China’s Reproductive Rights: Calls for a Childbirth Culture

Our ongoing series returns to our Welcome to Gilead campaign, examining restrictions on China’s reproductive rights and global trends in reproductive freedom. This update explores recent pronatalist measures in China and their impact on women’s autonomy, following our 2021 Gilead report.

No More Dragon Babies

China’s reproductive rights are facing increasing government intervention. Last year, China saw a rise in births for the first time since 2017, reaching 9.54 million, up from 9.02 million the previous year. Many experts put this down to it being the Year of the Dragon in the Chinese Zodiac calendar, where it’s believed that children born in that year will be destined for great success and fortune.

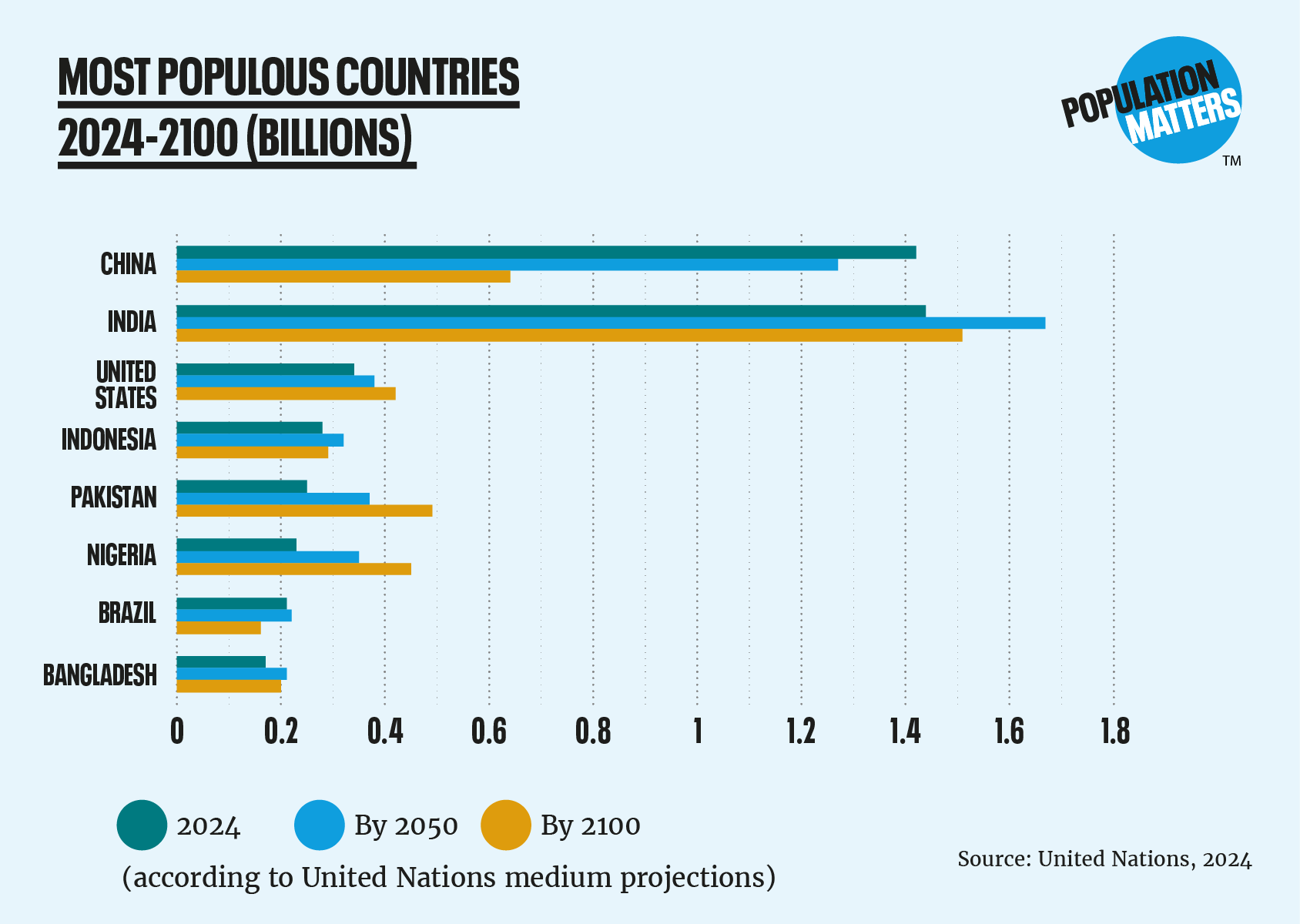

However, despite a slight uptick in births last year, China’s population has continued to decline. Its population has dropped to 1.409 billion – a 2.08 million decrease from 2022.

