A hidden agenda? What population campaigners really want

In January 2018, The Sunday Times published a column by journalist and commentator Dominic Lawson, in which he damned concern for population as a witches’ brew of eugenics, colonialism, coercion, hypocrisy, scientific fallacy and blaming the poor. His criticisms echo those which population concern campaigners face almost every day.

We understand the reasons such accusations and concerns recur. It’s a difficult issue and, in some respects, has a chequered past. It’s deeply disappointing, however, to see such a misrepresentation of a cause that is positive, rational, relevant and driven by a deep concern for people everywhere, and the planet we share with other species. Population Matters, and some of our patrons, were named in the article and dismayed as we were to see that litany yet again, it is also a reminder that the case against population concern is often reliant on assumptions and misinterpretations – and occasionally, sadly, simple hostility.

This urgent and vital issue deserves an open, honest and unprejudiced examination. We welcome the opportunity to confront the criticisms we face most often head-on.

Getting it wrong

A charge frequently levelled against population concern advocates is that past predictions of crisis and disaster were not fulfilled. The two classic examples are those of Thomas Malthus, who theorised in the late 18th century that population would inevitably outstrip food supply leading to starvation, and Paul Ehrlich (a patron of Population Matters), whose The Population Bomb in 1968 predicted mass starvation and famine within a generation. Their predictions turned out to be wrong – or at least hugely premature. In both cases, improvements in food production technology and techniques allowed food supply to keep pace with population growth.

It is, however, wishful thinking at best to extrapolate from Malthus and Ehrlich’s unfulfilled predictions that food production can meet the demands of any population size. At the time Malthus made his predictions, less than a billion people lived on the planet – when Ehrlich made his, the population was less than half what it is today. In 1970, Norman Borlaug, known as the” father of the Green Revolution” which vastly increased crop productivity in the 20th century, himself said that it had only given humanity a “breathing space” – not a solution to hunger.

Today’s 7.6bn and the 2bn more expected by 2050 must feed themselves from soils with, according to the UN, less than 60 more harvests to give, decimated fish stocks, a finite supply of fresh water facing even greater demands upon it and, most frighteningly, the risk of a collapse of insect pollinators and of millions of square miles of land made unproductive by climate change. Those challenges demand urgent attention, not a complacent dismissal based on the mistakes of the past.

More than food

Concerns about population are no longer confined to how we feed ourselves. Malthus and even Ehrlich lived in worlds in which the scale of the global environmental crisis we face today was almost unimaginable. Just a few weeks ago, 15,000 scientists signed a “warning to humanity” detailing the gravity and urgency of the environmental threats of our time. Unlike Dominic Lawson (who fails to acknowledge environmental problems at all), those best qualified to know and evaluate the facts are unashamed to identify population growth as a “primary driver” of impending environmental catastrophe and to be clear about a solution:

“It is time to re-examine and change our individual behaviors, including limiting our own reproduction (ideally to replacement level at most)”.

Focusing on the historical errors by population advocates on food supply is a convenient and sloppy way of avoiding the critical questions of today: can our atmosphere, soils, water supply, seas, forests, grasslands and fellow species withstand the pressures applied by billions more of us than existed just a generation ago – and the billions more to come?

Coercion

In his article, Dominic Lawson identifies one notorious example of the dark history of population control – forcible sterilisation in India in the 1970s – another being China’s one child policy. These great and shameful injustices deserve our condemnation. Like the vast majority of people concerned about our unsustainable population, Population Matters, for the record, is wholly opposed to punitive population control, forced sterilisation or abortions, or any other activity which violates human rights. The right to have children, or to have none, is a human right.

Coercive policies have cast a long shadow over population concern but dwelling on them and ignoring the explicit condemnations of those policies made by population concern advocates is deeply unfair. Most of these abuses were perpetrated by regimes or governments that were contemptuous of human rights in many ways, and/or may have reflected dynamics such as endemic or institutionalised racism in the societies in which they occurred.

