China’s changing child policy: what does it mean?

China’s panic over the consequences of a falling birth rate is typical of concerns across Asia and increasingly, the world’s wealthiest countries. The Chinese government’s response – moving its family size limit from one to two to three children – is a typical mix of apparent liberalisation and continued state control. Our Head of Campaigns, Alistair Currie, looks at the policy and the drivers behind it, and asks what it can it tell us about shifting demographics and how governments respond.

China’s situation

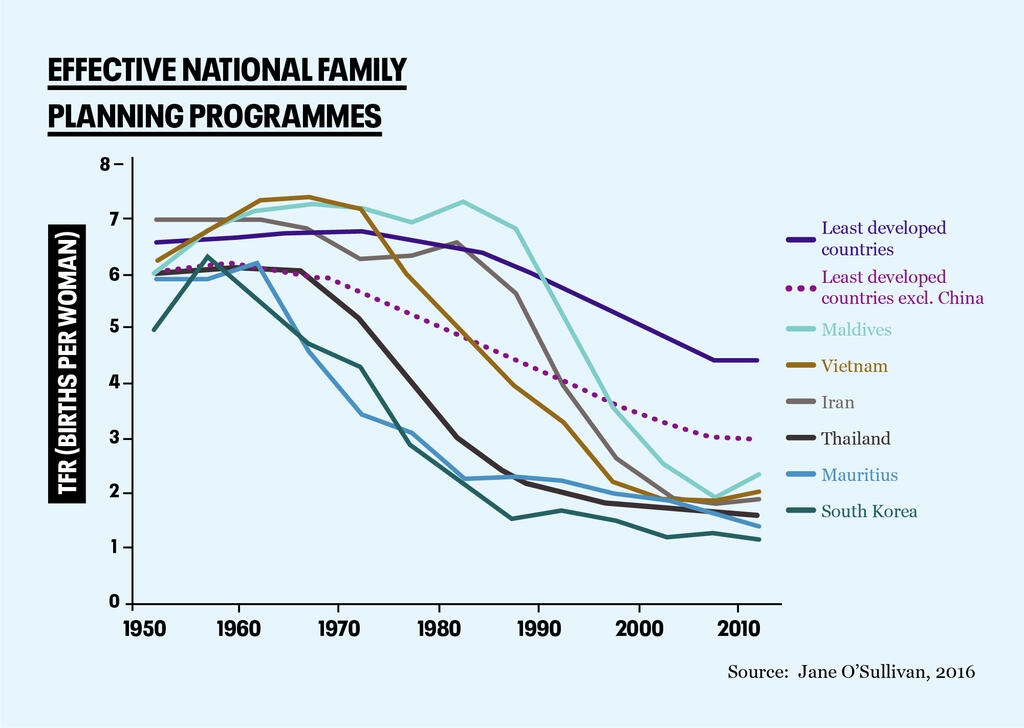

China has two claims to fame in the population field – the world’s largest population and the world’s most notorious population policy. Soon, however, India will eclipse it in total population size, and while the one-child policy is undoubtedly the most famous example of a population policy, it sadly obscures the far greater number of effective, ethical and empowering policies pursued in many other countries with genuine success. Its consequences of human misery, forced abortions, and infanticide are clear evidence that attempting to control human population without respecting human rights is wrong. Sadly, too, China’s government continues to abuse human and reproductive rights where it perceives it is in its interest to do so, with deeply disturbing evidence of a eugenicist policy directed against its Uyghur Muslim community.

“Maintaining the country’s advantages”

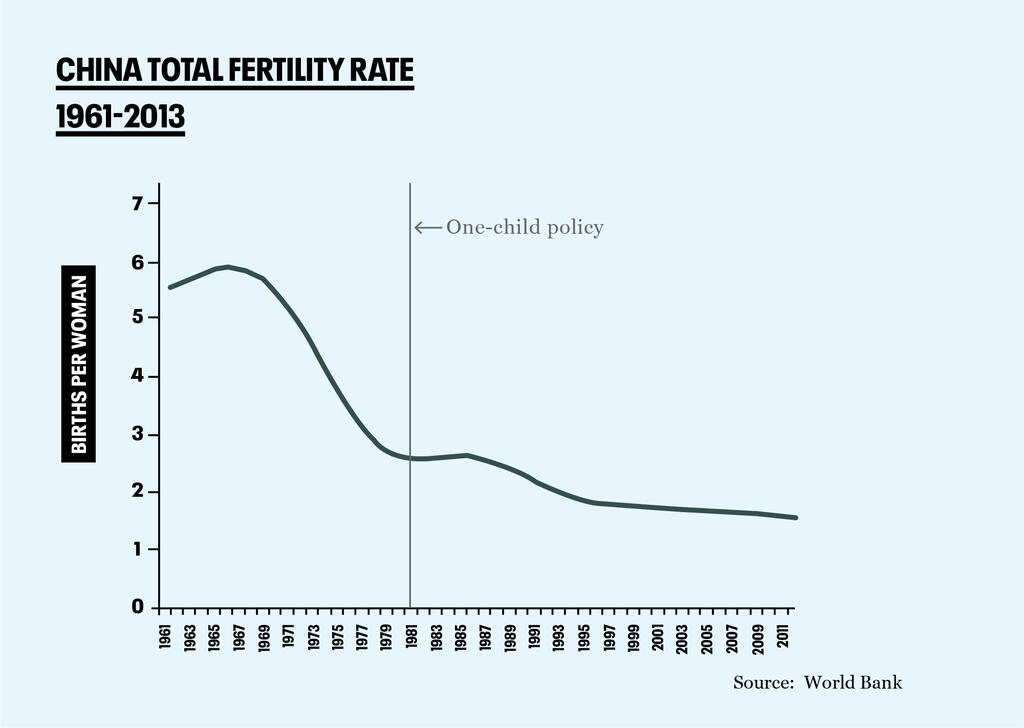

A new consequence has been added in recent years to the charge sheet against the one-child policy – an ageing population which China’s economy will be unable to support. Seemingly unable to let go of the principle of controlling family size, the Chinese government’s reponse was to “relax” the policy to a two-child limit in 2016. That change has had no significant effect in reversing the trend, with the latest Chinese census showing a third fewer babies (12 million) being born in 2020, compared to 2016 (18 million).

