Population: the numbers

Population is a dynamic field. There have been significant changes in birth rates and the population trajectories of countries and continents in recent years. Global population is still growing by more than 80 million a year, however, and is most likely to continue growing for most of this century unless we take action.

current world population

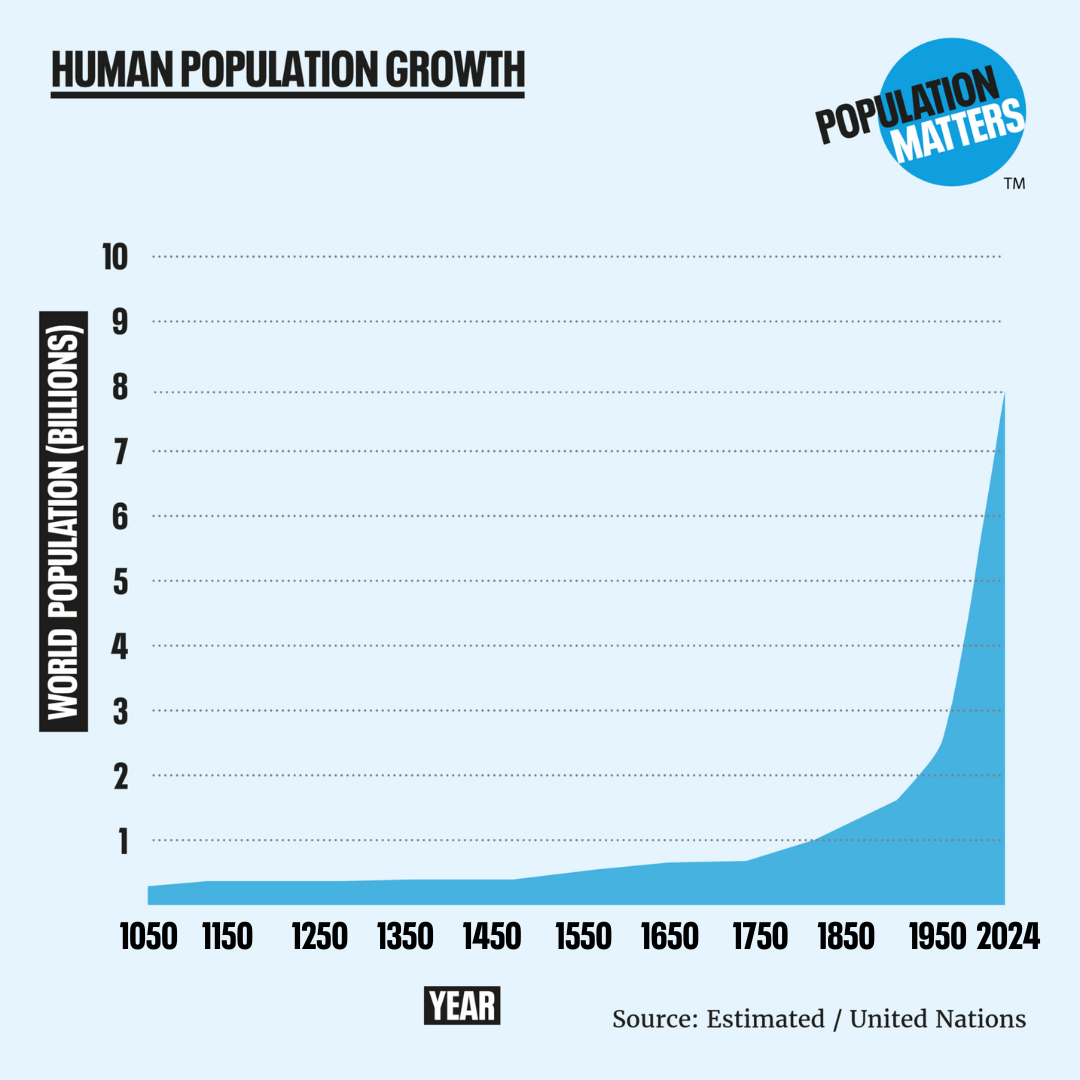

How we got here

Until the time of Napoleon, there were less than 1 billion people on Earth at any one time. Since the Second World War, we have been adding a billion people to the global population every 12-15 years. Our population is more than double today what it was in 1970.

