A positive nuisance

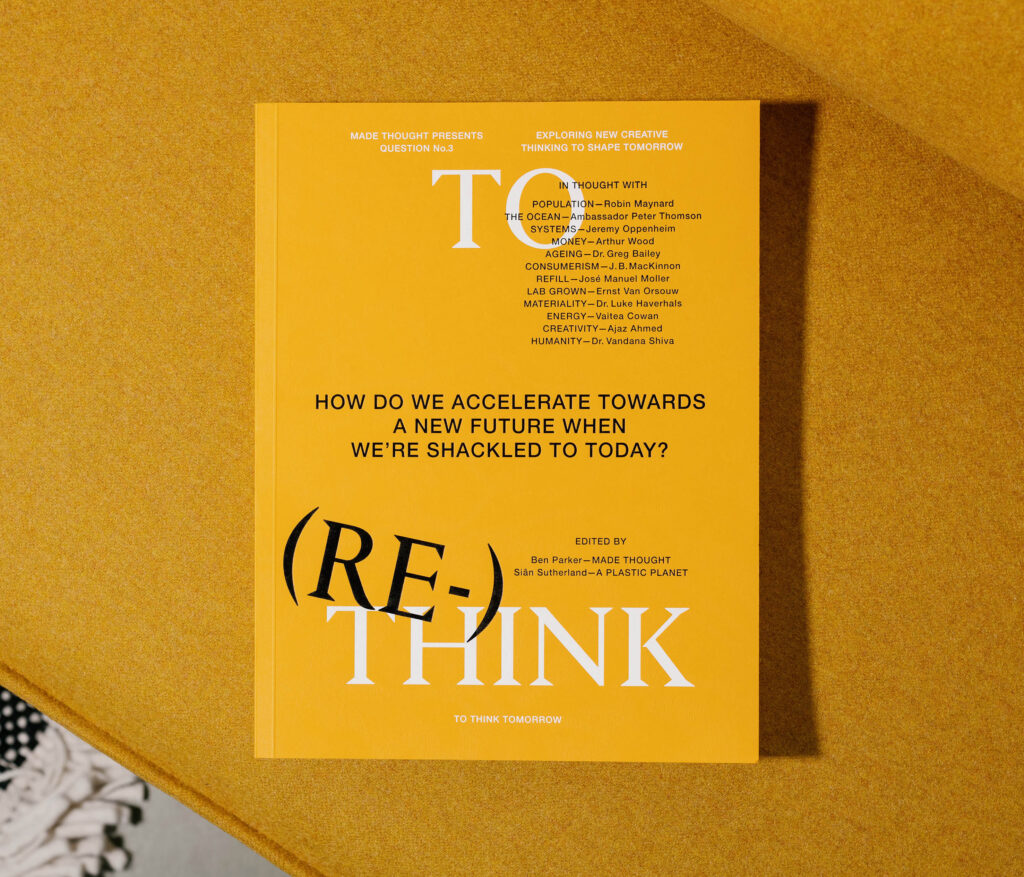

This September, our Executive Director, Robin Maynard, will be moving on to pastures new after leading the organisation for seven years. Here, we are posting a recent interview he did with creative agency Made Thought, for the latest issue of their journal To Think. The interview gives a real insight into Robin’s motivations and his deeply held passion for the natural world. As we prepare for a new chapter at PM, his words will help us focus on what’s important, what’s at stake and what we can do.

Made Thought:

As we become more experienced in the business of life, it’s easy to get into the habit of intellectual inertia. We can close our minds, becoming what we once ran from in our youth. A stagnation of thought begins to take hold and begins to cripple us.

Any organisation, or society, no matter how radical in its inception can fall victim to this same stagnation. That’s why moments of maverick thinking can be so fleetingly rare. But maverick thought doesn’t require a prophet-like zeal running through every moment of one’s life.

Maverick thinking is born from the smallest interactions, from those who are on the peripheries of power, from those not laden with prescribed expectation. To inject hope and passion into the smallest interactions of life is to practise this sometimes illusive maverick thought. Developing an everyday radicalism is the fusion from which maverick thought emerges, and from which change can occur.

ROBIN MAYNARD is that maverick. Robin describes what he has done over the past thirty years as making a “positive nuisance” of himself. Today, he acts as that model of everyday radicalism.