Population Matters exists in and entirely endorses a sphere of action that recognises and protects human rights. It is obvious that one can believe that people should do something without believing they should be coerced into doing it. Population concern advocates no more hold that people should be forced to have fewer children than democratic politicians believe people should be forced to vote for their parties.

Solving the problem

Coercion is not needed to bring down fertility rates. Countries like Bangladesh and Thailand have achieved remarkable results without coercion. We can reduce, and eventually reverse, population growth through actions which help people in multiple other ways – female empowerment and education, lifting people out of poverty and providing access to and education about family planning. Combined with incentivising and promoting the positive case for smaller families, population can, and should, be brought to sustainable levels through the free choices people make.

Double standards and punching down

Lawson saves his trump card until last (although for many, it is the first accusation to be made): population concern is about rich (usually white) people telling poor (usually not white) people to have fewer children while they have as many as they want. A parallel accusation is that high-consuming people from the developed world are responsible for the environmental problems we face but seek to blame poor people for having large families. Some critics refer to it as “punching down” – attacking those more vulnerable than yourself.

In his article, Lawson skewers what he calls “population control advocates” with the killer accusation that rich people demanding that the poor change their ways is hypocritical and may even be “eugenics dressed up as environmentalism”. A killer blow – if only it was true.

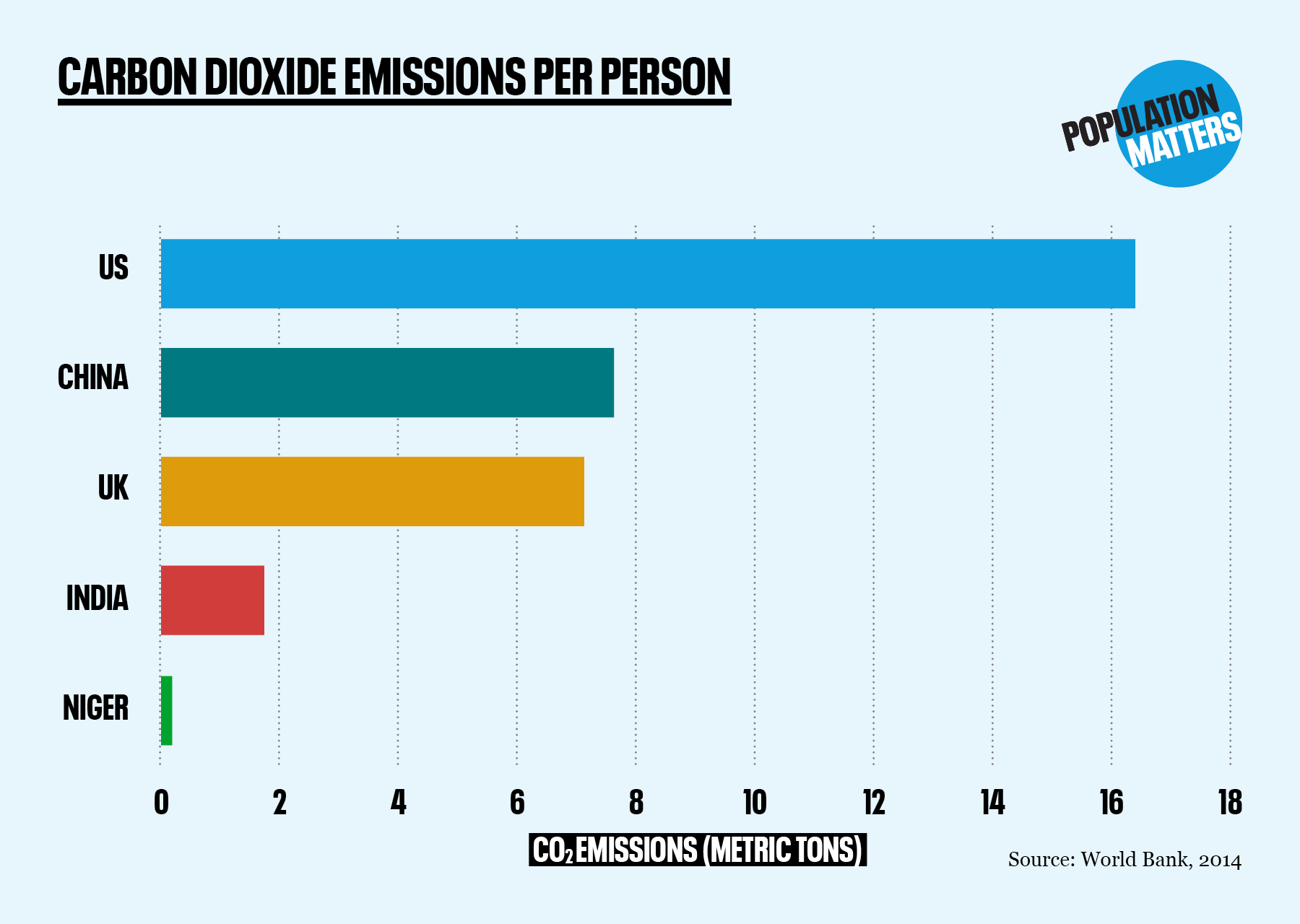

Population Matters – along with the vast majority of people concerned with population – is absolutely clear that the world needs fewer high-impact Western consumers being born, and campaigns for it. It’s why, for instance, we produced and regularly share the graphic below. Economic development is the right of those currently living in poverty, and the only way a finite planet can cope with the strain is for the rich to consume less of its resources – by moderating their behaviour and reducing their own numbers.

Had Dominic Lawson chosen to look at Population Matters’ website, he would certainly have found that point being repeatedly made.

But this is not only about the rich. If the price of arguing for sustainable populations in poorer countries is hostility and criticism, population advocates must bear it. Reducing and eventually reversing population growth through ethical, empowering, voluntary means helps us all.

Population challenges everywhere