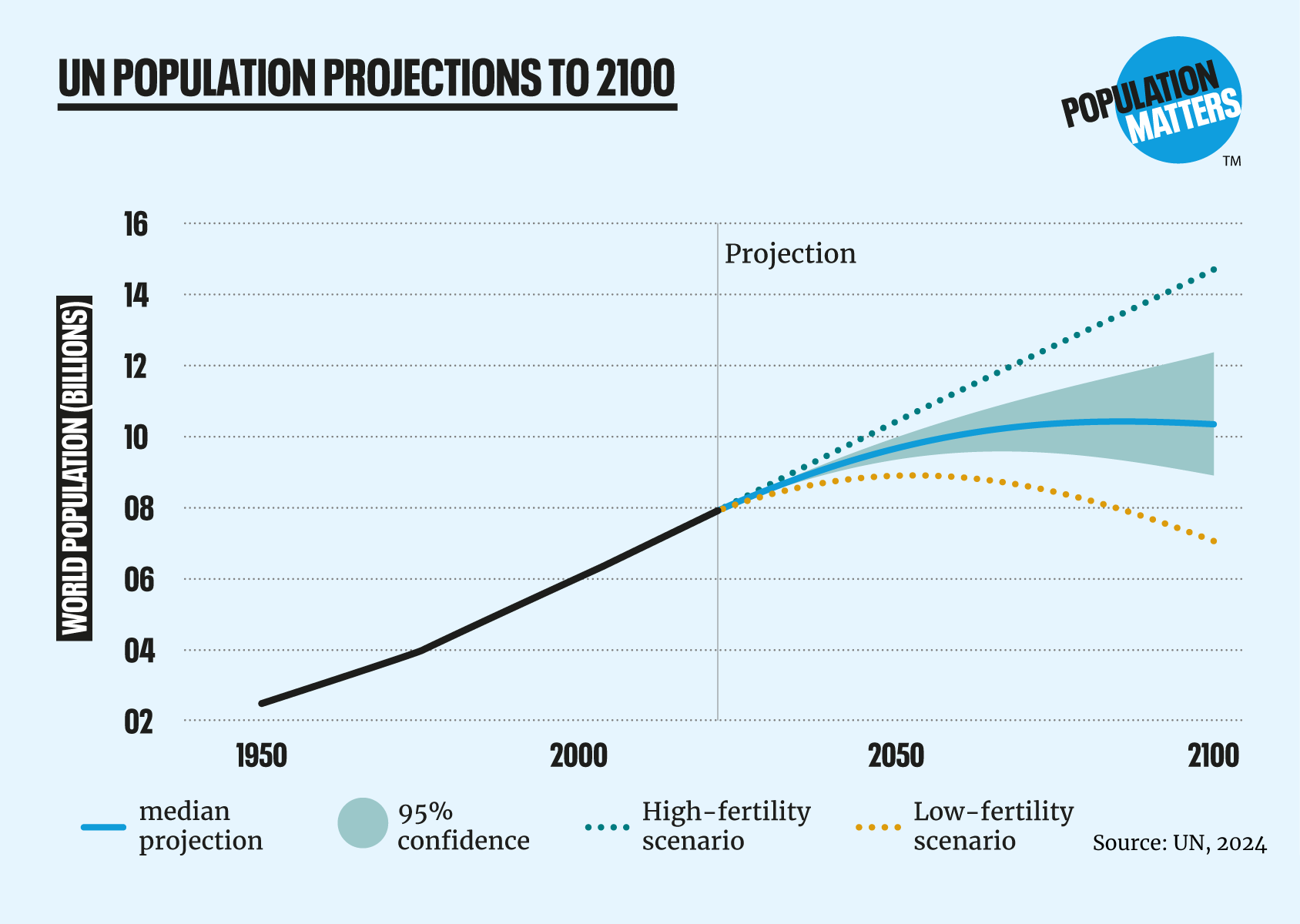

Where we could be going next

Every two years, the United Nations makes projections for future population growth. Its latest medium projection – the most likely scenario – is a population 10.3bn in the 2080s, two billion more than today. Because many factors affect population growth, it makes a range of projections depending on different assumptions. Within its 95% certainty range, the difference in population in 2100 from the highest to lowest projection is 3.5 billion people – almost half the population we have today.