His current role, as Director of Population Matters, highlights how human population has grown beyond Earth’s sustainable means, where we are consuming more resources than our planet can regenerate. This effect creates devastating consequences; all exacerbated by our ever-increasing numbers. Global population is rising by more than 80 million a year and is most likely to continue rising for the rest of this century unless we take action. He believes at the heart of humankind’s malaise is our obsession with a perverted sense of growth— in consumption, materialism, and population.

Robin speaks eloquently about the importance of optimism in a world trapped in perpetual crisis. And he is hopeful that we can harness a new-found sense of optimism—one that is durable and at its very heart—truthful.

a positive nuisance

When I first started working as an environmentalist, I’d recently come back to the UK from teaching abroad, as an English graduate. I don’t have a zoology or a biology degree. I’ve had to learn on the hoof. I went into volunteer at Friends of the Earth, while I was looking for a teaching job. Then Chernobyl blew up changing everything.

Before then, Friends of the Earth, Greenpeace and most ecologists were still regarded as ‘hopeless hippies’. I began working on farming issues, and used to turn up to talk at farmers’ groups about pesticides, and organic farming—and they were expecting, I’d say hoping, for some long-haired dude in an Afghan coat to turn up and take the piss out of. But against those preconceptions, we found more common ground.

The way I describe what I do, was gifted to me by an elderly lady I met during the Newbury Bypass campaign way back. I watched her walking towards the police lines and the security guards, who were stopping everybody. She walked right up to them and past them without missing a step and they didn’t know what to do.

I went to talk to her afterwards and told her how impressed I was by her bravery. Her response stuck with me, “Well, I’ve always made a positive nuisance of myself”— such a wonderful description. So for the past 30 years, I’ve tried to follow her example, to make a positive nuisance of myself to those who don’t want to change or let go their control of the world.

A lot of things have changed in the three decades since—if not enough. Most worryingly, some environmental organisations themselves haven’t changed—but got stuck in a rut. Competing for funding, conforming to head office mentality.

Reacting to that, there’s a lot of incredible, fresh energy from the likes of Extinction Rebellion, doing things differently. They’ve stirred things up and aren’t afraid to challenge the system. The irony of Greenpeace’s offices being occupied by Extinction Rebellion is so delicious. Once the radical guys, now today’s radicals are marching to their office and saying you’re stuffy and standing in the way.

HEAD OVER HEELS WITH NATURE

When I was about eleven years-old, I was given a book written by the pioneering biologist Rachel Carson, called The Sea Around Us. It’s a wonderful book about our oceans, how they function, what lives in them. It really opened my mind to the complexity of life on Earth. It had these incredible illustrations. I remember one in particular of a giant squid fighting off a sperm whale, thousands of feet down inthe abyss. It really stimulated my love of the natural world.

Much later, I came across her darker book, Silent Spring, the one that launched the environment movement. The brilliant thing about Rachel Carson was she could inspire people with a love of nature, but not shy away from the darkness and the damage that humanity was doing— bluntly, that a male, dominating, approach to the natural world was doing.

I’d been made aware of the harm that industry can do by my father’s story. As a young man, growing up in the Potteries, he succumbed to asthma and the family doctor prescribed a stint in the countryside, to get some time away in fresh air—an early case of ‘nature prescribing’. He was sent away to a relative in Devon and got a job collecting wild plants for a herbalist; an outdoor classroom for learning all about wildflowers, butterflies, the natural world—its benefit to his health and indirectly for others. As a boy, we collected moths and butterflies together in the fields and woods near our home. He made these wonderful potions which would draw the moths down at night. But I distinctly remember, I guess it would have been in the mid-seventies, that we suddenly stopped. Unspoken. We just stopped. No need to state the obvious, there were far fewer of them around, even the ‘common’ ones. Innocence gone. Knowledge of good and evil.

A MOMENT TO THINK DIFFERENTLY

As a teenager, I was captivated by the news footage of Greenpeace ‘making waves’. Those men and women, wild haired, in their wetsuits in tiny dinghies putting themselves between the whales and harpooners. You look at those pictures now and of course, what you didn’t take in at the time, is that those guys were on their own in the middle of the ocean with maniacs firing grenade harpoons over and at them. Bravely and brilliantly, they brought that reality back to our living rooms and woke us up.