China’s population decline is due to a low birth rate, below the replacement rate of 2.1 which is required for a population to maintain a constant size.

This is part of a broader demographic transition that mirrors other high-income countries. As China has rapidly deindustrialised, its workforce has moved into the service sector. The population has become more educated and skilled, with more women in the workforce, meaning people start families later and have fewer children.

However, this population decline has sparked concern among government officials who fear a future economic downturn and have begun to pressure younger generations, women particularly, into having more children.

Top Down Pronatalist Pressure

In a speech in 2023 to the All-China Women’s Federation, President Xi Jinping called for the organisation to “actively cultivate a new marriage and childbirth culture, strengthen guidance of young people’s views on marriage, parenthood and family, as well as promote policies to support childbirth”.

The Chinese government has since introduced a range of policies to tackle the low birth rate including tax benefits, cheaper housing, and cash incentives to encourage people to have more children.

In 2021, central Chinese Communist Party authorities set out a comprehensive nationwide pro-natalist policy framework. Local authorities have since followed suit with the launch of pilot projects aimed at building a “marriage and childbearing culture for a new era” in dozens of Chinese cities led by the China Family Planning Association.

At a local level

Jingzhou, in Hubei province, is one of the latest cities to offer cash subsidies to families with multiple children, providing 6,000 yuan for a second child and 12,000 yuan for a third.

This has also led to more invasive practices such as reports on social media of local officials knocking on doors and cold-calling women to inquire about their menstrual cycles and ask when newlywed couples plan to have children.

The Beijing government has also called on local officials to put in place early-warning systems to monitor changes in population at the village and town levels around the country. Not since the peak enforcement of the one-child policy has the central Chinese government paid such close attention to the reproductive lives of its citizens.

However, despite these policy incentives and pressures, China’s birth rate has remained consistently low.

The YuWa Population Research Institute report that China is one of the most expensive places to raise a child and that economic concerns have put people off wanting to have more children.

Others point to the legacy of state violence of China’s one child policy and how this has led to a generation of women sceptical of Beijing’s new pro-birth agenda.

Rollback on Abortion Access

Whilst positive incentives have so far done little to reverse the trend of China’s consistently low birth rate, other more coercive measures have been introduced including further restrictions on women’s reproductive rights and access to abortions:

- In 2018, Jiangxi province in eastern China introduced a policy that anyone seeking to terminate a pregnancy after 14 weeks of gestation must prove that the procedure is medically necessary and obtain signatures from three doctors.

- In August 2022, the National Health Commission’s (NHC) new birth-encouraging plan included a directive to “reduce abortions that are not medically necessary.”

- In November 2022, China’s National Medical Products Administration banned online sales of two abortion pills.

- In February 2023, a court in Chengdu city ruled that termination of pregnancy without spousal consent or “legitimate reasons” constitutes a violation of men’s right to reproduction. The case eroded existing precedents and restricted the grounds on which many women could access abortion, and in effect denied the autonomy of married women to make decisions about their own medical procedures.

Silver Lining

Whilst there has been a trend towards restricting access to abortion in China in recent years, this also comes at a time of fierce resistance as more Chinese women are educated and in work than ever before, bringing about a rise in feminist discourse in the country.

However, with the extraordinary rise in feminist consciousness over the past 20 years, any attempts at introducing explicit abortion bans in China will likely see enormous public pushback. Simply citing economic need and evoking nationalism are unlikely to resonate with the country’s increasingly independent and politically conscious women.”

Irene Zhang: Junior Research Scholar, APF Canada

As witnessed recently in America, it’s important to stay alert to policies that adopt a pronatalist agenda especially when they start to gradually erode women’s rights as this can lead to an irreversible ‘tipping point’ as seen with the overturn of Roe v Wade. Population Matters will continue to monitor activities in China on our Gilead Watch page.