The dotted lines on the graph above shows the UN’s projected population if, on average, every other family had one fewer child or one more child than in the median projection (‘low fertility and “high fertility” scenarios).

Explore population growth and its effects on our planet

Our Population Explorer is an interactive online tool providing insights onto population growth and its impacts on nature, climate change and our demand for the Earth’s resources. You can investigate different areas, explore solutions and interact with the graphics to find out more. Check it out!

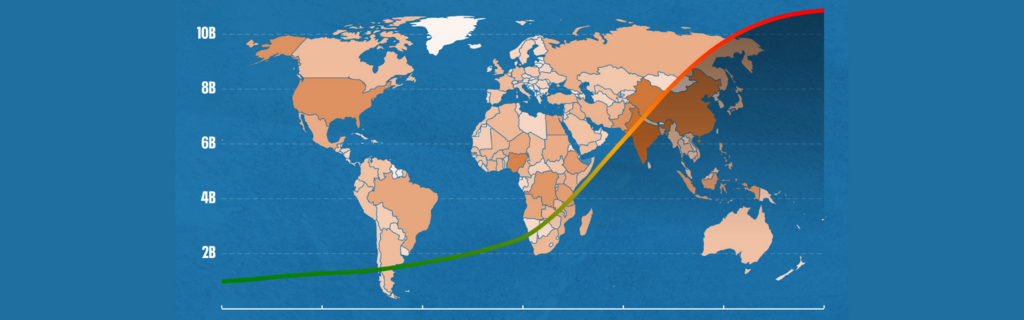

Where population growth will occur

- Eight countries will make up over half the projected total population increase by 2050: India, Nigeria, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Pakistan, Ethiopia, Tanzania, Egypt, and Indonesia.

- As expected, India overtook China as the world’s most populous country in 2023, and China’s population has started to decline.

- In 63 countries and areas, containing 28 per cent of the world’s population in 2024, the size of their population peaked before 2024.

- In 48 countries and areas, representing 10 per cent of the world’s population in 2024, population size is projected to peak between 2025 and 2054.

(Source: United Nations Population Fund, 2024)

The impacts of rapid population growth and its causes continue to pose a major impediment to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals, in particular eradicating hunger and poverty, achieving gender equality, and improving health and education. Poverty is also a significant driver and predictor of population growth. Total population in the UN’s designated Least Developed Countries is projected to rise from just over 1bn in 2020 to 1.76bn in 2050.