The whalers didn’t want the world to know that they were slaughtering these incredibly complex, sophisticated, intelligent animals to turn them into trivial things like lubricants for differentials in cars, flower pots and fertiliser. I wanted to do something like that. I didn’t quite have the guts at the time—I was still a teenager—but the seed was sown.

OUTRAGE AND OPTIMISM

If we are to turn things around, optimism is paramount. That’s the irony, because many people, especially old school economists, think environmentalists are a bunch of pessimists or worse—particularly in my area of environmentalism.

I work on the issue of human population, how many there are of us, as well as how much some of us are consuming. The stereotypes thrown at me and my colleagues are that we are ‘miserable old- Malthusians’, ‘misanthropes’, ‘hate children’ and worse. We don’t and aren’t. I’ve got two young daughters, and if I wasn’t an optimist, I couldn’t do this job.

Nobody working in the environmental field could do the job if they didn’t have a core of optimism, because the science is pretty overwhelming.

An observation by a journalist I know, made me think the game was changing:

“You know Robin, the stuff we’re getting from the scientists is far more alarming than what we’re getting from you environmentalists. It used to be the other way round.

The U.S. Special Presidential Envoy for Climate, John Kerry, summed it up at the time of COP26, “For 30 years the scientists have been telling us this—they’ve been telling us what’s to come and it’s happening—but it’s happening faster than we expected.” To humankind’s cost, we have largely ignored these scientists for decades.

But too much optimism can imperil us— be a bad thing. Politicians and too many in the media seem to think it’s going to be okay, and some tech-fix will emerge— brilliantly parodied in DiCaprio’s Don’t Look Up! It just isn’t if we carry on with business as usual.

Take deforestation, the ongoing human encroachment on formerly natural, wild areas. Covid, Ebola and Monkeypox are just a handful of the thousands of viruses and pathogens which are and can make their way out past the cordon sanitaire and buffer zones of forest, transitioning from being relatively harmless in their natural hosts and habitats to seriously harming us. We must be honest about the inconvenient truths, whilst holding to realistic optimism, if we are going to get out of this mess. That’s a deft line to tread.

Lost in Space

At present the ‘establishment’, the business and political elites, have other weird, warped, delusional priorities. Billionaires vie with each other to blast themselves on what it’s hard not to see as enormous mechanical phalluses into the void of space. An analogy aided by the fact they’re men of post reproductive age. Is this their last hurrah, thrusting themselves into space, for whose benefit other than to their egos and brands?

Not to diss all space exploration—it’s achieved some amazing things. Not least for the environment movement, giving us that picture and perspective to see our one and only living planet hanging like a blue green pearl in space, as yet still uniquely alive and able to support complex life. The fragility, and the beauty of it. It’s fascinating that almost all the astronauts, those most technical, logical and capable of people—have an almost spiritual Damascene moment when they look down and back upon their mother Earth, upon Gaia.

YOU CAN’T RELY ON ELITES

But the billionaires, what have they achieved? Zilch as far as I can see, other than to generate a lot of hot air and pollutants. They’re not focused on changing things for the better here on Earth for most people, because their fantasies are about new worlds, new frontiers and Dr Frankenstein shit about staving off their mortality. The super-rich are immured from the negative impacts of their growth and profit prioritising economic model. The elite can buy their way out and distance themselves from the problems they cause. I don’t think many of them are going to be the solution.

INSPIRATION FROM THE GLOBAL SOUTH

In contrast, the most inspiring of people that I’ve met over the years have been some of the poorest people in some of the most challenged parts of the world, making their own solutions.

I was privileged to meet community activists in the slums outside Nairobi during the 2019 International Conference on Population and Development. Kibra slum or ‘informal settlement’ is the biggest, not just in Kenya, but in Africa.

I was able to go there because I was with people who knew the place and the people who lived there—otherwise I’d have stood out like a sore thumb.

I met wonderful, inspiring people—young women—who wanted to change the future for their children, who wanted their daughters to have greater choice over their lives. And a group of young men previously involved in criminality, who’d turned over a new leaf after one of their friends had been lynched by vigilantes, who’d had enough of being robbed. They turned their story around. Setting up an environmental project in the slums, cleaning up the open sewers, planting community gardens, whilst also promoting family planning, choice, and women’s rights.

