Attenborough film: Saving our planet requires ending population growth

David Attenborough’s ‘A Life On Our Planet‘ highlights the rampant destruction of nature caused by human population growth and unsustainable consumption, as well as the positive and urgently needed actions we must take to save our one and only planet. Population Matters Director Robin Maynard reviews the film.

Hopefully millions of people across the world will watch A Life On Our Planet, make the individual positive lifestyle changes, and demand the real action from their political leaders, as signposted in the WWF-UK and Netflix co-produced film.

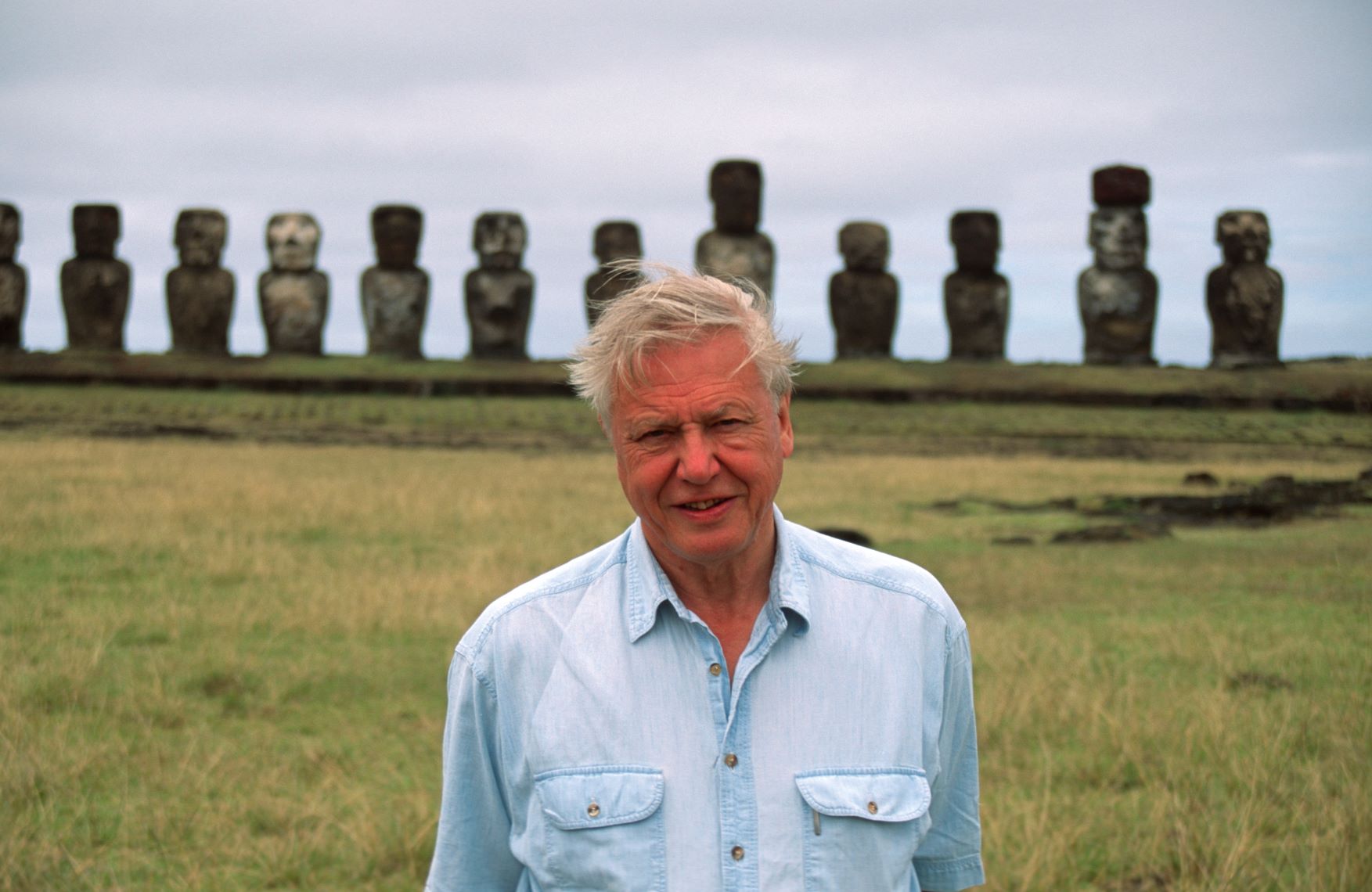

The ‘life’ focused on is that of legendary broadcaster and PM patron, Sir David Attenborough, who over the past 60 years has brought the wonders of the natural world into our living rooms whilst over the same period, with growing disquiet, witnessing the most rapid, comprehensive destruction of wild species and places since the last mass extinction event that ended the dinosaurs.

Of course, the film is about all our lives – and whether, depending upon our use of the unique human trait of foresight, we can adapt our ways of living to ensure a fairer share of the world’s available resources for all, whilst protecting and restoring the wild. And crucially, do so in time and at scale so that this precious ‘blue marble’ (the only planet evidently able to support complex life) remains habitable.

Attenborough has been criticised for not acknowledging the accelerating destruction of the natural world in previous documentaries. The camera never went fully wide-shot to show the encroachment of urban areas, the conversion of plains and forests to agriculture, the scale of oil, coal, tar sand and mineral extraction (visible from space) which fuel the planet-wrecking lifestyles of those of us living in high-consuming, ‘developed’ countries. Whatever his part in those earlier editorial decisions, he doesn’t shrink from showing the impacts and consequences in this “witness statement” and deeply personal reflection on the laying waste of the wonders he’s been “privileged” to see first-hand.

Unlike most broadcasters and conservation organisations, Attenborough has not shied away from the plain truth in his other roles off-air. Not least as a patron of Population Matters:

“As I see it, humanity needs to reduce its impact on the Earth urgently and there are three ways to achieve this: we can stop consuming so many resources, we can change our technology and we can reduce the growth of our population.”