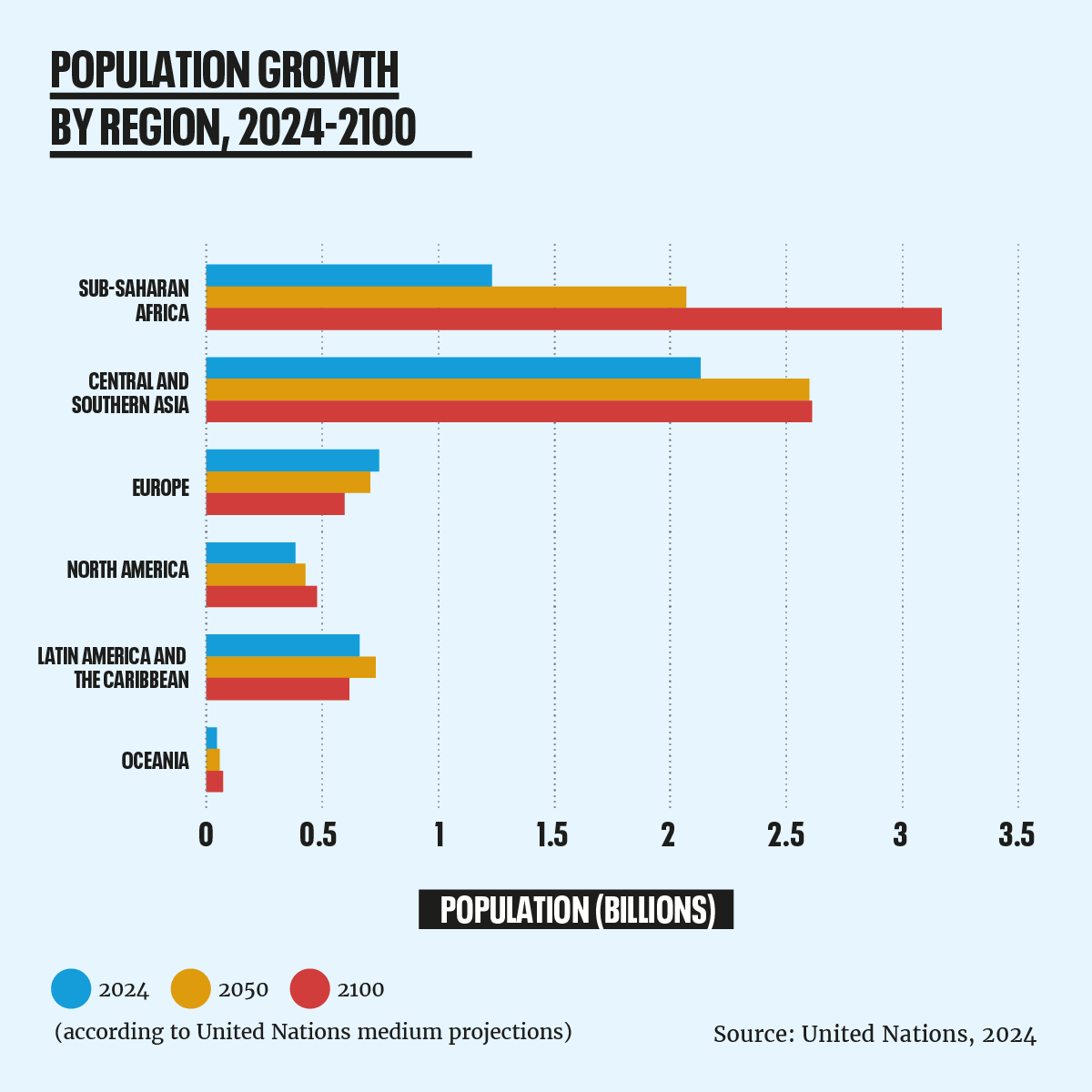

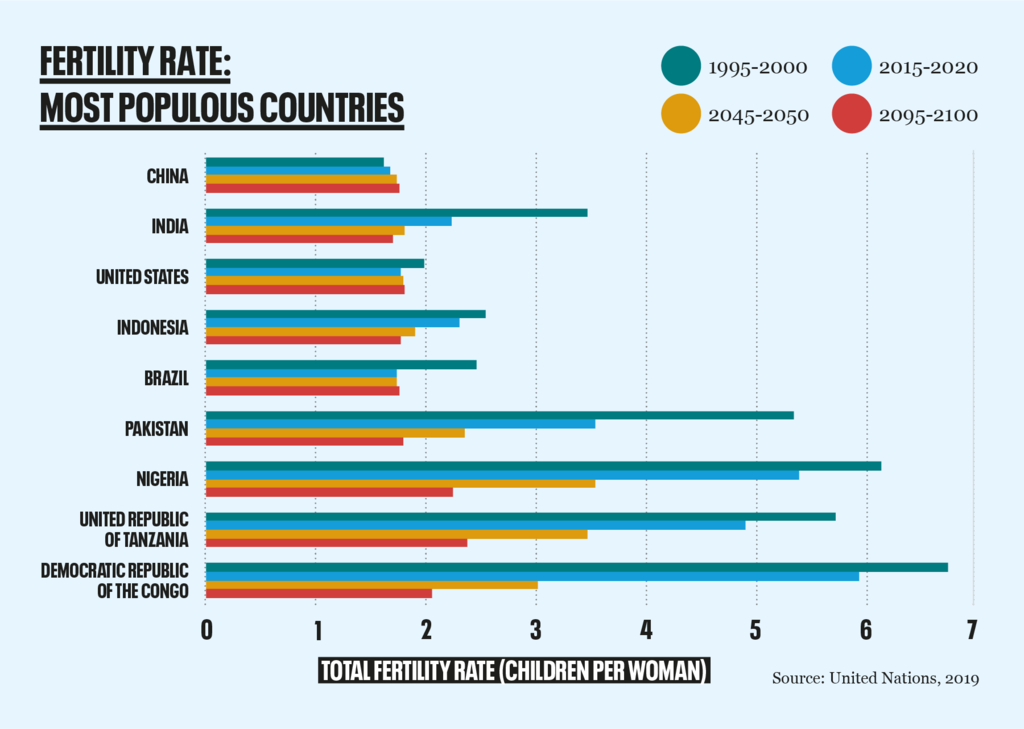

More than half of the people added to the world’s population over the rest of the century will be in sub-Saharan Africa. Although it is falling, fertility rate (the average number of children per woman) remains high in most African countries (see ‘Bringing Down Fertility’ below for why). Due to its high fertility rate, sub-Saharan Africa has a very young population: 60% of the population is less than 25 years old. That means that many people are entering their childbearing years. Thanks to improvements in access to health care, life expectancy is increasing and child mortality is declining, meaning there are now more generations alive at the same time.

These figures regarding populations of different continents and countries include assumptions about future migration, but are necessarily very speculative. Climate change, poverty and population pressures themselves will lead to a highly mobile global population, with Africa likely to be the largest source of emigrants.