What amazed me was their energy, optimism and humour. They were great fun to be with—taking the mick out of me as an old white guy wandering about in their community not really knowing exactly what was going on. When I meet some of my green colleagues in the UK or Europe, they’re often very serious —understandably — a bit boring — less understandably — and don’t have that raw energy, which was so inspiring and humbling to see in those places, amongst those people and their circumstances.

TECHNOLOGICAL PARADOX

I’m a bit of a Luddite in terms of contending with IT. Not quite as extreme as Tyler Durden, the Brad Pitt character in Fight Club, who blew up all the computer servers to collapse the global financial system, with his romantic vision of smoke curling up from the campfires, as survivors return to a hunter-gatherer existence, cooking wild deer. A wonderful dystopian image, but I don’t go that far, because the internet has fundamentally changed things—for good and bad.

It has enabled us to communicate in ways we couldn’t imagine in our wildest dreams when I started at Friends of the Earth in the mid-1980s. It has enabled us to get and receive information from across the world in seconds. The web and the linked satellite technology allow us to see forest fires and deforestation in the Amazon down to the square meter. We can even listen into the forest. Technology decoding the complexities and connections of our extraordinary ecosystems, world-wide webs of woods, forests, oceans and fungi.

Perhaps one day we’ll be able to hear and understand what the natural world, flora and fauna, has been trying to tell us for so long.

SPACESHIP EARTH

Technology is a wonderful tool, but it can also be a delusional tool, distracting us from what’s really important in life, spending our days in a virtual world, whilst our only real one fragments. Those space cowboys, Bezos, Branson, Musk, spin yarns of new frontiers, of far off dead planets, of detonating nuclear devices to create an atmosphere, and terra-forming the desiccated surface into endless prairies of plenty.

But even if they could, where’s the spaceship for 8 billion people, let alone the ark for those millions of species, and the diversity that took billions of years to weave together our complex, organic and sustainable world?

THROW AWAY THE RULE BOOK

When I started out as a volunteer at Friends of the Earth, I was acutely conscious of my thin knowledge. But my boss at the time who was Head of Campaigns, Andrew Lees, a wonderfully inspirational man, said to me, “Robin, all you need is to remember this: How much do you really need to know to make a difference? Your job is not to be an encyclopaedia of agricultural botany and zoology. There are plenty of academics who have that knowledge, who you can tap into. Remember we’re on the side of good, we’re not trying to sell something, just trying to stop bad things happening—that’s enough. You won’t always get all the facts right, but you’re trying to make a positive difference.”

That’s stood by me. Yes, we need the experts, to get their knowledge out and to be heard. But another thing, I learned at Friends of the Earth, as we grew as an organisation with more resources, the basement filled up with all the reports, documents and briefings we could now produce. At the time I thought it was amazing but then I realised that if the evidence and facts were enough on their own, then Friends of the Earth and all the other conservation groups wouldn’t need to exist. People would’ve got it.

COMMUNICATION ELEVATES SCIENCE

The scientific facts of humankind’s descent into environmental crisis have been known for over 40 years.

But unless you can communicate them in a way that engages people, makes them want to change their lives and challenge others, the facts just collect dust in an archive. They have to be liberated, communicated, transformed into compelling images, to evoke instinctive, emotional responses. As Greenpeace did all those years ago. Writing about the whales, their decline, wasn’t enough. People had to be taken into the drama, the narrative, made to feel viscerally connected, responsible, have ownership, and be empowered to change things.

THE POWER OF STEWARDSHIP

That’s what I think true stewardship of this planet is about, empowering people to take ownership of their home and responsibility for their actions. More powerful and effective than any government diktat. Some years ago I was sent on assignment to Malaysia by the BBC to cover alleged sustainable logging operations. There was a stark dichotomy between what the Malaysian government officials labelled sustainable and how the forest communities lived and practised it in their everyday lives.

The forest people’s long-houses made from the forest’s resources were designed to be taken down every few years, to move and rest an area of land, allowing it to regenerate—the ultimate flat-pack which the people set-up in another part of the forest. It was simple genius—at one with the forest in a way that no government official could conceive. Unsurprisingly, the government saw such sustainability, resilience and independence as a threat to their power and control.

For me, it was a spiritual experience, seeing how those tribal people lived, in harmony with the forest and themselves. The roof space above every family’s living quarters, each set alongside each other in the long-house like so many terraced houses, was open and you could hear the whole community go to sleep and wake up—acting as an interconnected organism.