Just last week, the Chinese government announced a new limit of three. As Chinese people have pointed out, however, if the change to two didn’t work, why should a change to three be expected to work any better?

Tellingly, the government has justified the changes as “maintaining national security and social stability” and keeping “our country’s advantages in human resource endowments”. Ominously, the announcement also talked of “strengthening the education and guidance” of young married couples, as well as “controlling bad social customs.”

China’s government does not hesitate to limit the freedoms of its citizens where it perceives it to be in the national interest to do so, and if the latest changes do not prove successful, there is a real risk of sexual and reproductive health and rights being limited, as is already happening to serve a population growth agenda in some other countries.

The “silver tsunami”

China is far from alone in seeing the age profile of its population changing. There are around 727 million aged 65 or older alive today. While their share is now about 9% of the total population, it will increase to some 16% in the next 30 years, meaning one in six people will be aged 65 years or older by 2050.

This change is accompanied by a growing narrative that declining populations and a higher number of old people represents an economic and existential crisis for nations. With 55 nations (including China) expected to see their populations reducing by 2050, policies to boost birth rates are increasingly common from Iran to Korea and Hungary to Japan. The perception of the problem, and the proposed solution, are both deeply problematic.

The good news

The “demographic disaster” of higher numbers of older people has now become economic orthodoxy, and looms increasingly large in the public consciousness. The reasons for it must be celebrated, however. Lower fertility and birth rates are overall a sign of huge social progress: people moving out of poverty, women being empowered, good health care, and modern family planning allowing people to determine how many children they have. It is also a consequence of better lifelong health, lower childhood mortailty and advanced modern healthcare that people are living longer.

Nor are old people the burden that they are often portrayed as. People over the age of 65 contribute around £160 billion to the economy of the UK through employment, volunteering and “services” such as child care of their grandchildren, allowing the generation between to work.

Similarly, even where old people are dependents, they are not the only ones. Children are also dependent, and themselves require infrastructure and investment, for both societies and families. Fewer school or university places needed can mean higher quality education and training for the same outlay (or less), generating more productive adults at lower cost. Similarly, families with fewer children are able to invest more in their wellbeing and development, including financially in the form of support in buying property or inheritances.

A larger work force is far from necessarily a good thing. Many countries with high population growth and large numbers of children and young people suffer from unemployment and economic stagnation. As automation makes some jobs redundant, a smaller workforce can be advantageous to a nation.

A smaller workforce also tips the balance of power towards employees, increasing wages and providing opportunities for traditionally disadvantaged groups for better employment.

Managing change

Of course, demographic changes such as these must be managed. But there are multiple policy options are open to governments. Among the most signifcant are:

- Better personal pensions. People contributing more for their own retirements not only means less state expenditure on pensions, but increases funds for pension providers to invest in the economy.

- Greater investment in serving the needs of the oldest people. Increasing longevity does lead to greater demand on health and care services. Public expenditure should follow the need. Choosing to spend more on caring for our older people and raising tax revenue in order to do so is a legitimate and appropriate policy option.

- Increasing retirement age. Most people are healthier and more able to work at age 65 or 70 than they were when that retirement age was set decades ago, and many are willing to. This both saves pension expenditure, and increases productivity. Experienced, older employees in many settings will be of more value to employers than younger ones.

- Prepare for demographic change in the world of employment. Employment opportunities which are being lost in other areas as a result of, for instance, automation can be redirected to the health and care sector. Training and recruitment provision should reflect that growing need.

- Judicious and well-managed immigration. More people living in wealthier countries increases consumption and climate emissions – and more young people eventually means more older people when their retirement comes around. However, if well-managed, the transfer of skills and labour from one country to another can provide opportunities to meet employment or skills gaps and boost tax revenues. In the right circumstances, it can form part of the mix of policies managing the short term impacts of demographic change.

Reframing the economy

Much of the concern about ageing populations comes from the perspective of a traditional growth economy, in which increasing consumption, expenditure and economic activity is seen to define progress. An expanding number of producers and consumers is central to that process. However, not only is this “great acceleration” the principal driver of our environmental crisis, it is also failing to serve people. A growing number of economists are recognising the need for economies to be based on providing wellbeing, and that a greater quality of life is not determined by a greater amount of money changing hands. Greater respect and care for older people surely is one measure of that better quality of life.

Similarly central to a good quality of life is a healthy environment, providing for everyone’s needs. Increasing population growth is a critical driver of the destruction of the environment, which must now and for the foreseeable future be the overriding focus of all policies. We can manage the challenges of an ageing society through good planning and prioritisation: environmental collapse will leave us with no options to choose from.

“The economy is a wholly owned subsidiary of the environment.”

– Herman Daly, former World Bank Economist and Expert Advisor to Population Matters

Global population is still growing at a rate of 80 million people per year – a trajectory which exacerbates our environmental crisis, traps people in poverty and postpones achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals. China’s change in policy is to be very guardedly welcomed as a step in the right direction from a human rights perspective, but it must abandon the principle of state control of family size altogether. Replacing that with an actively pro-natal policy, however, is wholly the wrong approach. China is, for instance, the world’s largest single producer of greenhouse gas emissions. The end of population growth in China is to be welcomed.