Smaller families help people escape poverty – a fact not lost on the hundreds of millions of people in the developing world who embrace family planning, or many of their political leaders, their demographic experts and representatives of the Global South in international institutions. It’s one that the 200 million women in some of the world’s poorest countries who have an unmet need for contraception are acutely aware of.

While the urgency (especially with regard to climate change) is for fewer new rich people, ignoring those currently poor is short-sighted and dangerous.

First, where demand for resources is high and supply limited, local environmental destruction can be the result, as forests are cleared for firewood, fishing stocks decimated for food and soils eroded by livestock. Those impacts eventually make things worse for people who can no longer rely on the land that used to sustain them.

Second, where developing countries do improve their overall economic situations, their citizens will increase both their levels of consumption and their life-spans. That means a greater environmental impact over a longer period for each individual. Smaller families and slower population growth in developing countries – where birth rates can be double or triple those in the rich world – is therefore also vital to prevent environmental crisis in the decades ahead.

To achieve a sustainable population, people everywhere must have smaller families.

What we want

It’s hard to conceive of a more damning insinuation than “eugenics dressed up as environmentalism”. That Dominic Lawson feels free to make it without taking any effort to find out whether it’s true is a worrying sign of how poisonous and shallow the debate about population can be. It is undeniably true that the history of population concern has included some dark episodes, that population concern advocates have not always been right about everything and that some have used loose and counterproductive language or arguments at times. But to exploit and obsess over those errors in order to condemn an entire argument, and those who make it, does rational debate a deep disservice.

Population advocates want – and work towards – the same thing as every decent, rational person: a global community in which everyone can live better lives, on a healthy planet that can sustain all the life upon it for all the generations to follow. We are guided by compassion, reason and deep concern for human beings, other species and our future. Our argument is simple and self-evident to anyone who looks clear-sightedly at the issues, our values are those of good people everywhere, and the solutions we propose are humane, just and achievable.

Little wonder that support for our cause is growing.

Take action

Find out how you can support Population Matters.