That gives me hope, as in some of the bio solutions that are emerging, based on connection and synergy, rather than separation. Where human beings and our activities are no longer represented atop a triangular apex with us ‘above’ and extracting from nature. But at the heart of nature, interconnected, inter- dependent, and in harmony with it, like those forest dwellers.

There was a great quote I recalled when thinking about the invaluable knowledge of indigenous people, which came from an account of a wildlife management talk in Canada. A tribal leader kept objecting to other delegates using the phrase ‘wildlife management’: “Wildlife manages itself. The only thing we need to manage is us”. He wouldn’t let it lie, sticking to his point and being that needed ‘positive nuisance’.

A PARADIGM SHIFT TO SMALLER FAMILIES

In step with the rapid decline of nature over the past three centuries has been the explosion in our human population and the increased consumption of the Earth’s resources—particularly, amongst those countries that industrialised first.

In my lifetime, the human population has more than doubled. Positive solutions, safe, affordable technologies are available— and nature-derived ones: condoms are made from latex, sustainably ‘tapped’ from rainforest rubber trees, the contraceptive pill was first developed in the 1950s thanks to Diosgenin, a plant steroid found in rhizomes of the wild Mexican yam.

Solutions that offer women choice and agency over their bodies, their fertility, as to when and how many children they have. In the developed world, women mostly—but not always and not everywhere—have access to safe, modern contraceptives and so that choice. With choice comes a responsibility, to use it and use it consciously—given that in the rich developed world each of us consumes far more resources and produces far more pollution per head than people in poorer, developing, low income countries.

Choosing a smaller family here in the UK, Europe, and the US is the most impactful eco-action any of us can take—far more so than giving up our cars, switching to a vegetarian diet, insulating our homes— good as all those actions and choices are. For people in the poorer, developing world, it is about the right to choose and having the means to choose how many children a woman has or doesn’t have. A choice denied to over 270 million women worldwide currently.

In the UK, more people are making that positive, personal choice and action to have a smaller family. But a recent survey also revealed a more worrying trend, finding that some young people are deciding not to have children because of their fears for the future.

This shift to thinking about smaller families is happening faster than we thought, is both positive and worrying. Young people are reacting, thinking in terms of environmental responsibility and global justice. But also out of pessimism for the future, not just for themselves, but for the generations to come. I’d much rather the choice to have a smaller family or not have children was driven by the instinct to be in harmony and balance with our planet, our habitat, and our home—through optimism in our human nature and instinct.

THE 18TH GOAL

It took humanity 200,000 years to reach one billion people and only 200 years to reach seven billion. The challenges that humanity faces today stem mainly from overconsumption and overpopulation. Yet policymakers often fail to consider the two factors together, and largely neglect population growth in particular. The overall human impact on the global environment is the product of population size and average per capita consumption.

The United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has concluded that population growth and economic (consumption) growth are the two main causes of global warming. Today, a child born in the US will produce 24 times more consumption carbon emissions per year than one born in Nigeria. Every one billion extra people on the planet comes with an extra ten billion farmed animals, reared and slaughtered every year.

Between 1960 and 2000, the world’s population doubled from three billion to six billion. This growth contributed to greater pollution of land, lakes, rivers, and oceans, as well as urban overcrowding and a higher demand for agricultural land and freshwater—in turn encroaching on natural ecosystems.

We hit 8 billion people on Earth in mid- November 2022, according to the United Nations latest data. It forecasts that this figure will rise to around 11 billion by 2100. A population increase on this scale would create more pollution, require a doubling of global food production under difficult conditions—including climate disruption—and result in more people suffering during conflicts and famines.

Yet the huge projected increase in the world’s population this century is avoidable. The size of the population in 2100 can be influenced now by international debate, government programs, and individual choices. More specifically, an additional SDG—an 18th goal—to “dampen population growth” would promote funding for voluntary, rights-based family planning.

AGAINST ALL ODDS

So I hold to an optimistic narrative and outcome for the human story—not a fairy tale I tell my children in denial of what the science warns is already embedded in the system, but a realistic, gritty tale reliant on individuals and communities to make the right choices and find sustainable solutions against the odds.

The Musks and their cult followers can blast off to Mars. We have everything we need here on Earth. That’s our mission.