Unequal impact

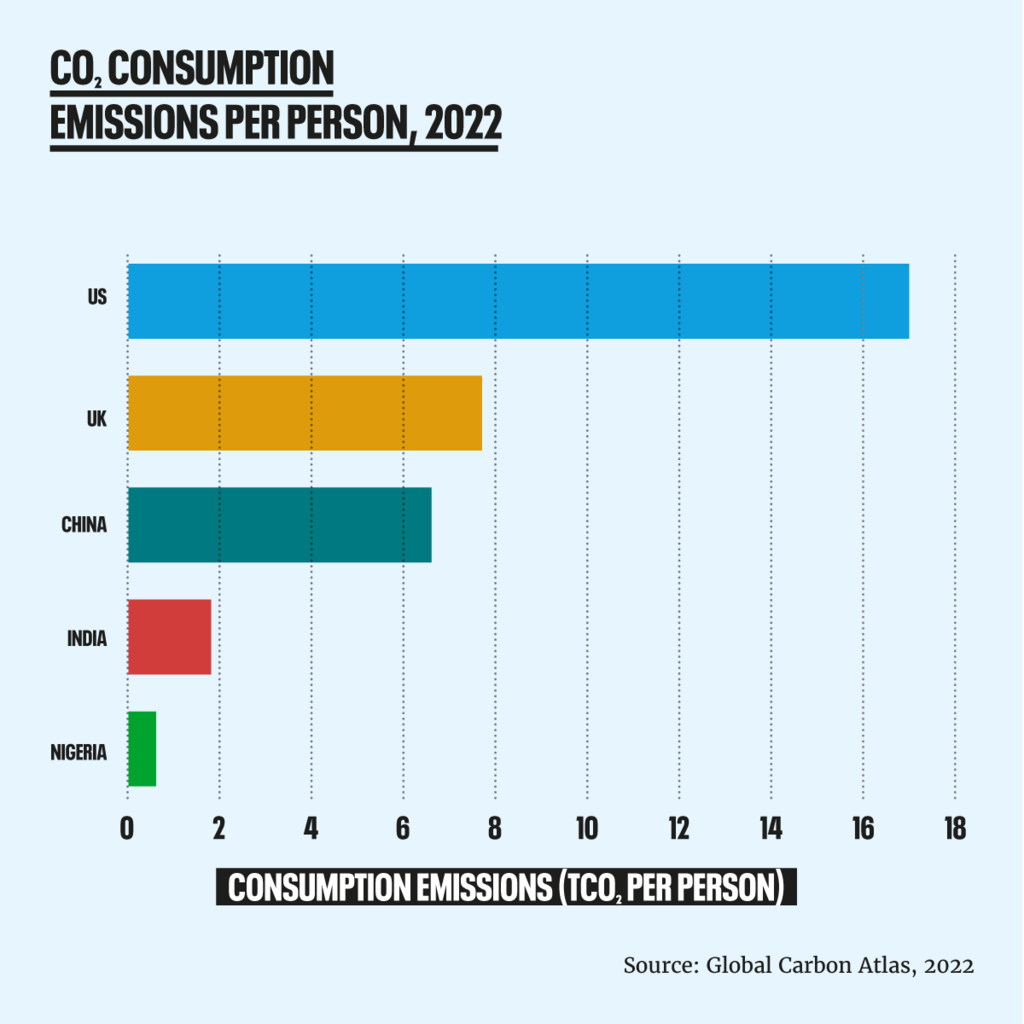

It is important to remember when looking at all these figures that while population growth is highest in the Global South, and relatively low in most parts of the Global North, consumption, resource use and carbon emissions are far greater in the richest parts of the world. That means that the global environmental impact of each individual in wealthy countries is far higher than in poor countries. To truly achieve a more sustainable world for people and the planet, we must also work to address overconsumption.

Fertility rates and population

‘Total fertility rate’ is the number of births per woman over the course of her life, monitoring changes in ‘total fertility rate’ over time gives an indication of social and economic progress. A TFR of 2.1 is the “replacement rate” – a population with that TFR will eventually stabilise.

- The latest UN estimates for global TFR is just under 2.5 (although more recent estimates place it at 2.3).

- TFR is highest in sub-Saharan Africa, at 4.6.

- Almost half of all people now live in a country or area where TFR is below the replacement rate.

- Fertility rates are expected to fall worldwide, to the point where no country is expected to have fertility of more than five births per woman by 2050.

Populations are also affected by death rates, net migration and the proportion of people of childbearing age. Populations of countries with fertility rates below replacement level often continue to experience natural increases (births minus deaths) for some time. In particular, where birth rates have recently been high, when the babies born in that period reach childbearing age they increase the number of families, even though the size of their families is smaller than in the previous generation. This is called ‘demographic momentum’ and means that the impact of changes in fertility normally takes many decades to be reflected in population.

The effect of migration

Many countries with less than replacement rate are also growing due to net migration. When immigration is greater than emigration, this increases numbers of people directly but it can also increase the birth rate. This is usually because migrants tend to be younger people of working age, so are more likely to have children than the average for the existing population, and because in some cases, they come from countries or cultures with traditionally higher fertility rates and family sizes.

In other countries, net migration is outward, meaning their populations are decreasing, or growing at a smaller rate than they otherwise would. When the people leaving are of reproductive age (which is usually the case), emigration causes the fertility rate to fall even further. In some cases, these countries also have low fertility rates already (such as Bulgaria and Romania).

(You can find out more about the meanings of the technical terms used on this page in our Glossary.)

Empower women

Fertility rates decrease rapidly when women are empowered, when children (especially girls) stay in education for longer, when countries become more affluent, and, crucially, when people can use modern contraception.

More than 200 million women in developing countries currently have an unmet need for family planning, meaning they do not want to get pregnant but are not using moden contraceptive methods. Research published by the Guttmacher Institute shows that this is often because they are unable to access family planning but more commonly because of concerns about side effects and misinformation, and, in nearly a quarter of cases, because their male partners or others close to them oppose contraceptive use. Contraception provision must be accompanied by education, support and female emancipation to be effective.

Another important factor in uptake of contraception is desired family size. Religious, cultural and social influences all play a part in that, as do economic and political factors. Where people cannot rely on the state to support them, they tend to have larger families to ensure they have children who can support them. Where child mortality is still high, people also tend to have more children. The “value” of women and girls may also be judged by the number of children they have (not just in places where women are not empowered) and traditions valuing larger families are often internalised.

Effective family planning programmes, such as that in Thailand, have helped individuals exercise their reproductive rights to realise their desired family size.

Test your knowledge on population

How much do you know about our population, how it’s changing, its impacts and solutions? Take our quiz to find out.