominantly Catholic countries such as Portugal and Italy have some of the lowest fertility rates.

3) Quality education for all

Ensuring every child receives a quality education is one of the most effective levers for sustainable development. Many kids in developing countries are out of school, with girls affected more than boys due to gender inequality. Access to education opens doors and provides disadvantaged kids and young people with a “way out”. There is a direct correlation between the number of years a woman spends in education and how many children she ends up having.

According to one study, African women with no education have, on average, 5.4 children; women who have completed secondary school have 2.7 and those who have a college education have 2.2. When women are able to exercise their reproductive rights, they are empowered to gain education, take work and improve their economic opportunities.

A UN survey showed that the more educated respondents were, the more likely they were to believe that there is a climate emergency. This means that higher levels of education lead to the election of politicians with stronger environmental policy agendas.

4) Global justice and sustainable economies

The UN projects that population growth over the next century will be driven by the world’s very poorest countries. Escaping poverty is not just a fundamental human right but a vital way to bring birth rates down. The solutions above all help to decrease poverty. International aid, fair trade and global justice are all tools to help bring global population back to sustainable levels. A more equal distribution of resources and transitioning away from our damaging growth-dependent economic systems are key to a better future for people and planet.

5) improving child and maternal health

Where children do not survive into adulthood, people tend to have larger families. Reducing infant and child mortality has been key to bringing birth rates down across the world. Family planning and gender equality help to achieve that, by allowing women to start having children when they are older and increase spacing between children. As family size goes down, that also allows greater investment in health services, especially in low-income countries.

6) REDUCE OUR CONSUMPTION

It’s important to remember that people in the rich parts of the world have a disproportionate impact on the global environment through our high level of consumption and greenhouse gas emissions – in the UK, for instance, each individual produces 70 times more carbon dioxide emissions than someone from Niger. When we understand the implications of our individual impact on the environment, we can take steps to reduce our own consumption of resources. The more of us that work collectively to reduce our consumption, the greater the impact we will have to reduce pressure on the environment and achieve a more sustainable world for all.

Join Us

Want to support our work towards a healthier, happier planet with a more sustainable human population that respects Earth’s limits?

Join us today!