A Life On Our Planet proposes four key actions: ending population growth, switching to renewable energy, reducing meat consumption and sustainable management of oceans. On population, Sir David points out the win-win, empowering solutions we campaign for at Population Matters: investing in education and women’s rights and raising people out of poverty. He rightly states,

“Why wouldn’t we want to do these things? Giving people a greater opportunity of life is what we want to do anyway. The trick is to raise the standard of living around the world, without increasing our impact on that world.”

The most powerful sequence is when the camera holds its focus for an uncomfortably long period on his face and visible anguish at this emptying of Eden – even more eloquent than his words. The film could have ended there. The preceding sequences made it plain what we all need to do, stop doing, allow others (poorer countries and other species) to do more of, and to choose ‘leaders’ capable of acting on the evidence. But the producers can’t help but sugar the pill they’ve served up. Suddenly the mood music lifts as a not very convincing sequence of techno-solutions are put forward: The American Plains restored to grassland, with vast herds of bison roaming amidst wind-turbines; drones sustainably harvesting reforested rainforest; oceans, which we’ve just been told are 90% over-exploited, replete with huge shoals of fish and spouting pods of whales amidst photo-shopped images of futuristic ‘responsibly–sourcing’ fishing craft.

An excellent review from the unexpected quarter of the New Musical Express catches that disjoint: “You can almost hear the crack in his voice when he says the solution is “simple”. Whether he genuinely believes that we all have the capacity for change or he just doesn’t want to end the film on a downer, it’s still a bitter pill to swallow in a year like this. If people kick up a fuss because they have to wear a mask in Asda to protect their own gran, what chance does a rare finless porpoise or a poison dart frog have when the cost of protecting them demands so much sacrifice? The lives of animals and plants might be more closely tied to our own than we like to admit, but a remarkable film like this needs to move us to action instead of tears if we have any hope of saving them.”

Another shortcoming is that the film claims that our population will stabilise by the end of the century – unfortunately, according to the UN’s latest data, there is only a 27% chance of this happening. Whether we achieve a sustainable population sooner rather than later depends entirely on how quickly world leaders, civil society and investors recognise the urgency of our situation and embrace much-needed, positive solutions.